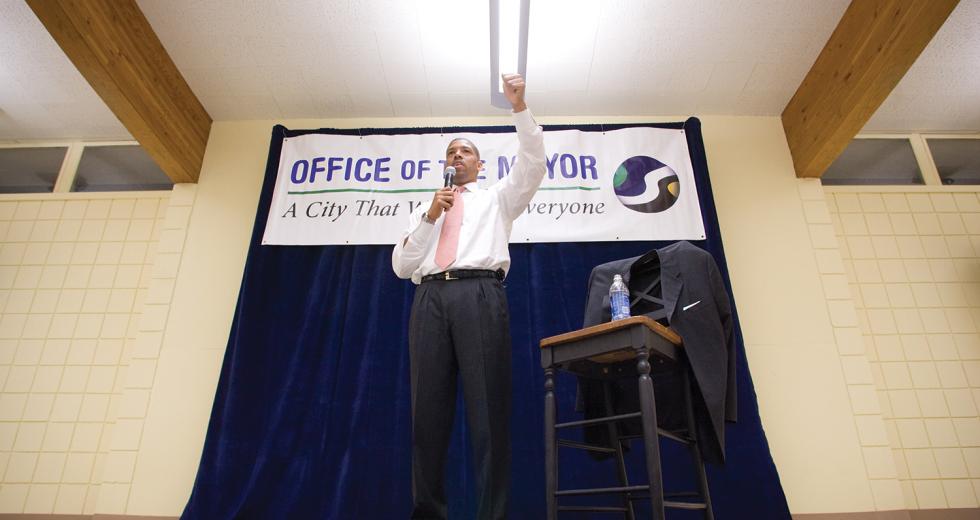

From the moment Kevin Johnson began his 2008 campaign to unseat Sacramento Mayor Heather Fargo, he promised that, if elected, he would shake things up at City Hall. Now, slightly more than a year into his tenure, nobody can deny he has kept that promise. Whether it’s good or bad for the city, however, depends on whom you ask.

“The energy level at City Hall is exponentially greater. He has re-energized many older employees,” says Sacramento State communications professor Barbara O’Connor, a nationally recognized political observer.

These days, the suggested spike in the energy level at 915 I St. is Johnson’s go-to topic as well.

“City Hall has a new energy,” he says. “It’s not just business as usual.”

Such talk makes it hard not to think back to Johnson’s basketball days, first at UC Berkeley and then with the NBA’s Phoenix Suns. As mayor, Johnson still moves in much of the same high-octane way that the blindingly fast “KJ” would on the court, often leaving frustrated opponents in his wake. No one then — not defenders, teammates or even his coaches — could control him.

The late Lowell “Cotton” Fitzsimmons, Johnson’s coach during the Suns’ halcyon days, once noted that his star point guard often disregarded set plays in favor of action on the fly. The wry Fitzsimmons added that he eventually stopped butting heads with Johnson over it because far more often than not, the plays worked.

“Kevin doesn’t do anything unless he knows why he’s doing it,” Fitzsimmons said at the time. “As a coach, it was easy for me to just hand him the ball and let him do what he does best.”

The Kevin Johnson of 2010 appears to be no less headstrong. Never physically imposing, he is nonetheless still athletic and trim, with the same dazzling smile that has helped him keep his national presence long after his playing days ended. Most importantly, he can still commandeer an issue in a way that leaves other spotlight seekers just as discouraged as the poor overmatched fellows that once tried to deter him on the court.

But that willingness to push full-steam ahead at all times has also produced frustration among his allies and enemies. Never has this been more evident than in reaction to Johnson’s “strong-mayor initiative,” his controversial effort to obtain significantly more control over how the city is run. Under the proposal, which voters will decide in June, the mayor would gain the power to hire and fire hundreds of city employees and officials, including the city manager, treasurer and attorney. He would also propose a budget and have veto power over City Council decisions. The council would retain override power subject to a two-thirds vote.

That’s a far cry from the current arrangement in which the mayor is only one of nine council members, with nary an additional duty beyond cutting ribbons and overseeing meetings. The strong-mayor initiative has sparked significant pushback from several people who were once among Johnson’s strongest supporters, including at least half of the City Council and Sacramento Central Labor Council Secretary Bill Camp, who has filed suit to have the measure tossed off the June 8 ballot.

