When the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, residents desperately fled, many of them to Sacramento, which is now home to more than 10,000 Afghan refugees. As we now watch in horror at the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine, Comstock’s takes a look at how Afghan refugees are adjusting to their new life in Sacramento. – Judy Farah, editor

Zaki Rahain,

the Carmichael restaurant owner who was on a Taliban death list

Rahain worked with the U.S. government in Afghanistan

Zaki Rahain fires up the charcoal burners at his family’s little Afghan restaurant, Lapis Grill, in Carmichael and begins cooking skewers of chicken, lamb and beef. Half an hour later, the meats — a nearby slaughterhouse sets aside one cow and two lamb for the restaurant each week — accompanied by steaming rice plates, flatbreads and vegetables, are served up to diners.

Rahain’s family are ethnic Uzbeks from the town of Mazar-e Sharif. During the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan, Rahain, now 36, worked with the U.S. military in their counter-insurgency campaign to stop the Taliban regrouping. By 2013, he says, he was on a Taliban death list. “There was a bounty on my head,” he recalls. “If they caught me they would have decapitated me or skinned me alive,” he narrates in a strangely dispassionate tone. “I applied for asylum, a special immigrant visa.” Rahain left for California, went to college, married a woman he met in one of his classes and then, he states, was persuaded to return again to Afghanistan for another three years of work as a cultural adviser for U.S. Special Forces.

Only once it became clear that the Taliban was on the verge of regaining control over the entire country did Rahain permanently return to California, where he started working for the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, helping unaccompanied minor children. His family were left behind in Mazar-e Sharif, where they continued to run a small restaurant. Only as the Taliban took over — the fighters threatened to take Rahain’s 12-year-old sister as a “Taliban bride,” leading her to declare that she would kill herself rather than endure this fate — did they flee, ending up, like so many other internally displaced refugees, homeless on the streets of Kabul. They eventually were amongst the crowd at the airport desperately seeking spots on the airplanes that would fly thousands of refugees out of the country. The family didn’t get onto those planes but did manage to leave the country six months later, traveling through Iran, on to Brazil and finally for their reunion with Rahain in Sacramento.

Raihan’s parents and his siblings now live in Carmichael working to make the Lapis Grill and its accompanying food truck — which Rahain purchased from the savings he had set aside over the years — a success. They operate by word-of-mouth and keep things as simple as possible. There are no printed menus, but members of the Afghan community know that this is the place to come for authentic home cooking.

The family has run the restaurant for two years now, the walls laden with oil paintings, some portraying classic Afghan landscapes — including the now-destroyed Buddhist statues of Bamiyan — others showing Parisian street scenes. In one corner hangs a bird cage with a small white bird chirping away inside; nearby is a mounted deer’s head.

Zaki Rahain’s restaurant is a gathering point for Afghan artists, business figures, exiled political appointees and others. Some sit at tables; others sit cross legged on elevated platforms, their platters of food arrayed in front of them. But their clientele is no longer limited to Afghans. Nowadays, the owner says, smiling, a growing number of others also make the journey out to Carmichael to sample the charcoal-cooked meats; it even attracts Ukrainians, he explains, men and women who themselves had to also flee their home country in the face of aggression and now call Sacramento their home.

