Tucked between subdivisions, strip malls and office complexes, in and around the metropolitan sprawl of Sacramento, horses and their owners are quietly making their mark in the business community. From Twinkle Gorman’s paddock on Fair Oaks Boulevard to Ann Taylor’s booming breeding business at the Woodland Stallion Station and countless boarding and training operations up and down Auburn-Folsom Road, equestrian businesses are riding a good economy, making money and having fun.

For show and profit

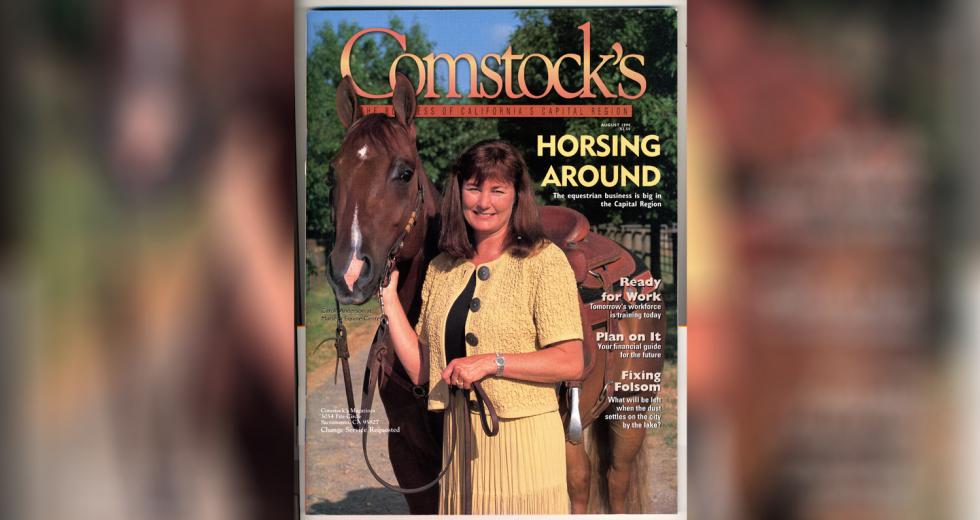

“I think people would be amazed if they knew how many jobs there are locally in the horse business,” says Carol Anderson, president of Murieta Equine Complex (MEC). According to the American Horse Council, a total of 124,400 people in California make their living breeding, raising, showing, racing or training in what has become a $112 billion business nationwide. “There are actually more horses per person in Sacramento County than in any other California county,” Anderson says as she looks out over the expanse of horse stables, show rings and pastures that bring literally thousands of people each year to Rancho Murieta for a wide variety of events from local pony clubs to internationally recognized dressage competition and everything in between.

About fifteen years ago, Carol’s father, Pacific Coast Building Products founder and professional sports entrepreneur, the late Fred Anderson, acquired the equestrian facility near Rancho Murieta. It was Carol, however, who took so naturally to riding and showing that he handed the management of MEC to her.

“We are well set up for both show horse people and spectators,” says MEC Vice President and General Manager Kelly Bess. “We have over 40 events a year and they include breed shows for Paints, Appaloosas, Morgans, Quarter Horses and Arabians. We also have dressage, combined training, hunter/jumper, reining, cutting, roping and rodeo.” The biggest spectacles are the rodeos and bull riding events. The spring Arabian Horse Show and the Western Futurity Spectacular alone draw between 350 and 450 horses each.

Three years ago, Anderson built a 60,000 square foot indoor ring with seating for 3,000 at a price of more than $500,000. “It was a major investment,” says Bess, “but we needed a facility more conducive to both exhibitors and spectators.” They got it. With the new building, MEC is able to attract bigger events. “Dressage and reining are probably the two fastest-growing events,” Bess guesses. At a reining event in September, more than $92,000 in awards will be given out. Entry fees for these events range from $100 for schools to $1,000 for recognized shows. The rewards range from confidence-building that children get from working hard and competing to the value added to a winning horse’s selling price plus the tens of thousands of dollars in prize money and purses at national championship events. Many times, MEC hosts events to benefit local charities like Big Brothers/Big Sisters. Because of the indoor facility, MEC can host events year around.

