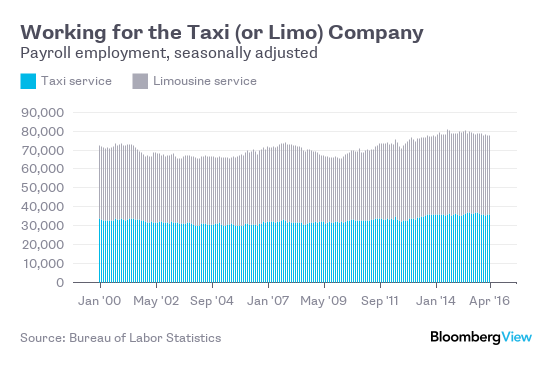

Amid all the gnashing of teeth about the crummy May jobs report, I decided to look into some April jobs numbers. They were released June 3 as well, because the Bureau of Labor Statistics puts out a lot of its industry-level employment data with a one-month delay. The particular industry I was interested in was taxi and limousine services, where employment went from 77,700 in March to 77,600 in April. That April number is likely to be revised next month; the point is that it’s basically unchanged. And it hasn’t changed much for a while.

For a business that’s being disrupted in a big way by the rise of ride-hailing companies Uber and Lyft, this is remarkable. Yes, employment at taxi and limo services declined slightly over the past two years even as overall employment grew — competition is hurting the incumbents. But it hasn’t caused them to collapse, either. At least not yet.

Maybe, I wondered, this evidence from the jobs report could help answer the question of whether Uber and Lyft are mainly replacing existing taxi and limo services or mainly adding to them. This was the core of the Great Uber Valuation Debate of 2014 between New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran and venture capitalist Bill Gurley. If you looked at Uber as a company displacing an existing industry, as Damodaran did, then its valuation — $17 billion then, $62.5 billion now — made no sense. If you looked at it as a company that’s effectively creating a new industry, as Gurley did, then maybe the valuation wasn’t, and isn’t, so crazy.

This question also matters for public policy and public perception regarding the ride-hailing companies: If they’re just taking business from cabs by skirting the regulations that govern taxi service, that’s one thing. If they’re getting lots more people to hail rides rather than drive drunk or take up parking spaces or just stay home, that’s another.

So what does the jobs data tell us? The numbers on employment at taxi and limousine services can only get us so far, because most of the people who make a living taxiing and chauffeuring others around aren’t employees of taxi and limousine services. Some of them work as employees in other sectors: auto dealers, traveler accommodation, motion picture and video industries. The majority, though, are self-employed. The BLS reports data on these drivers too, but only on an annual basis and only since 2010.

Uber, which opened for business in San Francisco in May 2010, only started expanding nationally in 2011. Lyft was founded in 2012. So one takeaway from this chart is that self-employment or independent contracting is not some radical new thing being foisted on drivers by Uber and Lyft — it was already the industry norm in 2010, before they were a factor.

Another is that the number of taxi drivers and chauffeurs has grown a lot since 2013. The ride-hailing companies do appear to be making the overall business bigger — not just replacing the incumbents. What’s more, the numbers in the above chart surely underestimate the actual number of people driving others around for money, by a lot. That’s because most Uber and Lyft drivers are moonlighting. Two-thirds of Uber drivers surveyed in December 2014 had a full-time job other than driving for Uber. If asked in the Current Population Survey — the source of the data behind the gray bars in the above chart — what they did for a living, these people would name that full-time job, not “taxi driver” or “chauffeur.”

Uber says in April that it has 450,000 active drivers in the U.S. If that’s true, and most of those drivers don’t show up in the BLS job count — and I think it’s reasonable to believe both of those things — then the market expansion has been much more dramatic than indicated in the chart.

There are still lots of bad names you can call Uber and/or Lyft if you want. But you really can’t say they’re zero-sum.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners, or of Comstock’s magazine.