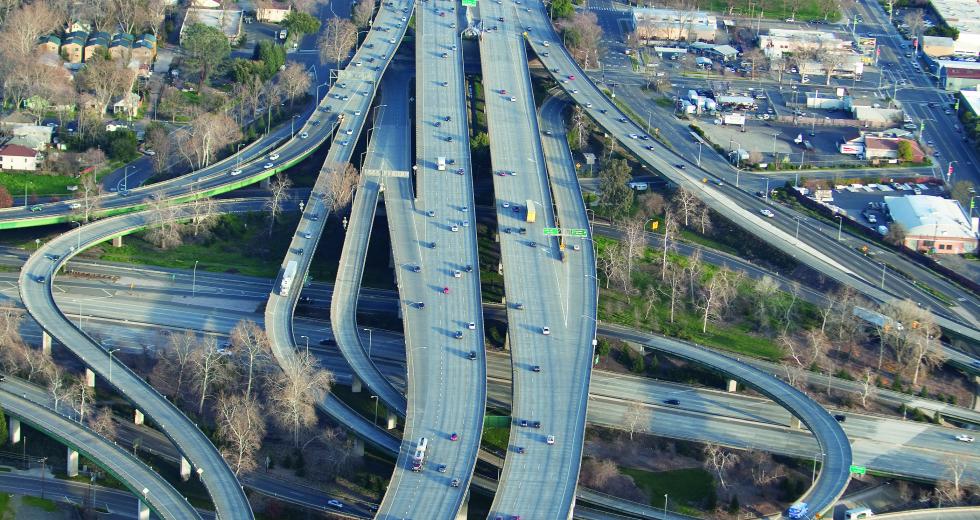

It’s no secret that city leaders have cut jobs, programs and services as quickly and responsibly as possible in response to economic malaise. But the numbers still fall short of filling growing budget gaps in jurisdictions across the region. And as the capacity or desire to borrow dwindles, many municipal projects are delayed or scrapped all together. City leaders say they don’t yet know what this year’s cuts will bring, but many agree it’s likely to get worse.

“In a traditional down economy, you have about two years of decreased revenue, but you can typically dip into reserves without a major crisis,” says Gus Vina, assistant city manager for the city of Sacramento. “You get reduction scenarios from each department and make cuts, and for the first two years that’s how we did it. But the cuts are now so deep that some of our departments are running at 50 percent.”

The city of Sacramento’s fiscal year began with a $450 million budget, but because of decreases in property, sales and utility taxes, it has dropped to less than $400 million, making for a $35 million to $40 million shortfall for fiscal 2011.

The situation is no different in Folsom, where the city’s unrestricted reserve fund could dip below 9 percent of the budget this year. Woodland has shed 69 of 380 staff positions in the past two years and is anticipating dropping another two dozen this year; Elk Grove and Stockton have furlough programs in place.

“We’re in the squeezing-the-blood-from-the-turnip phase because there’s no more low-hanging fruit,” says Folsom City Manager Kerry Miller. “The best case for next year would be maintaining status quo.”

To do that, jurisdictions are cutting spending, holding off on capital improvements and trying to bring in additional revenue. Even so, some cities still have major budget shortfalls on top of continued municipal needs and an inability or unwillingness to borrow, even at a time when the bond market is beckoning.

Last October, municipal bond markets were offering their lowest interest rates in recent memory. Markets rebounded shortly thereafter, but long-term bond rates, especially for higher-grade credits, remain attractive. There is strong market access with reasonable interest rates for jurisdictions with lower bond ratings as well.

“We are now hearing across the board that public agencies are getting much more favorable construction bids,” says Piper Jaffray Managing Director Mark Curran. “However, many local governments are seeing their budgets pinched, and even if they could afford to borrow, they are very cautious about borrowing until they see their revenue base turning around a bit.”

The City of Sacramento is one such jurisdiction.

“You have to look at your capacity to borrow, and we’re done,” Vina says. “The financial picture is too tight. But we’re making our payments on the bonds we’ve already issued.”

Still, even if they wanted to, a number of other Capital Region jurisdictions are out of luck.

“Vallejo right now has no access to capital. They could not borrow money at any rate,” says Craig Hill, a principal with San Rafael-based Northcross, Hill & Ach Inc., a financial consultant for public agencies. “Stockton failed at entering the market last year after a City Council member publicly mentioned the city’s option of filing for bankruptcy. That speculative statement was enough to scare off potential lenders.”

Still, not every jurisdiction is beyond consideration. Folsom saw all of its bond ratings — redevelopment, water and general obligation — upgraded from AA- to AA last year, giving Folsom the highest bond rating in Sacramento County and among the top ratings in the state. The city of Auburn is also well rated, having secured an A- for redevelopment agency funding in 2008 and an AA- rating for sewer project bonds in 2009.

“The best case for next year would be maintaining status quo.”

Kerry Miller, city manager, Folsom

In October, Folsom issued a $16 million bond, $8.4 million of which is now being used on a Sutter Street redevelopment and beautification project. The city is not anticipating issuing additional bonds in 2010, largely because most of its capital improvements were already funded.

“We are also seeing high-quality sewer projects locking in long-term interest rates under 5 percent, which is very attractive,” Curran says. “If a community has an important project, we are proceeding with those — we just did financing in Truckee for community improvements. And for other types of municipal projects like expanding city halls and sewer upgrades, I think there will continue to be a strong demand.”