Aziz Tokhi,

the artist working with a new light

Afghan artist adjusts to a new life in Sacramento

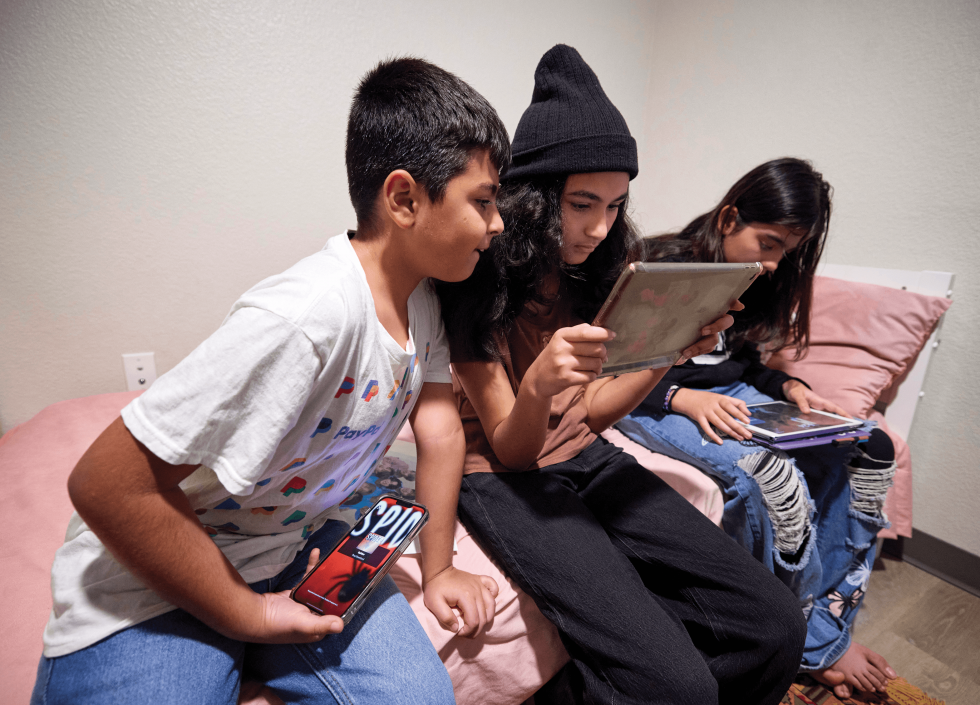

Aziz Tokhi’s daughter, Maryam, 14

In Afghanistan, before he left for California in 2019, Aziz Tokhi was an art professor at the University of Balkh. He specialized in watercolor plein air depictions of his country’s wild, mountainous scenery.

Now, here in Sacramento, he works for the city’s Fine Arts Center. Last September, he was also one of several local artists to contribute to an exhibition at the Mills Station Arts and Culture Center in Rancho Cordova, highlighting the stories and artwork of refugees.

Son Ali, 9; daughter Meena, 12; cousin Zinat Azimi, 12

“We’re trying to make here some community — Afghan culture, Afghan art, musicians, restaurants. I like it here. We appreciate the United States — to give us the visa to come here. They prepared some facilities after the war. My kids’ school, jobs. My wife is teaching in the San Juan Unified School District as an assistant teacher.”

It has, though, been a long journey, one sometimes jarring in its contrasts. “We have a different life than in Afghanistan,” he states. “Everything is different: language, culture. We started with zero life here. Everything, we left in Afghanistan.”

For Tokhi, despite the unfamiliarity of this new land, he finds his surroundings inspiring. He travels frequently and is particularly enamored of New Mexico and the peculiar qualities of its natural light. But he’s also happy closer to home. “Sacramento is beautiful,” he explains. “Especially, I like winter.”

Farzana Karimi,

the teacher who had high-profile jobs in Afghanistan

Now she helps Afghan students adapt to Capital Region classrooms

Aziz Tokhi’s wife Farzana Karimi and their three children, 14-year-old Maryam, 12-year-old Meena and 9-year-old Ali, are in the living room of their spacious apartment in a new complex one mile from the Arden Fair mall. They’ve recently come back from a winter trip to Lake Tahoe, and the kids are enthusiastically recapping their adventures in the snow.

In Afghanistan, Karimi, who has a degree in law and political science, worked a series of high-profile jobs with the Norwegian Refugee Council, the Electoral Complaints Commission and the U.S. Agency for International Development. She also spent time as a high school teacher in Balkh Province.

After she and her family were threatened by the Taliban, they managed to secure Special Immigrant Visas allowing them to resettle in the U.S. Since Karimi already had a sister living in Sacramento, and several of her erstwhile colleagues had made the move to California, they decided to head this way too.

At first, things were hard, but over time life has gotten easier. “We think it’s a very different city from those in Afghanistan. I felt my English is not good. After one week, I started going to Highland ESL class, and then I got a job as a cashier. Then I start working with the California Mobility Center as a coach. Then after that, I started, after more than one year, as a bilingual instructional assistant in the San Juan Unified School District. They need bilingual assistants in Dari and Farsi and Pashto. My language is Farsi.”

SJUSD has hundreds of Afghan students and an active program to provide services to help these new arrivals thrive. Karimi is one of several bilingual hires who work in the classrooms with the children as they learn English and familiarize themselves with American customs.

