An icy breeze hits the hills of El Dorado County, rushing through a den of ponderosa pines and incense cedars that face a sweep of lifting mountains. This hideaway of trees stands at the 3,000-foot elevation mark. Its long branches shade a family winery that’s been growing riesling grapes here since 1973. The place is named Madroña Vineyards for the crimson hue its scattered madrone tree trunks bring to the outdoor color scheme. It was the second drinking destination to open on El Dorado’s storied wine trail, and it was one of the first in California to experiment with high-elevation vintages.

On this frigid morning at Madroña, the clouds are stark, and the gale is cutting — a kind of metaphor for the news headlines that have recently brought doomcasting to the state’s wine industry. After three decades of growth, the industry has seen three years of negative sales. The problems are varied. Grape farmers are being severely undercut by cheaper bulk wine from abroad. Sudden, unpredictable tariff shock is knocking exports and profit margins off kilter. And there’s been studies of late suggesting that Gen Z, those born between 1997 to 2012, is abandoning the wine life and maybe even alcohol altogether.

It’s been a cold metaphoric winter for the area’s wineries.

But beyond Madroña’s front door, owner Paul Bush is perfectly relaxed as he handles a bottle of grenache inside the warm, cabin-like ambiance of his alpine tasting room. Bush’s family has seen these headlines come and go since first planting their vines during the Nixon administration.

“We’ve been doing this for a long time — 50-something years,” Bush reflects. “We’ve seen the rollercoaster ride of the industry. You can go all the way back to the 1980s when everybody was planting zinfandel, and all of the sudden zin was no longer the variety people wanted to drink. But even there, you had the invention of white zinfandel, which then blew up and saved a lot of vineyards. Many times in the past, people have prewritten the future of wine, and they’ve done it prematurely.”

Bush adds, “I suspect that we are looking at a three or four-year lull, but the trend line will stay slowly upwards, with ebbs and flows.”

Is Gen Z saying ‘au revoir’ to vin?

Future growth requires future consumers, so when Gallup released a report two years ago indicating that young adults are drinking less alcohol than the generations before them — and significantly fewer Gen Zers are drinking on a regular basis — it sent a wave of concern through the wine world. Specifically, Gallup detailed that it had found “a marked increase from earlier readings in Americans’ belief that even moderate drinking is bad for one’s health.”

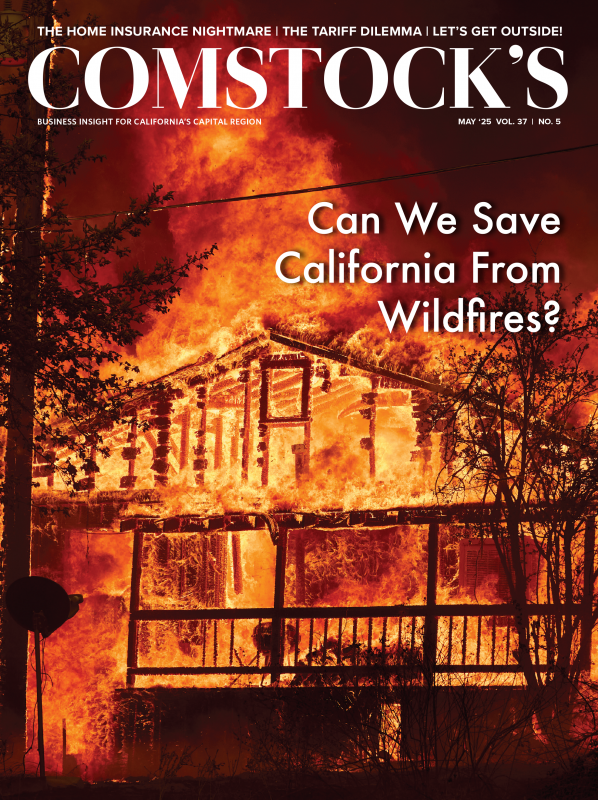

Paul Bush, owner of Madroña Vineyards, in his winery tasting

room. He’s been in the winemaking business 50 years and says it’s

always been a rollercoaster ride.

