Andrew and Krista Abrahams wanted to rethink the assumptions of traditional dairy production. What began as an inquiry into the source of their food and a desire to connect consumers with ethically produced animal proteins and fats changed the course of their lives.

The more they learned about practices used to produce milk commercially, Andrew Abrahams says they thought maybe they needed to do this themselves. They decided on California for their dairy’s destination for its optimal weather and to be closer to family and a startup Abrahams was involved with at the time.

In 2011, after leaving New York City, the couple set down roots in rural Lincoln’s rolling foothills and opened Long Dream Farm. The California Department of Food and Agriculture-certified dairy and creamery is one of only two dairies in Placer County, according to the county’s agriculture department. The nonprofit farm is distinguished by its unconventional business model: “Dairy re-thought from the cow’s perspective.”

At conventional dairies, milk cows are commodities. They’re artificially inseminated every year to produce a continuous milk supply and separated from their calves within hours of birth, which a growing population is opposing for animal welfare rights. The cows are mechanically milked on average 2-3 times a day, producing more than six times what their bodies are designed for, and when milk production slows, dairy cows are sold to the meat industry for food.

The veal industry — a byproduct of the dairy industry — consists of male calves, which are considered unsuitable for beef production when they are full-grown. The calves are crated and immobilized for several months to inhibit muscle development for more tender cuts of meat, though veal crates have been banned as unethical confinement by several states, including California, which passed its ban in 2008 under Proposition 2 that took effect in 2015.

Long Dream Farm set out to prove that dairy products could be produced economically and ethically, placing animals’ rights, natural behaviors and well-being above production. It blends traditional practices of small dairies when they were cornerstones of rural communities with innovative practices, including detaching the dairy from the meat industry, preserving familial herds on the farm, providing lifelong care for animals in food production and supporting stewardship of the land.

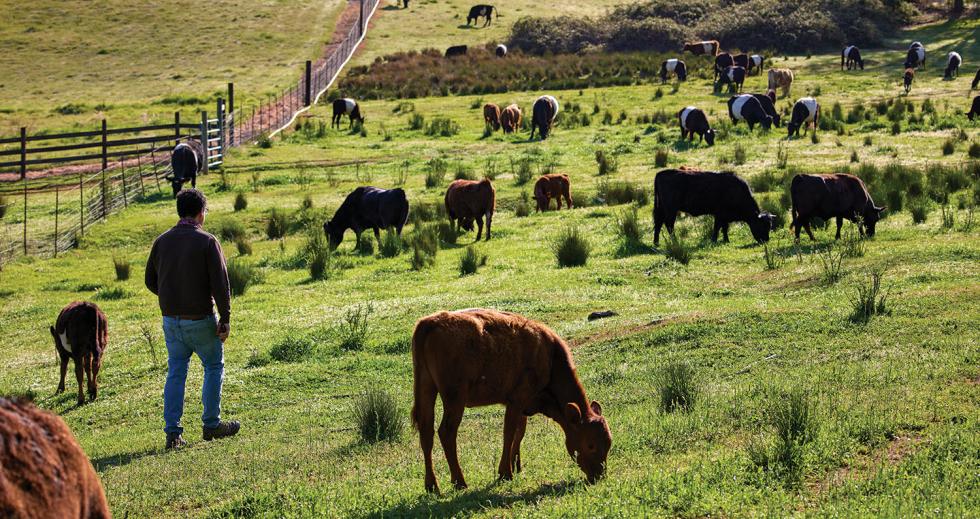

Ninety acres of the 700-acre property are devoted to the working farm, where generations of cows spend their days together grazing irrigated, rolling pastures and resting under the shade of mature oak trees. Calves nurse until they naturally wean, and bulls are kept together in their own family group. Of roughly 200 cattle, about 60 are milking cows. Only 25-30 are milked at one time, on average, in the morning (with several days off), and they’re bred naturally every 2-3 years. The animals at Long Dream Farm will live out their lives on the farm’s permanent sanctuary.

Andrew and Krista Abrahams opened Long Dream Farm in Lincoln in

2011. The 90-acre farm is one of two dairies in Placer County.

But the economics of a slaughter-free dairy are a work in progress. “That’s why we call it an experiment, because we’re trying to discover how to do this,” says Abrahams. “It’s not as economically successful as we might like, but we mainly want to prove that it (is) possible to do it.”

Long Dream Farm prices its products — all produced on-site — at what it considers to be comparable to similar products at Whole Foods Market produced by methods that don’t use their practices. For example, 9-11 ounces of halloumi-style cheese sells for $9.50, 8 ounces of butter is $8.25, a quart of Greek-style yogurt is $9 and 14 ounces of ice cream is $8.25 in the farm’s online store.

