In March, Truckee-based Mountain Hardware and Sports was up against the toughest test of its 43-year record of no layoffs. As the economy was going into a deep freeze, company president Doug Wright sent a letter to his staff on March 17. “It essentially said, ‘I’m going to do everything in my power to keep you guys 100 percent healthy and safe and financially whole,’” says Wright. “They know I’m serious about that.”

He could make that commitment in part because of who owns the business: an employee stock ownership plan, or ESOP. In 2000, its three founding owners were in their early 50s and thinking about their exit strategies, and none of their children wanted to take over.

So a financial adviser suggested a way to keep their legacy going: a gradual sale to company employees. In 2001, the owners loaned money to the ESOP — which is a trust, a separate legal entity run on behalf of the employees — to buy about half the company shares. In turn, the ESOP distributed those shares to employees who’d been with the company long enough to qualify. (Mountain Hardware employees begin receiving stock after 1,000 hours of service and become fully vested after six years.)

By 2013, the ESOP had bought out the founders completely.

Employee ownership is part of why the company prioritizes keeping staff. Wright says the company had enough money in reserve in late March to keep going for a few months, which it used to retain employees. The company has a governance structure much like that of any other — as president, he reports to a board and is responsible for performance. What makes the business unique is who owns it. “I don’t have a shareholder (who’s) saying, ‘Look, if I don’t get a 15 percent return every year in the form of a dividend or something, I’m going to be disappointed,’” says Wright.

“I don’t have a shareholder (who’s) saying, ‘Look, if I don’t get a 15 percent return every year in the form of a dividend or something, I’m going to be disappointed.’”

Doug Wright President, Mountain Hardware and Sports

So in March, when the governor recommended that those older than 65 stay at home, Mountain Hardware furloughed its five older staff who were affected but paid their salaries. “That’s the beauty of the ESOP — our staff is supportive of that,” says Wright.

Thirty-two companies in the Capital Region have such ESOPs, according to the most recent available data from The ESOP Association, a national group that advocates for employee ownership. ESOPs let employees own a piece of the company and are a way for the wave of retiring CEOs to leave a legacy for their employees and keep their companies under local control. Research indicates that employee ownership can transform company culture for the good and improve profit margins. But the effects of an ESOP sale on the final price and extra transaction costs mean they’re not the right choice for every seller. And at least one worker-advocacy group contends they can sometimes put employees at financial risk.

ESOPs are essentially retirement plans, though most companies with an ESOP also offer a secondary plan like a 401(k), according to one survey. Owners sell their shares, or a portion of them, to the ESOP, which holds them on behalf of workers. Usually, the company or the ESOP gets a bank loan to finance the sale. In other cases, selling owners make the loan themselves, deferring their payout on the sale. In the years after the transaction, the company uses part of its profits to pay back the loan and distributes remaining profits to the ESOP in the form of stock, which, in turn, is paid into employees’ accounts. When workers leave or retire, they can cash out those shares.

‘What’s Most Important to Us?’

Many local economies are about to see thousands of leader years of experience evaporate as baby-boomer owners retire. By 2030, all boomers will be at least 65. That generation owns nearly half of the country’s privately held businesses with employees, according to an estimate based on the 2012 Census Survey of Business Owners and Self-Employed Persons by Project Equity, a nonprofit that promotes employee ownership.

Many retiring leaders don’t have an exit strategy. A 2019 survey by the Wilmington Trust, a financial advisory firm, found that just 55 percent of boomer owners have a formal business succession plan. In this economy, many of those companies could shutter if they don’t find a buyer.

Stephen Bender is one of the exiting boomers. About 15 years ago, he was in his mid-50s and starting to strategize how to pass on ownership as the second-generation CEO of Bender Insurance Solutions in Roseville. (He’s also a member of Comstock’s Editorial Advisory Board.)

A new generation was coming up through the company, with three of his daughters and a nephew working there. Maggie Bender-Johnson joined the business in 2005 and worked her way up from account executive to president by 2018. Jillian Bender-Cormier, brand manager, joined in 2008, and Alison Bender, account executive, in 2011. Chris Bender, the nephew, came on in 1996 and is vice president of benefits.

By 2017, as CEO, Bender was ready to sell his stake as majority shareholder. He wanted to turn his shares over to that rising generation, but there was a problem. How does a majority shareholder get a fair price for growing the company while making the numbers work for those younger leaders? Those executives are usually in their prime earning years, but it’s difficult for them to buy out a majority shareholder in a company worth millions of dollars with payments over a short period. The math doesn’t add up.

