For years, the debate over climate change centered almost exclusively on science: Is global warming occurring, and if so, are humans causing it? But with the economy still struggling, the argument has shifted to one of dollars and cents. As complex as the scientific debate has been, the fiscal reality of fighting climate change is even more politically charged — and confusing.

Nowhere is this more evident than in California, where an all-out battle is now under way to block state officials from implementing Assembly Bill 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, which requires the Golden State to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger later added an executive order requiring the state to achieve a 33 percent renewable energy portfolio by 2020. Senate Bill 375, a 2008 law sponsored by Sen. Darrell Steinberg, who represents Sacramento, has placed a heavy load on local municipalities as well by requiring them to account for greenhouse gas reductions in regional planning and development. Schwarzenegger has set an overall goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent by 2050.

National Conference of State Legislatures analyst Glen Andersen, who tracks greenhouse gas legislation, says these are the most ambitious goals in the nation. “A dozen states have adopted policies to combat climate change,” he says, “but none quite as aggressively as California.”

To its critics, the law is a boondoggle sure to lead to massive consumer price hikes and job losses without doing a thing to slow climate change. But to others, AB 32 is a godsend that will cement California as the global leader in clean technology, combating global warming, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs and spurring billions of dollars of new investment.

The controversy — like many others in the Golden State’s past — has made its way to the ballot box. This November, voters will weigh in on Proposition 23, a ballot measure that would halt AB 32’s implementation until the state unemployment rate falls from its current mark of 12 percent to an average of 5.5 percent or less for four consecutive quarters, a feat the state has rarely accomplished. Republican gubernatorial candidate Meg Whitman has also vowed, if elected, to enact a clause in the law allowing its implementation to be delayed for a year in the event of “extraordinary” economic circumstances.

Experts say the two sides in the battle over Proposition 23 could end up spending more than $150 million to make their case. If so, the ballot campaign would be among the most expensive in history.

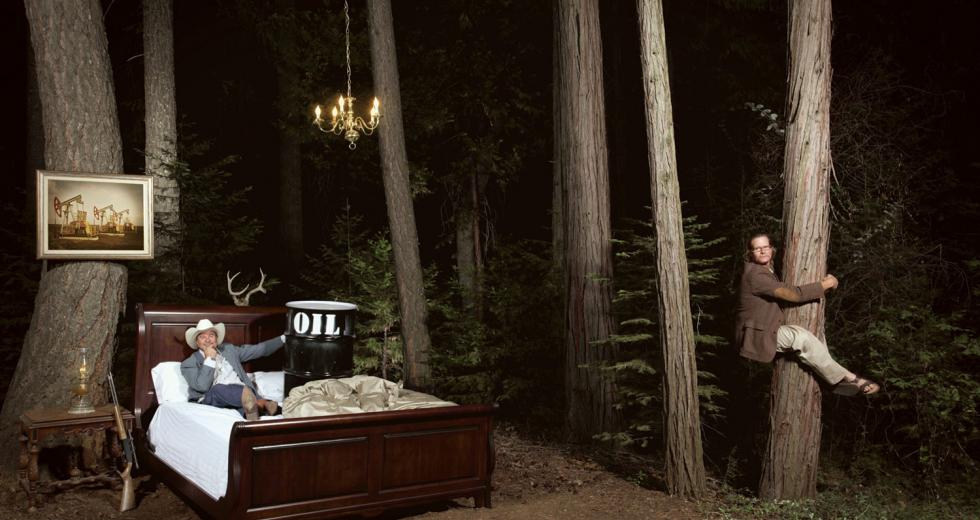

Much of the financial support for Proposition 23 has come from companies with a lot to lose under AB 32’s requirements, primarily a cadre of Texas oil companies like Valero Energy Corp. and Tesoro Corp. Anti-tax and pro-business groups — including the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association and the California Manufacturers and Technology Association, the state’s largest manufacturing lobby — have also helped fund the measure, though the state’s largest business advocacy organization, the California Chamber of Commerce, has not taken a formal position.

But AB 32 also has powerful supporters. Schwarzenegger, who has made greenhouse gas reduction a signature issue of his administration, is joined by a wide spectrum of advocacy groups, from the Sierra Club to the American Lung Association and AARP. A long list of clean-tech companies also oppose the ballot measure, as do Golden State icons such as Google, Levi Strauss & Co., Yahoo! and Whitman’s former company, eBay.

Bill Hauck, president of the California Business Roundtable, a nonpartisan business advocacy group based in Sacramento, says the split among the business titans has deep roots in the unknown.

“Part of the difficulty here is the anticipation of the potentially negative impact AB 32 will have on the California economy,” he says. “It depends to a great extent on how you implement the law.”

“Framing this as only about jobs is a completely dishonest argument. This is about our survival.”

Jacob Griscom, western regional manager, BetterWorld Telecom

That it does. The text of AB 32 is brief, only requiring the state to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 and providing no details on implementation. It has been left to the California Air Resources Board to fill in the blanks. With no clear guidelines for achieving such an enormous goal, the board has devised a “scoping plan” that includes a mix of direct regulations, voluntary compliance mechanisms and incentives for both industry and consumers. In all, the plan has more than 70 measures, and the average consumer isn’t likely to notice many of them.

But the plan also has several major components, most of which go into effect by 2012. These include mandates for car manufacturers to cut new vehicles’ greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2016 and for petroleum companies to reduce the carbon content in automotive fuels 10 percent by 2020. Energy efficiency is also key with financial incentives for consumers to upgrade their homes’ heat and air systems. The state is asking many industries to upgrade their equipment, particularly those that emit “high global warming potential gases” like refrigerants, which the Air Resources Board says “trap heat in the atmosphere at levels many times that of carbon dioxide.”

