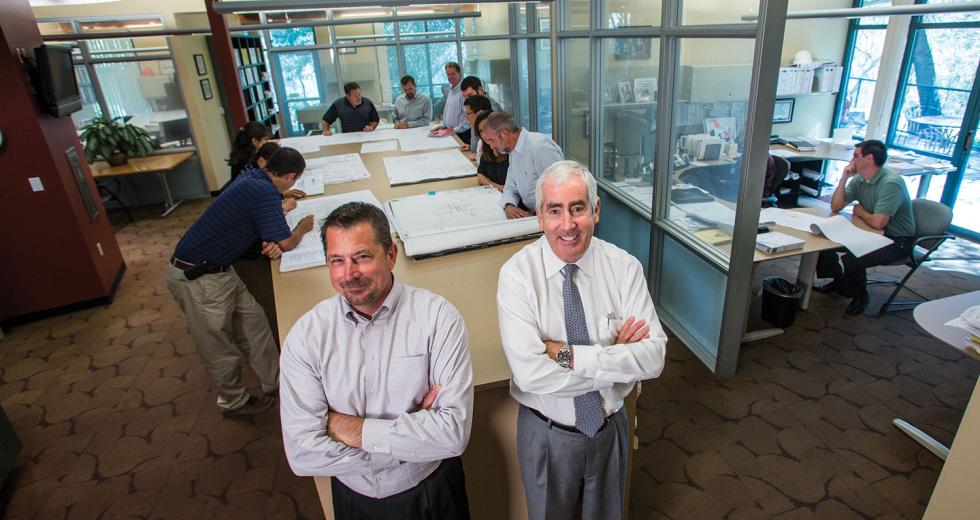

It was sometime in 2004 when Larry Booth and his brother Martin swallowed the truth that they wouldn’t live forever.

Larry Booth was 56, Martin 60, and they represented the third generation of family ownership of Frank M. Booth Inc. They needed a succession strategy, and after exploring the options determined an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), which would turn employees into company owners, was the best avenue for the business and its team. “In our business, there are a lot of successful companies that are ESOPs,” Larry Booth says. “That track record, plus the commitment the federal government has shown toward supporting ESOPs, made going that route the best choice and one that will benefit us and the team for another hundred years.”

The Booths’ ESOP took effect in January 2006, and since then it has lived up to the hype, offering attractive tax benefits; a more productive, enthusiastic and loyal workforce; and, ultimately, a better employee benefit than a 401(k) or other retirement program.

In its most simplistic definition, an ESOP is both an employee retirement plan and a corporate tax vehicle that reduces or eliminates income tax while providing an exit strategy for company owners. ESOPs are similar to profit sharing plans but are designed to invest primarily — if not completely — in the employer’s stock and are not required to diversify investments.

“Everyone knows the rule of not putting all their eggs in one basket, but ESOPs are specifically written to be the opposite,” says Kevin Long, shareholder in the law firm of Chang Ruthenberg & Long. “All the advantages of ESOPs come from that difference.”

Chief among the tangible benefits for the company are the tax advantages. Similar to other benefit plans, the contributions a company makes to the ESOP are tax deductible. Unlike other programs, however, an ESOP can be established with a bank loan wherein the principal and the interest paid are both tax deductible.

“Even better, the company can even pay dividends on the ESOP company stock and then take a deduction,” Long says. “It’s the only deductible dividend in the internal revenue code.”

Perhaps the greatest tax incentive, however, is the impact an

ESOP can have in reducing or even eliminating the corporation’s

income tax. In short, an ESOP is a tax-exempt trust. Certain

rules apply, but whatever percentage of the company the ESOP owns

is also the percentage of the company income that goes untaxed.

Companies that are 100 percent ESOP-owned could pay no income tax

at all. Moreover, in some circumstances, owners who sell their

companies to an ESOP can defer capital gains tax by reinvesting

within a certain time, just like a home sale.

“Everyone knows the rule of not putting all their eggs in one basket, but ESOPs are specifically written to be the opposite. All the advantages of ESOPs come from that difference.”

Kevin Long, shareholder, Chang Ruthenberg & Long

The intricacies of these benefits are complex, so establishing a plan is best left to an attorney who specializes in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

“It takes time and a really good ERISA attorney,” says Dennis Dalton, CFO of Western Contract, which established its ESOP in 1991. “ESOPs are closely regulated by the IRS and the Department of Labor, and you don’t want to mess around with either of them. Get a good attorney, and make sure it’s done right.”

Another less tangible but very real benefit is that ESOPs usually change the relationship employees have with the company for the better. ESOPs can be a huge boost for morale, retention, recruitment and productivity because, while employees’ jobs don’t change, their reasons for working do.

“Having an ESOP in place changed the culture of our company,” says Bev Cooper, benefits manager with Building Materials Distributors Inc., which launched its ESOP in 1991. “People have more of a teamwork attitude because the better we do our jobs, the more we benefit.”

That same culture is shared by the employee-owners at Sleep Train Mattress Centers, which started its ESOP in 2010.

