When Kevin Marshall co-founded a real estate valuation firm in 2001, his first order of business was to bust down the walls.

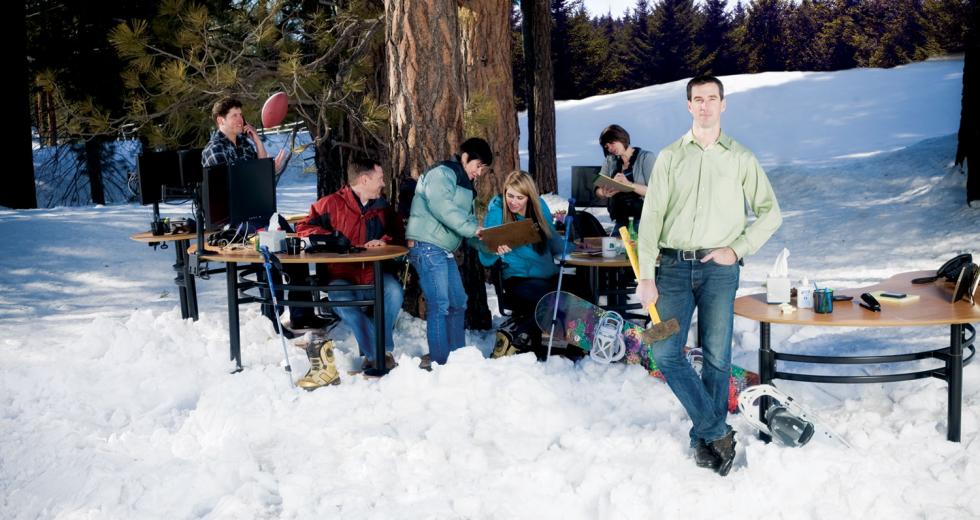

Not just the kind that separate buildings into rooms. He wanted to tear down any obstruction that he says could block creative thinking: cubicles, dress codes, gray carpet, fake plants. You won’t find any of that stuff in the company’s three office buildings, huddled in the snow-covered slopes of Truckee, Calif. “Cubicles are great,” Marshall says, “for hiding people from each other.”

Instead, employees work at kidney bean-shaped wooden desks. Natural light streams through windows, reaching out to real plants that need water to survive. Workers can wear whatever they want, and there’s not a cubicle in sight. It’s on this foundation that ClearCapital.com Inc. established its business model as a real estate valuation and risk-assessment data and solutions provider for big financial services companies. And in the past decade, as the economy buckled and the housing market snapped, this company has seen explosive growth. In 2006, Inc. magazine ranked Clear Capital No. 30 on its list of the fastest-growing private companies in the country. Last year, the business pulled in $113 million in revenue.

For Marshall and his co-founder, CEO Duane Andrews, success has nothing to do with numbers. Indeed, the company provides analytics, market data, condition inspections and valuations on residential and commercial real estate as they work with a national network of more than 40,000 agents, brokers and appraisers. But they say the company’s expansion to 50 states and beyond validates Clear Capital’s core belief in the value of people, not property.

“That’s where a business flourishes,” Marshall says. “We’re not just a bunch of people exchanging PDFs back and forth. We want to foster a sense of community.”

In the Sierra, the town of Truckee is known for two things: year-round vacations and its historic ties to the Donner Party, who were trapped in the mountains by heavy snowfall and allegedly resorted to cannibalism.

For the past 30 years, construction and resort development have driven business in Truckee. Half of the 12,000 housing units are vacation homes, but the industry took a beating in mid-2007. “We went from permitting about 300 housing units a year to about 30,” says Tony Lashbrook, Truckee’s town manager. “We’re a real town, but we’re also a resort town. When we lose a large percentage of jobs, that balance is at risk.”

Granted, Truckee might not be thought of as a go-to place to launch a tech company. But in the digital age, where people can conduct business from anywhere with a computer and an Internet connection, Marshall and Andrews decided to set up shop in a community with a small-town vibe that could mirror the business culture they wanted to create. The relationship turned out to be mutually beneficial. As the construction and tourism industries waned, Clear Capital continued to grow and fill some of the employment gaps. And the company also contributes to the community through volunteer service, the support of sports teams and donations to local nonprofits.

“We’re very fortunate here, especially in these challenging times, to have an anchor like that in Truckee,” says Tom Watson, commercial real estate broker at Truckee River Associates. “The people that work at Clear Capital are starting to contribute to the community in their own way. In a small community like this, that’s huge.”

Marshall has never been the big-city type anyway. He grew up on a 5-acre farm in Newcastle. He got a dose of technology one Christmas in the late ’70s, when his dad gave him and his brother an Atari 2600. His dad modified the console to play Intellivision and bootlegged Atari games loaded on small computer chips. Looking back now, he says jokingly, it kind of seemed illegal. “But that’s when I realized that people control technology, and you don’t have to be trapped into only what you pull out of the box at Christmastime.”

In his basement, Marshall built models, such as airplanes and cars, and worked alongside his dad with vintage TV tube-testing equipment, oscilloscopes and pretty much anything you could plug into a wall in the ’70s and ’80s. His father had them build their own lamps and extension cords, rebuild car engines and fix their toys, rather than buy new ones.

Nathan Oates, pastor of the Emmaus Church Community in Lincoln, grew up with Marshall and remembers those days. “He was always tinkering with things,” Oates says. “One of the things that used to frustrate me is that he was so committed to everything being excellent.”

