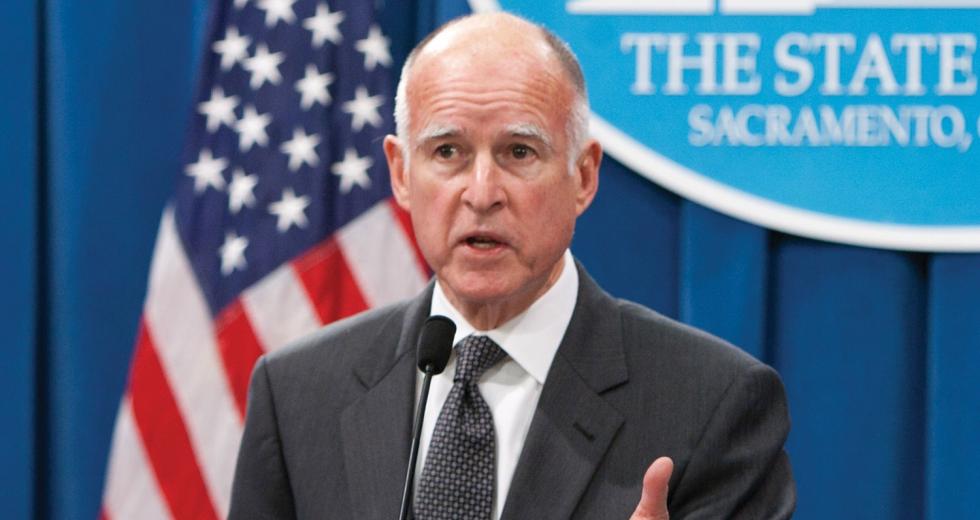

We’ve had several months of the new administration of Gov. Jerry Brown. There are remarkable similarities — and a few notable differences — between the Gov. Brown of 2011 and the governor Californians first saw 36 years ago.

Brown entered office following the 1974 Watergate election that decimated Republicans. He won that election by a relatively narrow margin and can probably thank President Gerald Ford’s pardon of former President Richard Nixon that September for his winning at all.

In the era of reformist liberalism that followed Watergate, Gov. Brown was daring as he filled his administration with activist Democrats. This time, however, he was elected in an otherwise Republican year nationwide where the mantra is budget cutting and deficit closing.

Brown has responded as one might expect. His budget cuts things the Democrats would never countenance under former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. And as in 1975, a nimble Brown seems quick to catch the political tide.

He has refurbished his reputation as one of the best practitioners of symbolic communications, conveying his ideas through actions that people can easily understand. In 1975, following the excesses of Watergate, the new governor did away with his official limousine and instead rode around in a blue Plymouth. The bachelor governor also rejected the governor’s mansion and slept on the floor of an apartment across from Capitol Park.

This time the symbolic acts include stripping state employees of their cell phones and extra state cars, and most amusingly his “ban on baubles” — such as Department of Transportation souvenir traffic cones and Department of Motor Vehicles crayons, something parents use to entertain their children while waiting at DMV offices. “We don’t need that stuff,” Brown said during a February press conference.

Of course there are no real savings in any of this, but it makes it sound like he is really doing things. People understand cell phones and crayons, if not the million-billion budget items.

But in his overall approach to the state budget, the new Jerry Brown has followed almost the exact path of the old Jerry Brown. When he came into office in 1975, one of the first things he did was immerse himself in the intricacies of the budget. In August 1975, the California Journal wrote of his budget: “This first Brown budget is rather dull in its contents. More interesting is the role the governor played in developing it, and in personally making each of the hundreds of decisions involved in writing the 194-page spending bill. No governor in recent California history has ever thrown himself into the fiscal morass as deeply as did Brown.”

The 2011 Brown has done the same thing. No one would ever accuse former Gov. Schwarzenegger of being a policy wonk. He saw his job as a salesman for the product his staff prepared. Brown sees himself as a decision maker down to smallest detail.

This is somewhat at variance with the image Brown likes to project as a far-sighted thinker. But, in fact, Brown both set the tone for this year’s budget and laid out the details. “The budget I propose,” Brown said in his January inauguration, “will assume that each of us are elected to do the people’s business and will rise above ideology and partisan interest and find what is required for the good of California. There is no other way forward. In this crisis we simply have to learn to work together as Californians.”

But the budget he presented was not one open to much negotiation. It was very much “implement my vision,” to quote the less successful Gov. Gray Davis. Brown did seem to succeed early on in seizing the high ground in the budget debate. This might have been expected given his long years dealing with legislatures and city councils.

There is also another side of Brown we are seeing in 2011 that was there in 1975 but largely missed by later observers: the skinflint. The efforts by the hapless Meg Whitman campaign in 2010 to paint Brown as some sort of tax-and-spend liberal were never going to stick because they weren’t true. The day after he signed the 1975 budget, Brown sent a memo to all his department heads: “I intend to take every step possible to avoid a general tax increase in the (next) fiscal year. Accordingly, new programs which cost money require corresponding reductions in other programs.”

The first Gov. Brown allowed a huge surplus to build, which helped trigger Proposition 13 in 1978. That’s not likely to happen again. But a look at the old Jerry is very helpful in appreciating how the new Jerry approaches his job.

Recommended For You

Hoops & Hurdles

The struggle to sell Jerry Brown's tax measure

If the people of California won’t vote to tax Big Tobacco or Big Oil, why does Gov. Jerry Brown think they’ll vote to tax themselves?

What They Don’t Tell You

The hidden agendas behind Gov. Brown's tax initiative

Gov. Jerry Brown’s tax measure would raise sales taxes by one-quarter of a percent for four years and increase taxes on incomes of $250,000 or higher by 1 to 3 percentage points for seven years.