Although Bess is paralyzed from the waist down, he handles everything from arranging show schedules to jumping on a horse, with the aid of a very special saddle, and riding to the far reaches of the center to take care of business. And he attributes the growth in popularity of sport horses to the improvement in the economy. “Money is coming back to the horse industry. You can see it everywhere. Our events are up.”

Thrown for a loop

The scenario was not always so rosy. Ann Taylor, who has owned the Woodland Stallion Station for 15 years and was involved with horses 15 years before that, remembers when a change in the tax law in 1988 really crippled the horse breeding industry. “All incentives for investments went out and horses were just dumped on the market,” she recalls. Lawyers and doctors who had purchased breeding horses for tax write-offs and toys for their children could no longer be recreational owners and still get a tax break.

“Things are warming up again with the increased discretionary income,” says Taylor, who boards, trains and breeds some of the top horses in the nation on her ranch in Yolo County, “but people are not in this business to get rich; they are in it because they are horse crazy.”

She points to the high cost of breed- ing, feeding and caring for horses balanced against the enormous odds of selling an award-winning yearling. The breeding project starts with stud fees that range from $300 to $30,000 and up, depending on a stallion’s credentials. That is not including $250 to UC Davis for veterinary work and $9-a-day board for 30 days. If the breeding is successful, that mare will have to be fed at a mini- mum of $600-a-year during the 11 month gestation period. Once the baby is born, three years of food and board at about $1,800, miscellaneous shoeing and veterinary work, around $2,100 in training and a lot of emotions have been invested for a total of over $7,000. If that breeder is lucky, the horse will fetch about $4,500 for a net loss of $2,500! There are exceptions, of course. If the horse can be sold as a yearling, Taylor estimates the breeder can make a profit of about 10 to 15 percent.

European enterprise

So who is making money? Taylor and Anderson point to the trainers as one of the beneficiaries. Swiss-born horseman Rudy Leone who moved to the United States about 25 years ago “for a year, to get some experience,” has also witnessed the ups and downs in the industry and shifted to the teaching end of the reins.

Over the years, Leone has operated several different equestrian operations. “When sales were hot, I did sales,” he says. “Sometimes I’d sell 300 horses in a year. When the dollar was strong in Europe, there was a big market for imported horses. Anytime the economy slows, leisure activities, like horse sports, decline. Right now, however, there is a big demand for riding lessons and training,” Leone says. “The horse business is better than it has been in a long time. All aspects of it.

In addition to training and sales, Leone decided to implement a breeding program. Accustomed to the systematic European ap- proach to tracking bloodlines, Leone was dismayed at the lack of records for American sport horses. While the Jockey Club extensively tracks racing thoroughbreds, it does not track thoroughbreds that enter the horse show world. “Over 150 years worth of records are available in Europe and the breeders and associations work together. They track the progeny in every discipline, not just if they win. Every time a horse shows, it is recorded.”

In 1983, Leone formed a partnership and through timing, contacts and a little luck, imported the beautiful bay stallion, Telstar, a Dutch warmblood who had proven himself in Europe. “I felt America needed better bloodlines and the groundwork had already been done in Europe.” Leone found that Americans have a different attitude toward breeding. “Americans want instant reward — to make that first generation a superstar. Sometimes you have to breed several generations for a superstar and Americans just aren’t that patient,” Leone laments. The costs associated with marketing a stallion, and the upkeep on mares adds up. Although the Telstar Partnership never made a profit from breeding, they made up for their losses with the sale of Telstar’s offspring. Many went on to become champions in their own right.

When asked about his life in the horse business, Leone laughs and says, “It is a tough, hard business. You have to stay educated, but if I had my life to live over again, I wouldn’t change a thing!” What is changing in the million dollar horse industry is the outlook for the future. Ann Taylor hopes more young people will get involved with the sport because it is character-building for them and good to have fresh blood — both human and equestrian. With more than 80,000 horses estimated to be in the greater Sacramento area, it looks like people of all ages are climbing on the back of the horse industry for profit and fun.

Recommended For You

Still Going Strong: Catching Up with C.C. Myers

C.C. Myers was lauded for “working miracles in heavy construction.” A project in Santa Monica brought Myers and his company worldwide recognition and many honors and awards as well as a spot on the cover of the July 1995 issue of Comstock’s magazine.