Marshall, he says, didn’t watch much TV. The entrepreneurial bug bit him in the mid-1980s when he turned a $1,000 profit selling a pig for 4-H Club, the USDA’s youth organization. But he liked skateboarding more than math class. In his sophomore year, his parents split up. By his senior year, he had changed high schools, moved out of the house with his parents’ blessing and began living with a mentor. It was a tough season, but he emerged stronger than before, due to his foundation of faith.

“This focus on co-workers’ well-being fosters a much better environment and management training than the typical dog-eat-dog approach to business.”

Kevin Marshall, president and co-founder, ClearCapital.com Inc.

“He could have become really self-focused,” Oates says. “Instead, he came out of that experience wanting to help other people. We always talked about helping kids feel like they’re important and treating them with love and grace and appreciation. He’s taken that same ethic and put it into his customer service.”

By the dot-com era, Marshall had gotten into programming, producing Internet-based applications, and held several technology management positions. He led projects to convert paper products and client server applications to Web-based apps. When he met Andrews, the two of them decided to go into business together. In 2000, they co-founded REONetwork.com, a database of real estate-owned vendors, which connected them to banks and loan servicers nationwide.

They bought servers and networking equipment on eBay from defunct tech companies. In noticing opportunities in broker price opinions, they saw a place to expand the business and provide Web-based software. They flew all over the country, pitching the idea. At that time, software as a service wasn’t widespread, Marshall says, and customers couldn’t wrap their heads around the concept. Marshall and Andrews met at a Denny’s in Garland, Texas, to discuss the fate of their company over $2.99 Grand Slams. “We weren’t sure if this business was going to fly,” he says. “We had no outside investment. It was just us. We had to change the business model.”

By 2004, the company had changed its model from a tech company to a valuations company and changed its name from BPOTracker.com to ClearCapital.com. The company now claims 35,600 square feet in Truckee’s Pioneer Commerce Center, a redevelopment born from an abandoned construction junkyard, along with 9,000 square feet in Roseville and a New York City office. Clear Capital has about 300 employees from all over, and Marshall has no plans of braking.

“He’s kind of a poster child for a long-standing town notion that if we focus on maintaining and enhancing the quality of life, then the economic development may take care of itself organically,” Lashbrook says.

And from the look of it, that’s exactly what’s happening. In the wake of Clear Capital’s success, a surge of entrepreneurs with ties to Silicon Valley and the tech industry have flocked to Truckee. The budding tech community inspired Johannes Ziegler to found the Silicon Mountain network after he moved from Palo Alto to Truckee nearly three years ago. He was surprised to meet so many tech folks, commuters as well as fixtures. But, he says, many were scattered around town.

He created the group to network and share ideas at monthly meetings. About 80 people are in the group; about half show up. As the CEO and founder of Always Icecream, a learning and play platform for young girls, Ziegler used to have an office in San Francisco. But people started telecommuting, and the shift freed him to move wherever he wanted. “Everything is Web-based,” he says. “There are some people who say it’s not always easy because there’s not the infrastructure like in the Bay Area. But they’ve tried to make it work because they want to be where they can enjoy the outdoors and nature.”

With that in mind, it becomes clear that the classic real estate mantra has played a vital role in Clear Capital’s evolution. The company’s unlikely location allows employees to experience the best of both work and play worlds. Watson, who leased Marshall and Andrews their first space, remembers them in the early days, sitting in the hallway, mapping out what would become a blueprint for the business. Watson knew he was witnessing the birth of something big.

“A lot of areas bigger than us would love to have that type of tenant here,” he says. “Our goal is to help them nurture their business as best as we can and provide a place in Truckee for their growth.”

On a recent winter morning, Marshall gave a tour of his office. He’s a chipper man with slender build and can strike up a conversation with people he’s never met. In his spare time, he reads history books on the world’s wars, spends time with his family and races fast cars. You can tell he enjoys his job and the people he works with. He doesn’t just know his employees by name, but he can remember where they’re originally from.

“There’s a continuity of integrity here,” says Tim Knight, Clear Capital’s director of product management in the BPO division, who started out as a client before joining the team. “As a company grows, that’s one of the things it loses. But we’re accommodating massive growth, maintaining cultural mores and treating people the same way we did nearly 10 years ago.”

Marshall makes it his business to meet every new employee and has a no-voicemail policy, meaning that any client who calls will speak directly to someone. The company promotes managers based on who makes people around them excel at their jobs. He reminds his staff that every day, they should sit down at their cubicle-free desks, look at a neighbor and make his or her day better.

“You know you’re coming to a place where people are looking out for you, and they want you to be successful,” he says. “Not like Milton in storage room B.”

He’s referring to the film, “Office Space,” the 1999 comedy that satirizes typical white-collar work life and the banality of office politics. It’s one of his favorite movies, and it helped teach him what not to do.

Recommended For You

Own & Leisure

Major resorts change hands in the High Sierra

Spring weather has graced area ski resorts with abundance, dumping generous volumes of snow on the slopes for giddy guests.

Water Under the Bridge

A plan for Squaw Creek is a plan for jobs

Squaw Valley USA was once the premier ski resort of California and the world-renowned site of the 1960 Winter Olympic Games. But in the decades that followed, the resort’s managers focused on the mountain, and Squaw became eclipsed by other resorts that boasted hotel rooms and other amenities to capture business in the dry months.