In the last four years, Movendi has also successfully lobbied some officials within the World Health Organization and the U.S. National Institutes of Health to parrot its “no safe consumption” messaging, despite the fact that the aggregate findings from public health’s gold standard study on the matter — the Global Burden of Disease study — has repeatedly determined that there is a safe level of alcohol consumption, which is different for men and women.

But even for Gen Zers who are imbibing drinks, some are concerned this cohort is trending towards different preferences. In 2024, a Gallup survey found that among adults age 18 to 34, 42 percent favored beer, 36 percent favored distilled spirits and only 20 percent favored wine.

Those numbers aren’t rattling Bush, though. He just got back from the WiVi Central Coast wine symposium where more uplifting data was presented. Bush says that at that event put on by Wine Business Monthly there were new findings to suggest young adults are a big market of opportunity with the right storytelling. And that tracks with Bush’s personal observations. He believes the industry has done a disservice to younger drinkers by presenting wine tasting as an overly complex endeavor, rather than emphasizing what is different and exciting about it.

“They had some pretty impressive numbers at WiVi that don’t count out the Gen Z and millennials as wine drinkers,” Bush reports. “It’s more about understanding what they’re interested in. … There are chances to educate that group, especially if you’re in a region like ours that has better price points on quality, but also a true sense of place behind it — an area where the winemaking captures its essence and reflects the passion of its winemakers.”

Holly’s Hill Vineyards & Brewery in El Dorado County isn’t panicking, It’s pivoting. Winemaker Josh Bendick added a brewery at the winery along with daily food offerings. “Crafting small-batch beers alongside our Rhone-style wines lets us tap into a growing audience while staying true to our artisanal ethos. The brewery isn’t just a side project; it’s a celebration of the same creativity and terroir that define our wines,” Bendick said in a blog post.

One county south in Amador, vino trailblazer Bill Easton has a similar view. Easton has been a driving force in California’s Rhône-style wine movement since the 1980s, showing the way with his award-winning bottles from Terre Rouge and Easton Wines. Easton doesn’t discount that some of the Shenandoah Valley’s tasting rooms are struggling. He knows they might be seeing fewer young faces, too. One solution Easton advocates for is better media coverage of wine’s relationship to California culture, viewed specifically through the lens of different generations.

“We need monthly columns or better stories about what it brings to each generation’s lifestyle,” Easton suggests. “That would share the positive elements wine brings to the lived experience of each.”

Tariff turmoil

While Easton loves discussing how wine brightens our ways of living, lately he’s been forced to speak up about the fallout from constant tariff announcements. Canada is the top export market in the world for wine from the Golden State, spending over a billion dollars on it annually. In late winter, the White House announced an impending 20 percent tax on wines from abroad, as well as a 25 percent tariff on most Canadian foods and goods.

Winemakers like Easton had orders from Canada canceled indefinitely as American alcohol products were stripped from that nation’s store shelves. For Easton, who’s been doing business in the Land of the Maple Leaf for three decades, the effect was immediate. He’d been to Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City numerous times to host educational tastings, but the Trump tariffs may have nullified all of that work.

“My Canadian business is shut down as of now,” Easton says. “Already, it’s a loss of several hundred thousand dollars. Ordinarily, I probably do a million dollars of business in Canada every year. I’ve spent 35 years developing that market, and what worries me is, even if all these tariffs get cancelled, it’s going to poison the well by hurting longtime relationships.”

Erlinda Alexandra Doherty, a veteran policy consultant in the wine industry, worries many vintners could lose market access. Doherty is based in Washington, D.C., and works with wineries up and down the West Coast. She says every corner of the American wine industry is reeling from tariffs, with a general consensus that financially punishing European producers will not, in turn, make California vintages more affordable at home.

“It’s not like if they raise the price of toothpaste, I’ll just get another toothpaste,” Doherty emphasizes. “Wine is too specific of a product. A rioja from Spain is not the same as a California chardonnay. Wine enthusiasts aren’t necessarily going to switch out one for the other. They’re not necessarily going to drop a sangiovese from Italy for a sangiovese from Mendocino County.”

As the trade war escalates, small California winemakers will also face a rise in the overall cost of doing business. Most of their barrels come from France. The glass they use comes from China and Mexico. Their corks come from trees in Sardinia and Portugal.