The alternative was for Bender and the rest of the ownership group to sell to an external buyer. The insurance industry is consolidating fast: In 2018, there were more than 600 insurance mergers and acquisitions in the U.S. and Canada, a record. But selling a company that’s been owned locally since 1938 to an outside buyer could have big downsides, including possible layoffs, which often accompany mergers and acquisitions.

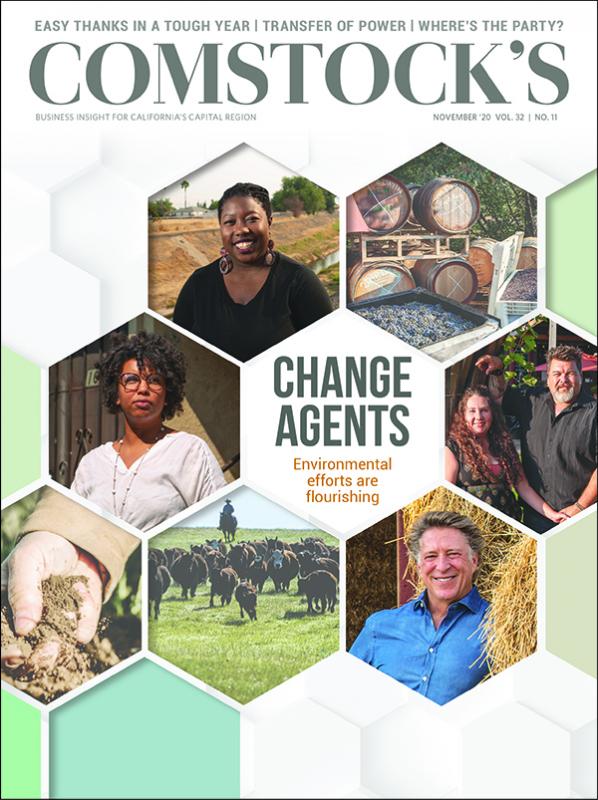

John Riina assists a customer at Mountain Hardware and Sports in

Truckee. The employee-owned company added 22 employees when it

opened a second store in Truckee on July 1.

Bender Insurance Solutions’ board of directors discussed forming an ESOP as a solution but were skeptical. Bender-Johnson was “not a huge fan,” she says, fearing employee ownership would mean losing operating control of the company. She knew of an insurance company in the Bay Area that used an ESOP to let a retiring owner cash out all at once, and that created a huge debt load for that firm.

So Bender-Johnson spent 18 months learning all she could about ESOPs. She talked to local employee-owned companies like Tesco Controls. She attended a national ESOP conference, making friends with leaders of insurance companies that had one. She met with an attorney who specializes in ESOPs and put together a feasibility study.

That projection showed that shareholders would make a big financial sacrifice in an internal sale via an ESOP. In an external sale, the price is whatever the market will bear, and strategic buyers — those in the same industry looking to capture market share through a merger or acquisition — are willing to pay a premium. By contrast, in an ESOP sale, an independent appraiser sets the purchase price. In Bender Insurance Solutions’ case, if the ownership group decided to sell to a strategic buyer, they could have received three times more than in an ESOP sale, Bender-Johnson estimates.

There were other costs that came with an employee sale. They would need to hire an external trustee to run the ESOP, and they would have to pay $30,000 for the trustee’s attorney plus $30,000 for their own attorney. The expense and the partial loss of control to a trustee gave Bender second thoughts.

Ultimately, what kept the company from giving in to an outside acquisition was its history in the community. “The ownership group had to dig deep and say ‘What’s most important to us here?’” says Bender-Johnson. “If it’s really important for us to get stinking rich, then let’s just do it. But because we have an 80-plus-year legacy, to us, it was worth so much more than just money. So we were open to a lower deal.”

The company went through with it, and Bender Insurance Solutions became employee owned on Nov. 1, 2018.

Tallying the Tradeoffs

Bender Insurance Solutions’ story skips over one key advantage of employee ownership: huge tax breaks. Selling owners can defer or avoid paying federal capital gains taxes on the sale — the top rate is 20 percent now — if they reinvest in U.S. corporate stocks and bonds within 12 months and meet a few other conditions.