Now, with both Aziz and Karimi working, the family has time and money for vacations, extracurricular activities for the children, entertainment or, in 14-year-old Maryam’s case, hanging out with friends at the mall. Life is good in the U.S., Maryam thinks, but she still misses parts of her old world: “Friends, my family. A drink called Paradise — a drink with different kinds of fruit.” She misses the single-sex schooling that was the norm in Afghanistan before the Taliban reclaimed power and banned girls from attending school beyond sixth grade, though she doesn’t miss the corporal punishments that were routinely inflicted on wayward students.

For Karimi, American education opens the doors for all her children, the girls as well as her son, to excel and to live their dreams. “I hope all three of them get a good education — become a doctor, an engineer, a lawyer. I’m working for their future; always, I encourage them to learn. Here is a lot of opportunity for us. We are safe, nothing like Afghanistan. Everyone has the same rights, equality, here. We are happy. Here is my home.”

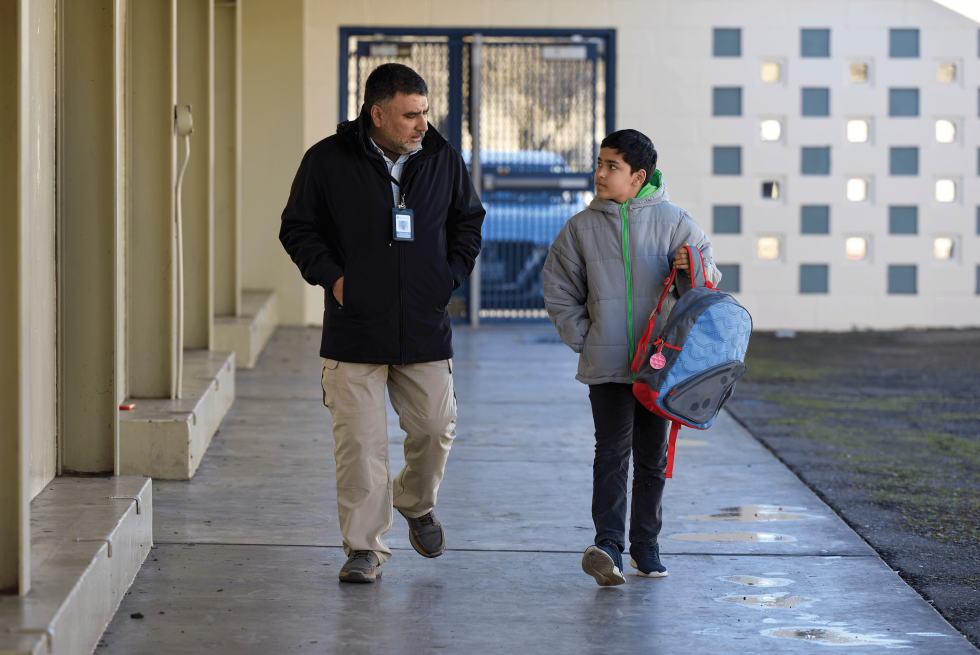

Abdul Basir,

the lawyer now helping fellow Afghans resettle in Sacramento

He teaches them English and how to navigate life in America

In early August 2021, Abdul Basir, then in his mid-40s, was attending a development conference in Lebanon. When the Afghan government suddenly collapsed in the face of a Taliban advance on Kabul, Basir found himself stranded. It was impossible to return to Afghanistan — there were no flights into the country — and he could only hope that his wife and teenage son would be able to find their own way to safety.

Basir had a crucial advantage over many of the other Afghans suddenly stranded by the Taliban’s takeover. He had already lived for three months in the United States once before, back in 2017, and had a green card. Because of that, he was able to rapidly secure the visa that he would need to start a life of exile. Within days, he was living in Sacramento, where many of his former colleagues had also chosen to settle, and where, he had heard, there were good Afghan restaurants and mosques catering to Afghan worshippers. He began studying for a driver’s permit and surfing YouTube videos to learn how to present himself when going for a U.S. job interview. He was also working to secure his family’s exit from the Taliban-controlled country. A few months later, they would manage to leave Afghanistan and join him at his new home in the Arden-Arcade area.

It wasn’t the first time that Basir had to start afresh.

As a child growing up in the shadow of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, Basir was excluded from the classroom. His village was repeatedly bombed and the schools shuttered. Basir missed his first several grades of schooling.