“The juice from the vine might be American, but everything else ancillary to that project comes from other places,” Doherty points out. “American wine is still largely an international product.”

Getting raked on grapes and a turn towards home

Stuart Spencer’s family has been embedded in Northern California winemaking for half a century. So, when the region’s grape-growing market is off, he has to speak uncomfortable truths.

Spencer’s parents began planting grapes in 1970 for the company that would eventually become St. Amant Winery, now an award-winning cornerstone in San Joaquin’s wine-producing scene. Spencer has also been the executive director of the Lodi Winegrape Commission for years. He knows the health of the Capital Region’s grape market directly impacts the health of the winery community. That’s because a lot of vino-making operations also get revenue from growing and selling grapes to other buyers. This business model was good for 30 years of steady growth. But lately, less so.

“Growth hides problems, and there were structural problems in the industry that now are much more apparent, which is manifesting itself in the form of a lot of grapes going unharvested for the last few years,” Spencer says.

He adds there’s been a reluctance from his fellow growers to speak out because many still do business with California’s mega-wine producers, whose import decisions are now causing the pain.

“At the core end of this problem is the largest wineries and the largest grape buyers have been off-shoring grapes and bringing in cheap bulk wine from many parts of the world,” Spencer contends. “And the bulk is able to come here for cheaper than what we can produce it for.”

Worse yet, the federal government is subsidizing this trend through a loophole in federal trade law called the Duty Drawback program. Spencer says it incentivizes imports by refunding the alcohol taxes on wine bought from abroad.

The winegrape commission that Spencer leads has been monitoring American outsourcing from far-off vineyards, while two other organizations — the Allied Grape Growers and the California Association of Winegrape Growers — have been attempting to calculate what the trend means to vineyards across the state. Their estimates for the number of California grapes left unharvested last year range from 300,000 to 500,000 tons.

Spencer has seen that bleak reality in Lodi’s fields.

“When the rug gets pulled out from under you like we’ve seen the last couple of years, there’s no outlets to go to,” he says. “The wineries that have excess wine, there’s no bulk market to move inventory. There’s no market for their excess grapes.”

At the moment, grape growing associations on the West Coast are hoping they’ll eventually get the Trump administration to change or eliminate the Duty Drawback program. It’s allowing companies that are US-based to go elsewhere for production, which seems to be the antithesis of the president’s stated agenda.

In the meantime, Spencer thinks one practical solution to help Lodi and Sierra Foothill wineries is for area customers and businesses to put a greater focus on them: He’s noticed there’s still plenty of room on local store shelves and restaurant wine lists for brands that are fed by Northern California sunshine.

“We need to redouble our efforts on supporting local,” Spencer stresses. “We need people walking the walk and not just saying they support local.”

–

Get all the stories in our annual salute to women in leadership delivered to your inbox: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

A (Feminine) Touch of Tuscany in Amador County

Founder of Teneral Cellars aims to empower women with every bottle

Teneral Cellars winery in Plymouth is an award-winning, women-owned and self-proclaimed disrupter in the industry. It’s also an oasis in the Shenandoah Valley that’s less than an hour’s drive from Sacramento, though reminiscent of a picturesque wine region in Italy.

The Capital Region’s Charcuterie Entrepreneurs Are Turning Grazing into a Gourmet Experience

Charcuterie boards gained national attention from the business crowd in 2022, when Aaron Menitoff and Rachel Solomon Fascitelli, co-founders and co-CEOs of the online cheese and charcuterie gifting business Boarderie, appeared on “Shark Tank,” eventually walking away with a deal from Lori Greiner and generating $70 million in revenue.

From Farm to Glass

They’re just miles apart, but Capital Region wine regions are distinctively different based on their climate, terrain and soil

Each of our four wine regions has its own unique terroir, a French term describing the soil, climate and sunshine that give wines their distinct character. These winemakers want consumers to consider their wines farm-to-fork — that is, farm-to-glass.

Luscious Libations

Distilleries use local, natural flavors to enhance their creations

Whether in Sacramento or the upper climbs of the Gold Country, craft distillers are ready to give the drinking public a taste of all of the possibilities within libation.