For companies that are S corporations, those for which business income or loss passes through to the shareholders’ tax returns, the tax incentive is even bigger: The portion of the business owned by the ESOP is completely exempt from federal income tax. So if an S corporation ESOP owns 60 percent of a company, it pays no federal tax on 60 percent of its income.

Those tax subsidies have to be weighed against the possible sales discount and extra transaction costs. But there are other downsides to consider. For example, the federal government’s treatment of ESOP sales has made them more of a legal risk than they need to be, according to Patrick Mirza of The ESOP Association. Other ESOP proponents agree. By law, an ESOP can’t pay the seller more than the company is worth. But no federal regulation precisely defines the process that an independent appraiser must use to determine fair value. Instead, the government has sued many appraisers for valuing a company too high at the time of the ESOP sale, and in at least one case sued the selling owner for choosing an appraiser who had a conflict of interest.

And the news isn’t all good for employees either, according to a report from the Washington, D.C.-based Pension Rights Center. Those who are laid off can cash out their shares, but ESOPs have the right to change their rules to delay making those payouts for up to five years to ease a cash crunch. That timing could spell disaster; employees are most likely to need money immediately following a layoff. Worse, if the company is struggling, the value of employee shares is likely to be lower when they do get their payout. At RadioShack and Enron, both of which had ESOPs, workers lost most of their retirement savings in such company collapses.

Will Culture Help in a Downturn?

Bender-Johnson says she’s seeing positive effects of employee ownership on firm culture after just two years. Since it went into place, staff are more likely to identify areas where they might trim — they call it “ESOP waste.” Bender-Johnson points to a small change: The team decided to stop making coffee toward the end of day to avoid dumping a full container of unwanted coffee. Wright has long seen that mentality at Mountain Hardware and Sports, where employees regularly check up on each other’s performance because they know it affects their own retirement money.

But experts say an ESOP doesn’t change company culture by itself; firms must educate staff about employee ownership. Bender-Johnson says it’s important for staff to see the impact of company performance on their personal finances. So they’ve invested in an ESOP marketing platform that, among other features, gives staff access to an ESOP calculator that uses the company’s growth rate, personal financial information and other data to calculate their retirement outlook.

Mountain Hardware and Sports has an employee-run ESOP committee that keeps up to date on the company’s performance, and the committee members are paid for that time. The committee organizes ESOP educational events three times a year, and at least once a year someone on the committee sits down with every employee to explain how the ESOP works and where the company stands financially.

That’s essential to getting employee ownership across because “ESOPs are complex as heck,” says Wright. That educational investment also saves the company money on turnover. Retail stores nationally lose an average of 60 percent of their employees each year. But at Mountain Hardware, 45 of the company’s roughly 90 employees have been with the company at least six years.

Proponents of employee ownership say loyalty like that happens when staff buys into the company mission. In turn, that may be why ESOP companies have weathered downturns better than others, according to at least two studies.

Companies with ESOPs hope those patterns hold this year. Not only has Mountain Hardware not laid anyone off — it added 22 positions after opening a second store in Truckee on July 1, a move that had been planned before the state stay-at-home order in March. Still, Wright is quick to note that the state’s declaring hardware stores essential businesses has to some degree immunized the company from the pain that companies not declared essential haven’t been able to avoid.

The day before California’s order took effect, Mountain Hardware staff took to the company truck to make deliveries — a thermometer to one customer, a blender to another — and the store waived the delivery fees. Wright says he doesn’t need to motivate his employee-owners to make extra effort during the crisis. “They aren’t going, ‘Why do we have to do this?’ They’re saying, ‘Hey, whatever we gotta do.’ When people can be part of the decision process, if you allow that in an ESOP, it’s like a rocket (booster, and that) makes a huge difference in how people do their jobs … and the success of the business,” he says.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Minding the Family Business

Why family-run companies can be better poised to navigate hard economic times

While large companies often have shareholders and untold numbers of employees to satisfy, family businesses can maneuver more deftly and swiftly, powering through as best they can.

The Buy-In

It was sometime in 2004 when Larry Booth and his brother Martin swallowed the truth that they wouldn’t live forever.

Rx for Merger Madness

Hospitals and physician practices are consolidating; for businesses covering their workers, that means re-evaluating current plans to keep health care costs from soaring

In the 2019 American economy, the big are getting bigger. Mergers are everywhere — the number of mergers and acquisitions exceeded 15,000 in 2017, a record for a single year, with 2018 a close second.

Merger Beware

Due diligence for buying and selling in today's market

Buy enough businesses and eventually you learn what to expect from the process.