“The ESOP empowers employees to treat the business like it’s theirs, and it’s an acknowledgement that the company’s success is due to everyone’s contribution,” says Tracy Jackson, Sleep Train’s vice president of human resources. “Employees make better decisions because they hold themselves and their co-workers accountable, and they see the direct result of their work translated into dollars for their retirement.”

Sleep Train’s share value increased 156 percent last year. It’s doubtful any public stock matched that, and none of the major indexes came anywhere close. Claims that ESOPs are good for the company are more than just anecdotal — nearly a dozen research studies have been done in the past two decades, and the overwhelming weight of evidence concludes ESOPs can have positive impacts on the bottom line.

In 2000, Rutgers University published the largest study on the subject after surveying more than 300 ESOP companies and comparing them with similar non-ESOP employers. They found ESOP companies enjoyed an increase in employee productivity of 4.4 percent, showed increased sales overall, increased employment and increased sales per employee. A similar study of 30 ESOP companies by the University of Michigan concluded ESOP companies were 1.5 times as profitable as their non-ESOP counterparts.

“ESOPs are closely regulated by the IRS and the Department of Labor, and you don’t want to mess around with either of them. Get a good attorney and make sure it’s done right.”

Dennis Dalton, CFO, Western Contract

Compelling as the research is, however, no one should mistake an ESOP for a magic spell that will improve morale, productivity and revenues overnight. News about an ESOP can backfire, and ESOP companies can and have failed.

The difference lies in making sure the company is right for an

ESOP. First, there are minimum requirements for any company to

establish an ESOP; it must have been in business and shown a

profit for at least the previous three years, for example.

ESOPs are also likely to be difficult for companies that have fewer than 20 employees, have high employee turnover, rely heavily on contract workers, have high external risk factors (such as tech companies at risk of obsolescence) or cannot function without an owner.

Furthermore, a good management team is essential, and company culture is critical. A top-down business will struggle more than a business in which employees already have some autonomy.

Costs to get started and annual fees for stock valuations — which require third-party expertise and must be accurate — are significant: $35,000 to $50,000 to start, plus annual fees for stock appraisals and record keeping as high as $10,000. Tax benefits may backfill those costs over time, but from a debt and cash flow standpoint, it’s a spending decision that must be penciled out carefully.

Finally, clear and ongoing communication with employees is essential. They need to understand what “ownership” through an ESOP means and does not mean. It does not mean they have a voice in management decisions. It’s just like owning stock in any other pubic company — there are votes on some matters, but setting the direction of the company is left to the executive leadership. That message is just as important for management as it is for the shop floor.

Likewise, how employees get “paid” by the ESOP can be another gray area. They need to know they aren’t getting cash in their pocket every year the stock goes up. An ESOP is not a salary — it’s a retirement plan that keeps shares of the company in trust and can only be cashed out when an employee is fully vested and leaving the company.

“It’s important to make sure employees really understand what’s in it for them,” says Tim Baer, manager of automated systems and member of the ESOP committee at Frank M. Booth Inc. “Make the investment in showing employees how they benefit from the program because the greater the number of employees that ‘get it,’ the greater the bottom line results will be for the company and its new shareholders.”

ESOP 101

ESOPs provide the only deductible dividend in the internal revenue code.

Scenario: You own a business worth $100,000. You’d like to retire and sell the business to your employees through an employee stock ownership plan, or ESOP. When the business was created, 100 shares were established, so each share is now worth $1,000.

Step 1: The company gets a loan from the bank (or from you) for the full value of the company, so, in this case, $100,000, assuming a complete sale rather than sales that phase in over a few years. It’s a 10-year loan. Ten percent ($10,000) plus interest is paid back every year.

Step 2: The company re-loans the $100,000 to the ESOP.

Step 3: The ESOP pays you the $100,000 to buy the company. In exchange you put all 100 shares into the ESOP, which keeps them in trust for the employees. At this point, the company is 100 percent ESOP-owned and pays no income tax.

Step 4: At the end of year one, the company makes a contribution of $10,000 to the ESOP. Because this is a contribution to a retirement program, it is tax deductible. The ESOP then makes a loan payment in the same amount to pay down the loan. That loan payment, both the principal and the interest, are also tax deductible.

Step 5: After the loan payment, the ESOP has $100,000 in assets and only $90,000 in debt, meaning $10,000 worth of shares are now unfettered from the bank and can be distributed to employees. The employees aren’t handed actual shares, however, they are held in trust by the ESOP until the employee is fully vested and leaves the company, at which point those shares are sold back to the ESOP.

Step 6: The process continues until the loan is paid off, at which point 100 percent of the available shares have been distributed to the employees. In some circumstances, as the stock value goes up, the company could also pay employees a dividend on the stock value, either in cash or as an ESOP contribution, in which case the dividend payment would be tax deductible.

Step 7: Once the loan is repaid, the ESOP could

simply “stop” — no more contributions would be made, and

employees would simply enjoy (hopefully) growth in the value of

their shares. As another option, the company could decide to

issue more shares and continue the program, or the company could

just make cash contributions to the ESOP, giving it a new asset

to hold in trust for employees along with their company

shares.

Recommended For You

Investment Property

The return of 100-percent financing

Remember the wild days of the real estate boom when you could buy a house with nothing down? You still can. Well, maybe you can’t, but a very select group of wealthy buyers can.