In the mid-1980s, when he was 9 or 10 years old, Basir’s family fled across the border into Pakistan, settling in one of the many refugee camps that, cumulatively, housed millions of exiled Afghans. In Peshawar, he finally managed to find a school, and his educational journey began.

When the Soviet-backed regime collapsed, the family returned to Afghanistan, and from there, Basir went to Egypt on a scholarship to study comparative law, looking at the interplay between Islamic and secular court systems. His degree served him in good stead. After the U.S.-backed coalition drove the Taliban from power in 2001, he would work for a series of U.S. Agency for International Development-backed projects, helping to build up the country’s legal institutions, including its Supreme Court, and creating a number of legal clinics. In 2018, he began working for the United Nations Development Project as a strategic adviser to the Independent Election Commission.

Now, all of the skills he had honed in Afghanistan would prove useful as he started his new life in Sacramento. Basir got a job with the River City Food Bank, working mainly with recent arrivals from Afghanistan. Then he got work at an Apple warehouse repairing phones. Finally, he heard that the San Juan Unified School District, which had seen an influx of hundreds of Afghan students, was looking for bilingual community resource assistants who could serve as community liaisons. He applied and soon afterwards found himself employed by the school district, first at Katherine Johnson Middle School, then at Rio Americano High School, and finally back at the middle school again. He would help students who were struggling with the English language, explain what their teachers and counselors were asking of them, help parents during meetings at the schools and lay out to the high school students what they needed to do in order to graduate.

Basir’s main job, he said, “is making bridges between the community and the school. When I see the newcomers arriving, they are totally unfamiliar with the educational system here in the U.S. They have many questions,” on everything from free school lunches to how to use the public transport system to where prayer spaces can be found.

It has become more than simply a paycheck, something more akin to a life passion. “Both in Afghanistan and here, my goal was, beside making money for my living, I should have a mission to help others,” he explains. “This is an area I can help the students and the community more and more. I feel I am useful to the community here.”

Comstock’s photographer Fred Greaves traveled to Afghanistan 14 times, along with visits to many other hotspots in the world, working with the USO (United Service Organizations), documenting their work supporting U.S. service members abroad.

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

The Evolution of Aesthetics

Women and men have a variety of ways to look their best in the Capital Region

When it comes to “having a little work done,” it’s all about perception. “I was actually one of those people who thought they would never do Botox in their life,” says Shawna Chrisman, nurse practitioner and founder of Destination Aesthetics. “I just wanted to age gracefully.” But a product called Lattise — which she calls her “gateway” — changed her perspective on what that means.

Residential Renaissance

New affordable apartment complexes offer appealing amenities such rooftop terraces, courtyards and shared community spaces

Some of the most exciting architecture being designed and built in the Capital Region today is multifamily residential. Attractive, amenity-rich condominiums, apartments and duplexes are popping up everywhere, proving that single-family luxury homes aren’t the only drool-worthy dwellings on the real estate market.

The Delta in Decline

Wildlife and businesses in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta are suffering from lack of fresh water

The life cycle of a salmon, so the story goes, is a heroic journey. The fish emerge from fertilized eggs in a river bed, swim to the ocean where they spend most of their lives and return to give birth in the exact place where they were born.

What’s Ahead for the Region’s Economy in 2024

Positive news, though risks abound

Those who forecast the direction of the U.S. economy have their eyes on empty office buildings. In September, two commercial real estate experts predicted that the vacant space resulting from work-from-home policies will put banks at risk and collapse tax revenues for large and mid-size cities around the country.

‘Mystery City’ Unveiled

Proposed community envisions the good ol’ days; critics call it sprawl

Sramek, 36, is founder and CEO of California Forever, which seeks to build a large new community in Solano County. While cities or large unincorporated communities have been built from scratch before in California and elsewhere, what makes this potential metropolis unusual — and has stirred public controversy — are the people behind it and its backstory.

The Bosch Boom

Bosch’s acquisition of TSI Semiconductors in Roseville is expected to significantly impact the region’s economy, workforce and educational institutions

In August 2023, Bosch acquired TSI with the intention of producing silicon carbide chips, a major element in the production of electric vehicles. Bosch is betting that the global demand for silicon carbide chips will continue to grow and intends to invest $1.5 billion in the new fabrication.