Sacramento is on track to get a dedicated makerspace for food entrepreneurs who want to launch and scale their brands, from home picklers to amateur charcutiers. A partnership with the San Francisco-based sustainable development firm Equity Community Builders and the Sacramento Department of Economic Development is bringing The Food Factory, a proposed commercial kitchen and food business incubator in the Alkali Flat neighborhood, closer to opening its doors by 2020.

“Having a space like this is critical to get your business off the ground to begin with, and to keep it sustainable,” says Sacramento-born restaurateur and developer Andrea Lepore, who is spearheading the project with site-owner Skip Rosenbloom. Lepore owns the pizzeria Hot Italian with branches in Midtown and Emeryville, as well as the firm Lepore Development. In the new partnership, Equity Community Builders will become Lepore’s co-developer, and the Department of Economic Development will help her build a financial strategy — welcome help for a project that has been in the works for nearly three years.

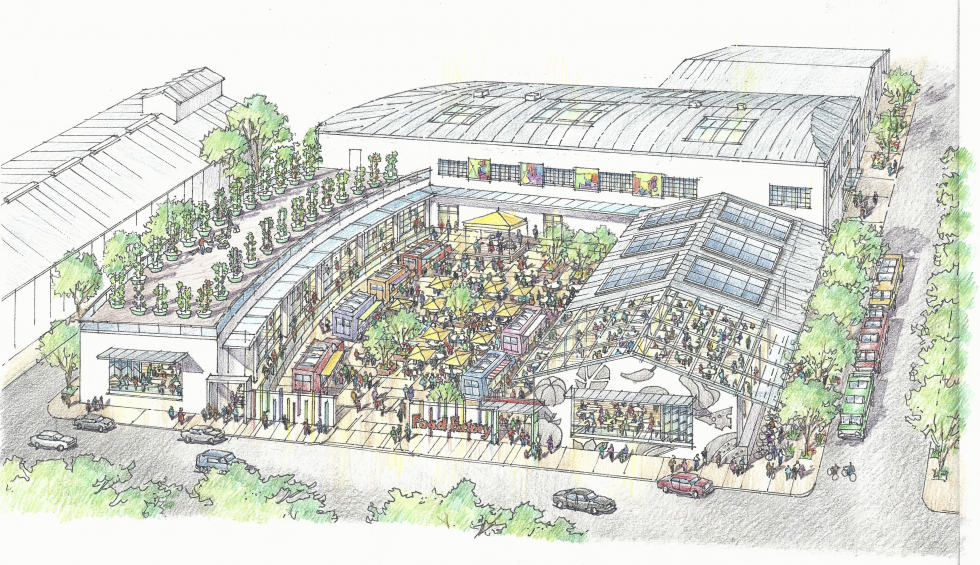

A rendering of The Food Factory, which is projected to open by

2020. (Rendering courtesy Andrea Lepore)

The seeds for The Food Factory were sown in 2015, when Lepore presented a master’s thesis in sustainable design at Boston Architectural College. Her project envisioned an environmentally friendly, aesthetically appealing commercial kitchen, patterned after not-for-profit models like Boston’s Commonwealth Kitchen. After meeting Rosenbloom through a mutual friend and touring the 35,000-square-foot industrial block he has owned since 2012, she knew she had found the perfect place to bring her thesis to life.

Sacramento is an ideal location for a food business incubator, says Lepore, noting the city’s proximity to farms, food scientists at UC Davis and food policy makers at the Capitol. The city also currently lacks options for entrepreneurs who want to grow out of the Cottage Food Law, which allows small producers to sell food they cook in their homes — as long as they make less than $50,000 in gross annual revenue. Anything that earns more must be made in a commercial kitchen. “It’s a great thing, and definitely somewhere to start,” Lepore says of the law, “but it’s not really designed for businesses that plan to scale.”

Lepore already has interest from several potential tenants who use the Cottage Food Law to produce, including Karla McNeil-Rueda and Eddie Houston of Cru Chocolate. “While the Cottage Food law is really great and we wouldn’t be where we are without it, there are some aspects of it that are impeding to a growing business,” says McNeil-Rueda. She cites the law’s income cap and its rules against selling online as impediments she could bypass with a commercial kitchen space.

Related: How the Entrepreneurs Behind Cru Chocolate Built their Cottage Food Business

As a first-generation American, McNeil-Rueda is especially enthusiastic about The Food Factory’s potential as an educational platform. Lepore plans to hold workshops that introduce new food businesses to food safety regulations, which McNeil-Rueda says would be a valuable resource for recent immigrants. “It’s mainly immigrants who start food businesses, but food safety here is not the same as food safety in Central America, for example,” she says. “At The Food Factory they can get the information they need to start.”

Shermain Hardesty, lecturer emerita of agricultural economics at UC Davis, agrees that commercial kitchens like The Food Factory are key to the success of small food businesses. “I always get excited about projects like these,” she says. In her two decades teaching small producers how to build their brands, Hardesty has seen several similar projects flower and fade in the counties surrounding Sacramento, due to issues like insufficient funding or difficult-to-access locations. She nevertheless believes that the concept could work in the city proper, thanks to the density of the urban population and its growing interest in farm-to-table food.

Ryan Seng, owner of the beverage company Can Can Cocktails, is more hesitant to bet on the success of the project. In early 2018, Seng moved his operations from a contract kitchen in Old Tavern Distillery to a unit in Rosenbloom’s industrial block, a few doors down from the space that will become The Food Factory. He was initially interested in partnering with or being part of The Food Factory, but he began manufacturing long before the commercial kitchen project could get off the ground.

“It’s a cool space, and I love the neighborhood,” he says, “but there are big improvements that need to be made. We’re talking millions of dollars.” He notes that the block is not currently outfitted for food and beverage manufacturing, which required him to install expensive features like floor drains when he moved his operations there in early 2018. He suggests that a “bigger tenant” — someone with money and concrete plans — could help supply the capital necessary to pay for building the kitchen, installing safety features, and other big improvements.

Lepore, however, prefers to focus on emerging entrepreneurs, who she sees as key to city’s economic development. “It’s all about creating businesses and jobs, but food businesses are not like tech businesses. You can’t start them in a little room,” she says, conjuring the mythos of brands like Apple and Amazon that began in garages.

In the interest of those entrepreneurs, The Food Factory will offer more than mere equipment in its member packages, which will start at around $500 per month. Lepore plans to organize workshops on key skills like marketing and branding that flavor-focused producers might overlook. A retail store will display members’ finished products and help them reach their first consumers. To attract those consumers, The Food Factory will host events for the public that feature members’ products as well as music and other entertainment.

Though Lepore predicts that The Food Factory is still two years away from opening, the project is moving steadily forward. A $25,000 Creative Economy Pilot Project grant from the City of Sacramento paid for floor plans and 3D renderings, which helped bring on board Equity Community Builders, a developer that works with nonprofits like The Boys and Girls Club, the American Conservatory Theatre and the Tides Foundation. The building, emblazoned by a mural by local street artist Anthony Padilla, immediately announces itself as the future site of The Food Factory.

Completed in August 2017 as a collaboration with California Endowment, Padilla’s mural features against a raised fist — a universal symbol of solidarity, albeit here clutching a bunch of beets — against a rainbow of floating tomatoes. The message reflects what Lepore says is the most valuable benefit of The Food Factory.

“Here, you’re part of a community with people who are experiencing the same things that you’re going through,” she says. “You help each other and collaborate. That’s what an incubator really is.”

Comments

We love to be a part of this

We love to be a part of this