Camp was an early backer of Johnson’s mayoral candidacy, something he says did not endear him to the Sacramento labor movement. “I took an enormous amount of crap from my friends and colleagues over that,” he says, noting that many in labor supported Heather Fargo. Camp says he still supports Johnson and is not suing him directly.

“I came in with my guns blazing. People weren’t ready for that.”

Kevin Johnson, mayor, city of Sacramento

“I’m suing the city of Sacramento and the city attorney,” he says. “Our disagreement is over the process.”

That process, Camp argues, is a major revision in the city charter, so it’s not legally able to change through a ballot measure. The issue, he says, is giving the mayor so much control over city workers.

“This is a civil service town,” he says. “It is simply a mistake to give the mayor that much power over the civil service system.”

At a press conference held shortly after the suit was announced, Johnson expressed his disappointment, calling the proposal the will of the people.

“People came up to me all the time during my campaign to ask why the city manager, who isn’t even elected by the people, has so much more power than the mayor,” he said at the conference. “People don’t understand that.”

The proof, he claims, is that more than 50,000 people signed petitions to get the proposal on the ballot. (The city registrar validated just over 35,000 of those signatures.)

Camp scoffs at that notion. “Don’t tell me that 35,000 people know what’s in that petition,” he says. “Most of the people didn’t even read it. They were just talked into signing it by a bunch of paid petition gatherers.”

Camp says he still admires what Johnson has done to help elevate the city’s national profile — calling him “a great ambassador for Sacramento” — but says even if the court doesn’t yank the strong-mayor initiative off the ballot, “there’s not a snowball’s chance in hell it will pass.”

To date, polls show he may be right: Only about 30 percent of eligible voters favor the initiative. If that were Johnson’s only interest, it might really be cause for concern. But Johnson is anything but a one-trick pony. He has thrown himself with gusto into pursing what O’Connor calls “a scattershot of ideas,” from putting more cops on the streets to funding arts to dealing with the city’s growing homeless population. As if that was not enough, he has also taken on some of the city’s longest-standing development issues, including a K Street makeover and finding a way to replace the rapidly deteriorating Arco Arena.

He has unquestionably made some headway in several of these areas, although at times in a manner that can rub people the wrong way. Case in point would be the task force he chairs proposing to put more than 100 homeless women and their children into temporary housing at Mather Community Campus without first adequately discussing it with city officials in Rancho Cordova.

But for each clunky mistake, Johnson has had a corresponding effort that seems only he could pull off. Using his star power, Johnson has forged relationships with the likes of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, which has made Sacramento the pilot city in a new $500,000 program designed to help struggling schools maintain arts education during bad economies. The program, known as Any Given Child, will link the city’s professional arts organizations with schools to develop a course of action for ensuring the arts stay a part of the curriculum.

Johnson has also made inroads with a bevy of national education leaders, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and New York City Schools Chancellor Joel Klein. His strongest connection yet may be the one he has forged with the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, which has signed on to help underwrite an ambitious education initiative Johnson has dubbed “Standing Up for Sacramento Schools.” Under the agreement, Broad will give the program $250,000 in seed money, with promises of another $250,000 down the road if Johnson can match the $500,000 with funds raised locally.

“We have to stop being afraid of the idea of the perfect failure. We must try big ideas even if they fail, otherwise nothing gets done.”

Rob Kerth, executive director, Midtown Business Administration

“He believes very strongly in my passion and track record,” Johnson says. “He is essentially helping us leverage $1 million to help us create an environment in Sacramento where we can focus on the education needs we feel are most important.”

Creating that environment, Johnson says, would entail enacting several items that came out of an education summit he hosted last March. Those ideas include issuing Sacramento schools an annual report card, recruiting the best teachers, authorizing more charter schools and greater leveraging of external funding sources like federal stimulus money.

An agenda this big would be a challenge to fulfill in the best of times. These, however, are not such times, either fiscally or politically. The strong-mayor proposal has engendered an in-house feud at City Hall, where opponents claim Johnson is trying to establish a Chicago-style political machine.

In the business community the rift has also sparked fear that a mayoral takeover of duties currently belonging to City Manager Ray Kerridge could force the popular Kerridge to look for new environs. Business leaders credit Kerridge with easing development restrictions that, according to a letter more than 60 business leaders sent to Johnson and the City Council in December, have led to “great strides in our economic and development departments.” The group, which includes restaurateur Randy Paragary, Armour Steel CEO Steve Ayers and developer Mike Heller, hasn’t taken an official stance on the strong-mayor initiative, but is considering forming its own political action committee to formally oppose those politicians it considers to be “anti-Sacramento.”