But no element of the scoping plan is larger or more controversial than the proposed carbon cap-and-trade program, the one significant part of the whole greenhouse gas reduction process that relies on free-market ideals. It works like this: The state sets a cap on the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions the largest industries can produce in a given year. Most will come from one of three sectors: transportation, manufacturing or electricity production. These entities, more than 600 across the state, are then granted allowances to produce a certain amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Those companies can then either use their full allotment or, if they don’t need that total, sell or trade their permits on the open market to other companies that will exceed their own cap limit. Over time, the number of allowances will drop, forcing companies to either emit less greenhouse gas each year or pay a significant fee. In theory, this will force industries to become more efficient and pollute less. The Air Resources Board estimates the program will effect 85 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas sources and shave 34 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from the system by 2020.

There has been some debate over that last figure, but it pales in comparison to the dissension over how the law will impact the state’s economy. Both sides have produced numerous studies supporting their stance while vehemently debunking those put forward by the other side. Most pretty much say what their supporters want them to say, but some concerns cannot be uniformly cast off, most notably: What happens if California’s cap-and-trade program is not joined by other states?

As a member of the Western Climate Initiative, a coalition of seven Western states and four Canadian provinces, California is counting on those partners coming aboard around the same time its system is set to go in 2012. But with at least one of those states, Arizona, moving to halt its greenhouse gas reduction efforts, it probably won’t happen. If it does not, the Legislative Analyst’s Office says California consumers could indeed face higher across-the-board prices for most goods and services as well as job losses brought on by “economic leakage” as companies leave for states where the cost of doing business is cheaper.

That possibility rankles California Assemblyman Roger Niello.

“I think it is absurd for a single state to pursue a policy that seeks to affect something on a far and wide basis all by itself,” says Niello, a Republican. “For one state to adopt a policy to eliminate carbon dioxide emissions, and only one state, is complete folly.”

Supporters of AB 32 counter that California would not be the only state with a carbon cap-and-trade program, even if the other coalition states bail out. Ten Northeastern states have managed a cap-and-trade program since the early 1990s, first to deal with acid rain and then, in 2003, moving on to carbon reduction under the flag of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. The European Union also has a carbon cap-and-trade program.

“I think it is absurd for a single state to pursue a policy that seeks to affect something on a far and wide basis all by itself.”

Roger Niello, California assemblyman

But Dorothy Rothrock, vice president of government relations for the California Manufacturers & Technology Association, is not swayed by that argument.

“The states in the RGGI are not really our competition here in California,” she says. “Even if AB 32 is implemented under the best-case scenario, prices are going to rise over the long haul.”

According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, most of the negative impacts of AB 32 would be “near term” and “likely be modest relative to the overall size of California’s economy.”

Supporters are also quick to mention that California’s greenhouse gas reduction efforts are about more than economics.

“Framing this as only about jobs is a completely dishonest argument,” says Jacob Griscom, western regional manager for BetterWorld Telecom, a Virginia-based company that focuses on businesses practicing sustainability. “This is about our survival.”

Warren Smith, CEO of Sacramento-based Clean World Partners, which builds solid waste conversion systems that divert waste from landfills, is even more blunt.

“Saying this will cost jobs is just bull,” he says, noting that AB 32 has already given California a significant head start in the green economy, spurring 60 percent of all green-tech venture capital in the country — more than $9 billion so far — to come to the state. Smith says the private sector is actually moving more quickly than government in adapting to cleaner and more energy-efficient processes, citing Walmart and S.C. Johnson & Son Co. as just a few of the Fortune 500 companies already making great efforts to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. But he also says the private sector can’t act alone.

“Change is always hard, but we need government to lead on this,” he says.

For all the rhetoric, the outcome of the state’s greenhouse gas reduction program is far from certain even if voters approve Proposition 23. While many say the measure’s passage will stop that effort in its tracks, Jon Costantino, a former air resources manager who was intimately involved with the development of the scoping plan, isn’t so sure.

“The ballot measure would kill anything under AB 32, but a lot of things are not under that umbrella,” says Costantino, now a senior adviser in the Sacramento office of law firm Manatt, Phelps and Phillips LLP. “We would lose the cap and trade and some others, but things like SB 375 would still go on. The clean car standards are not part of AB 32, so they go on.”

Most observers say Washington is also keeping a close eye on California. Climate change legislation very similar to AB 32 has floundered in Congress with no rational person willing to bet that such a piece of major legislation will ever get through. But Steve Maviglio, a spokesperson for the group opposing the ballot measure, says it could change if California voters reject Proposition 23.

“If it goes down in flames, it will send Washington a pretty strong message that voters want this done,” Maviglio says. Left unsaid is the reality that the opposite is also true.

Recommended For You

Air Conditioning

Emissions standards target key industries

If there is one thing a business owner hates, it is uncertainty. Planning for the future — or even managing the present — cannot effectively happen unless the person signing the checks knows the rules of the game. But when it comes to California’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, uncertainty is about the only thing employers can count on right now.

Growing up Urban

The political climate of land-use planning

For decades, devising a clear solution for California’s suburban sprawl and ensuing car culture has been the Holy Grail for smart-growth advocates. One trip on any of the Golden State’s perpetually clogged roadways during peak hours shows how ineffective most of those efforts have been.