When lightning sparked fires in the Sierra Nevada mountain range before European settlement in the 1850s, they were left to burn, naturally clearing out trees, shrubs and grasses. “Certainly in California, in fact in much of the Western United States, any of the dry forests historically had [natural] fire regimes in which they used to burn every 10 to 20 years roughly,” says Malcolm North, a research scientist with the U.S. Forest Service and an affiliate professor of forest ecology at UC Davis. Early historians of California wrote about the smoky smell in the air through summer.

Native Americans relied on fire for things like herding animals for a big hunt and creating open space for villages. Cowboys used fire to sustain pastures for grazing. “When the cowboys left higher elevations, they would light behind them as they left — light the mountains or hills on fire,” says Jennifer Hinckley, a fire management specialist formerly with the U.S. Forest Service and now with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Upon returning in the spring, there’d be new grass for cows and sheep to forage.

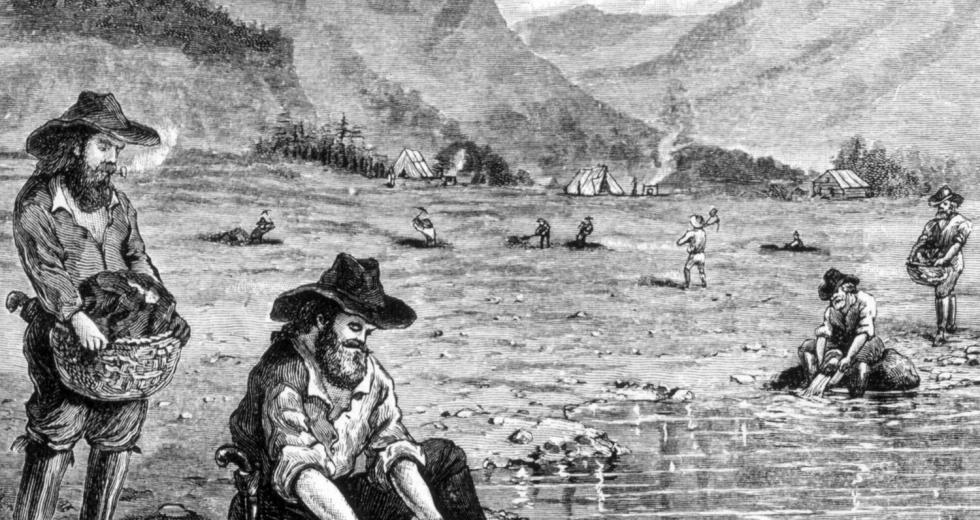

(Photo by Fred Greaves)

Meanwhile, as cities grew overcrowded and polluted in the late 1880s, affluent Americans retreated outdoors for fishing, camping, hiking and bird-watching. Preservationists suggested nature had inherent value, and conservationists argued nature must be conserved for its economic benefit to people. In the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt established 230 million acres of national parks, forests and monuments and oversaw the creation of the Forest Service in 1905.

Then in 1910, forest fires broke out in Montana and tore through the Northern Rocky Mountains in what came to be known as the Great Fire. “The Forest Service actually managed to save a bunch of towns and people, and it became very clear that in terms of establishing a mission … that fire was going to be one of the things that was going to keep the Forest Service financially alive with politicians in [Washington, D.C.],” North says. “It became a real central focus for the agency itself and has remained so.”

By the 1920s, a shift to fire suppression had taken hold. While some scientists at the time argued that the right kind of fire benefitted forest ecosystems, their voices were overshadowed, North says. Outdoor recreationists didn’t much care for wildfire, and it posed a danger to towns and the emerging commercial timber industry. “A lot of people were saying, ‘Hmm, we could be growing a lot of board feet and more fiber if we got rid of fire,’ ” North says. “That was definitely one of the reasons fire was put out.”

Over the ensuing decades, wildfires continued to be squashed. In the 1960s, Americans grappled with the effects of water and air pollution, which led Congress to pass legislation that further restricted the use of fire as a tool. By the 1990s, what had become a flourishing timber industry was about to enter a period of conflict and consolidation that would set up some of the conditions — and challenges — California faces today in effectively managing its forests.

Recommended For You

Beating the Burn

California’s plan to deal with deadly and devastating wildfires — including controlled burns, thinning and a restoration economy — is ambitious; is the state up to the task?

Past approaches to forest fires have been a misinformed regime of fire suppression: extinguishing all flames quickly. Now California’s forests are overgrown tinderboxes-in-waiting; the approach is changing, but there’s a lot of work to do.