Whether Johnson falls into that group remains to be seen. The mayor had become a lightning rod for controversy long before introducing the strong-mayor issue, with questions surrounding everything from his financial management of St. Hope Academy — his signature Oak Park charter school — to his pending marriage to Washington D.C. schools chancellor Michelle Rhee. But former City Council member Rob Kerth, who is now the executive director of the Midtown Business Association, believes Johnson “had a great first year” in spite of all the head knocking.

“He got some lessons,” Kerth says. “I call it his Lilliputian year: All the little people have him staked down pretty good. I don’t think he expected that.”

Part of that, Kerth says, is that Johnson has unsettled the status quo. “There is always a huge fear of the unknown,” Kerth says, adding that the strong-mayor initiative “wasn’t proposed or drafted well.”

Shawn Eldredge, a former mayoral candidate who is now running for the City Council, counts himself among those who once supported the initiative but who have since turned against it. Eldredge says the proposal will only worsen the council’s current discord.

“The strong-mayor initiative will make the City Council completely dysfunctional,” he says. “We’re going to see nothing but petty power plays all the way into the next election cycle.”

Eldredge also accuses Johnson of creating chaos on the council by demanding members go along blindly with his agenda.

“Johnson doesn’t reach out in a two-way conversation,” Eldredge says. “He shows up and says, ‘This is my way. Join up or else.’”

Johnson disputes talk of his rift with the council, saying, “A lot of this has been blown out of proportion. There are really not a lot of issues that separate us.” He says, however, that his hard-charging style may have been a bit much for some to handle.

“I came in with my guns blazing,” he says. “People weren’t ready for that.”

With that in mind, he says, “I have to do a better job of gaining a collegial atmosphere when the City Council disagrees.”

“[Kevin] is a big-picture person who doesn’t care about the nuts and bolts of government.”

Shawn Eldredge, former Sacramento mayoral candidate

Johnson also says he doesn’t plan to remove Kerridge if the strong-mayor proposal passes. Kerth says Johnson is being straight on that one because such a move wouldn’t benefit the mayor.

“There is no reason [them working together] wouldn’t work well and lots of reasons that it would,” he says.

While some critics contend Kerridge has been too lenient with developers, Kerth lauds him for helping to make the city more willing to take chances with potentially large benefits.

“Ray has instilled in city government an acceptable level of mistakes. That’s a huge step for Sacramento,” he says.

Eldredge also shrugs off fears that Johnson would want Kerridge to leave.

“Kevin is not a wonk,” Eldredge says. “He is a big-picture person who doesn’t care about the nuts and bolts of government. That’s not necessarily a bad place for him to be.”

Kerth also says there is a high likelihood the current rifts on the council will remain no matter what happens with the strong-mayor initiative. For now, however, the vested parties appear to have toned down the rhetoric. Some of Johnson’s most vocal critics on the council, Kevin McCarty and Rob Fong, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Ray Kerridge politely declined, while several of the business leaders who signed the letter to Johnson and the council also declined to speak or did not answer requests for comment.

“Only time will tell if Johnson’s agenda will work,” says Sacramento State’s O’Connor, who blames much of the mayor’s troubles on a lack of experience. “Kevin hasn’t developed a political filter. That is bound to get detractors.”

Whether he develops that filter or not, Kerth says Johnson’s heart is in the right place. He also lauds him for risking all of his political capital to try and accomplish his goals.

“We have to stop being afraid of the idea of the perfect failure,” Kerth says. “We must try big ideas even if they fail, otherwise nothing gets done.

Recommended For You

Mayoral Musings

'Strong Mayor' will make city more nimble, NBA matchmaking and soccer in Sac

It’s been quite a year for Sacramento Mayor Kevin Johnson, topped in most people’s minds by his stunning, come-from-behind effort to block the Maloof family from selling and relocating the Sacramento Kings. We sat down with him recently to discuss basketball and several other topics important to the Capital Region.

What Would Joe Serna Say?

Sacramento might be ready for a strong mayor

We’re at it again. For the fourth time in five years, the political conversation in Sacramento is focused on whether to change the city’s governing framework from the current council/city-manager structure to a so-called strong mayor system that boosts the mayor’s authority.