“For what they’re doing, their prices are very, very fair,” says Susie Sutphin, founder and director of Tahoe Food Hub, a nonprofit in Truckee that connects local farmers with local markets and has sold Long Dream Farm products for the past four years. It has seen a steady increase in sales of the farm’s products. “People think if a product’s organic and pasture raised, that’s as good as it gets,” says Sutphin. “They don’t realize it can be even better than that. That’s why what Long Dream Farm is doing is so revolutionary.”

While the farm’s production cycles are dependent on demand and other factors, such as what the cows are eating, Abrahams says if they put all production into a single product, they could produce roughly 600 pounds of yogurt, 300 pounds of cheese or 100 pounds of butter a week. The milk cows at Long Dream Farm each produce about 6,000-10,000 pounds of milk annually to produce dairy products. That’s within the range of what commercial dairy cows produced 50 years ago. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the average dairy cow in the U.S. produced 9,751 pounds of milk in 1970. That average shot up to 23,391 pounds of milk per cow in 2019.

Nearly 30 percent of Long Dream Farm’s products are donated, primarily to Auburn Interfaith Food Closet. The remaining products are sold to the Tahoe Food Hub, individual customers and through its online market.

Long Dream Farm’s products are priced competitively with similar

products from Whole Foods Market.

Under its current model, which includes charitable giving, the farm would have to raise its prices one-and-a-half to two times to break even. However, if it only produced its most profitable products and sold its entire production, Long Dream Farm could break even at its current prices, says Abrahams.

Rather than increasing the price of products — which are designed to promote the farm’s practices rather than the products themselves — Long Dream Farm established a nonprofit arm in 2019. All revenue from the dairy goes to the nonprofit, which helps fund the sanctuary. Abrahams says there was so much interest in what the farm was doing, people wanted to be able to make tax-deductible donations.

Abrahams believes their knowledge and experience could serve as the basis for a viable model for startup dairies, in addition to the required capital and land. And with a combination of selecting particular breeds and characteristics that produce longer lactations, breeding and the number of animals requiring lifetime sanctuary is reduced. “Then the economics could become very different,” he says.

But that requires a consumer base that cares about animal welfare and environmental stewardship in food production. To promote advocacy and education, tours of the farm and overnight stays are open to the public (after temporarily closing due to the pandemic), and the Abrahams serve as a resource for those interested in replicating their model.

Abrahams hopes Long Dream Farm products will appeal to vegans who choose the lifestyle for animal welfare issues and believes their dairy and sanctuary model can fund operations that serve as a solution for what he anticipates will be a need for lifetime sanctuary for animals in dairy and meat production as the market for plant-based alternatives grows. In 2019, the alternative-milk market grew 5 percent to $2 billion in sales, capturing 14 percent of the milk market while dairy milk sales grew only by 0.1 percent, according to the Plant Based Foods Association.

Notably, that market shift is putting pressure on the dairy industry. Dean Foods, the largest U.S. milk producer, filed for bankruptcy in 2019, citing a decrease in demand for cow’s milk as demand for plant-based milk grows, according to CNN.

Abrahams says efforts to reach the vegan community have not always been pleasant. “We have some defenders, but it kind of feels like it’s 10-to-1 against us,” he says.

A fundamental belief among many individuals who choose a vegan lifestyle based on animal rights and welfare is that animals should not be part of humans’ food production system in any way. Abrahams says vegans who oppose his model have argued the animals are still being exploited because no one knows what the animals want. “I would disagree with that statement,” he says. “I really think we do know. It’s not obvious perhaps, but (when) you spend time with the animal and you treat them like they’re your friends, you kind of do.”

Martha Sanchez of Santa Ana, who chose a vegan lifestyle in 2016 for animal welfare issues, noticed a negative change in her health after a year. She didn’t want to go back to buying conventional animal protein because it went against her beliefs, so she spent nearly a year researching ethically produced animal products, she says, and found Long Dream Farm.

“They exceeded my expectations of what I was looking for, but in reality, they should be the standard,” says Sanchez, who visited the farm in 2017 for her birthday to see how the animals were treated. “I wish that more establishments and farms, whether they’re big or small, would function like this because all parties win.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Regenerating Our Soil

A shift in agriculture practices can help the environment — and the bottom line

The dialogue around regenerative agriculture has evolved over the last decade as agricultural methods that were once practiced by Indigenous communities around the world are reemerging.

A Blend for Success

Wineries in the Capital Region have added an array of amenities to keep oenophiles closer to home

With daytrip-worthy destinations in the Capital Region, wine enthusiasts no longer need to pay the higher prices and drive to Napa to get a world-class winery experience.

Off the Beaten Track: A Return to Roots

Award-winning Suisun Valley winemaker continues her family's legacy

The Tolenas Winery label produces a variety of wines, but what sets it apart is the white pinot noir Eclipse that took a gold medal at the 2019 International Women’s Wine Competition.

Flour Power

Long-term wheat research undertaken by UC Davis combats food insecurity

A 20-year study led by a UC Davis scientist and his

colleague at the University of Haifa in Israel was

recently recognized by the U.S.-Israel Binational Agricultural

Research and Development Fund.