Woodland is coping with the burden of aging infrastructure. Water and wastewater systems are nearing their centennial in some areas of the city. To fund the necessary upgrades, payers will see four 20-percent rate increases in the next three years, and the city, which had a AA- rating in its last round of bond issuance, will likely seek a $9 million bond this year.

Elk Grove needs to build a household hazardous waste facility, according to Katy Baumback, the city’s budget manager. The city has not decided whether to move forward with the project this year, but if it does, a bond issue is sure to follow.

Otherwise, most projects that are not mandatory will have to wait.

“We’ve cut a lot of projects, and others we have simply moved out in our 10-year plan,” says Woodland City Manager Mark Deven. The city has cut parks and recreation rehabilitation plans and has delayed a library expansion and restorative work on the city’s historic opera house.

Developer impact fees, which are down 70 percent, fund most of the city’s capital projects, Deven says. Meanwhile, Measure E funds, which are drawn from sales tax and pay for projects such as road repair and park rehab, are down 23 percent.

For the next three years, the city of Sacramento is looking to right the organization by asking what services it can afford to provide. Vina says he recognizes that the currently high standards of service will suffer.

“The nut we have to crack is $40 million, and to do that we need a complete review of services,” Vina says. “Things that fall below the priority line need to go. The goal here is to reduce the number of employees. I don’t know another way to say it. We can’t afford the number of people we have today.”

Sacramento is anticipating cutting 400 to 450 positions, or about 10 percent of its staff. It will also begin contracting out for services, rather than relying on unions.

“If someone can provide the service and give the community what it demands for less, then we have to go with that,” Vina says. “The unions oppose that … and I know this is going to be dicey, but [they] need to understand the situation we’re in. It’s a sign of the times, and we definitely are not the only city looking to consolidate and contract out. This is not good news for any of us.”

In Sacramento, Folsom and elsewhere, city and county officials are now looking to cut costs by sharing employees and consolidating programs and services.

In January, Woodland launched Web-based surveys to poll residents about where they would be willing to see cuts made and which programs and services they find most valuable. City leaders are also hosting focus groups and stakeholder interviews to determine city service priorities.

Meanwhile, more silver lining shines in Folsom where assessed property values and property tax revenues continue to increase. Folsom has also experienced the lowest sales tax decline of any city in Sacramento County — about 10 percent.

Neighboring Roseville and Elk Grove are down 20 and 29 percent, respectively, in the past two years.

At the same time, a number of private-sector projects have come on line in Folsom, bolstering sales tax revenue. The Palladio shopping center opened its first phase in December, adding a few hundred thousand dollars to tax rolls right off the bat.

“If we lost our gas tax, we would have to seriously consider measures â?¨like not operating street lights.” —Mark Deven, city manager, Woodland

Auburn is in a similarly healthy situation because it didn’t participate in large-scale residential development. Because the city didn’t become reliant on developer fees, it hasn’t been hurt by the lack of them. The same is true for sales tax, which has also remained stable since Auburn residents have historically shopped for groceries and daily needs close to home but spent disposable income on restaurants and retail outside the city’s limits.

Still, leaders in Auburn, Folsom and other cities across the region are watching the headlines and hoping for economic stability.

“If more bad news hits — if the bottom falls out of the commercial real estate market, for example — cuts could be draconian,” Vina says. The word amputate has even been thrown around the Sacramento offices.

With vocabulary like that, it seems logical that a number of jurisdictions have rallied behind the League of Cities and its Local Taxpayer, Public Safety and Transportation Protection Act, scheduled for the November 2010 ballot.

The initiative would prohibit the state from taking, borrowing or redirecting local taxpayer funds dedicated to public safety, emergency response and other vital local government services.

Money borrowing from the state has been painful for cities such as Woodland, which relinquished $800,000 in redevelopment funds and $1.34 million in tax revenue. As such, the city is endorsing the ballot initiative, as it is concerned that the state could poach other crucial funds, such as gas tax revenue that equates to $1 million a year for the city.

“If we lost our gas tax, we would have to seriously consider measures like not operating street lights,” Deven says.

So far, most Capital Region jurisdictions have not had to resort to such extreme measures, but until the economy shows significant long-term gains, no one is out of the woods. Vina and other city leaders say it’s too soon to tell how deeply programs and services will be hampered over the next fiscal year, but that residents should start adjusting to the fact that the current quality and speed of municipal services is likely to decline.

“Sometimes these cycles are good for organizations,” Miller says. “A lot of things we’ve trimmed will probably remain after we’ve improved, probably because we’re discovering ways to do it better.”

Recommended For You

The Auburn Advantage

How one city turned lifestyle into business leads

Downtown Auburn has a distinct, modern-day Mayberry feel, from the stone-paved sidewalks to the rustic brick bus stop. But five miles away,

Folsom City Blueprint

A city manager plans for the future

California’s ongoing economic slump has been historically challenging to local governments, even in relatively affluent areas like Folsom, which has one of the highest per capita incomes in the Capital Region. We sat down recently with Folsom City Manager Kerry Miller to discuss the city’s current fiscal condition and plans it has to thrive as the economy improves.