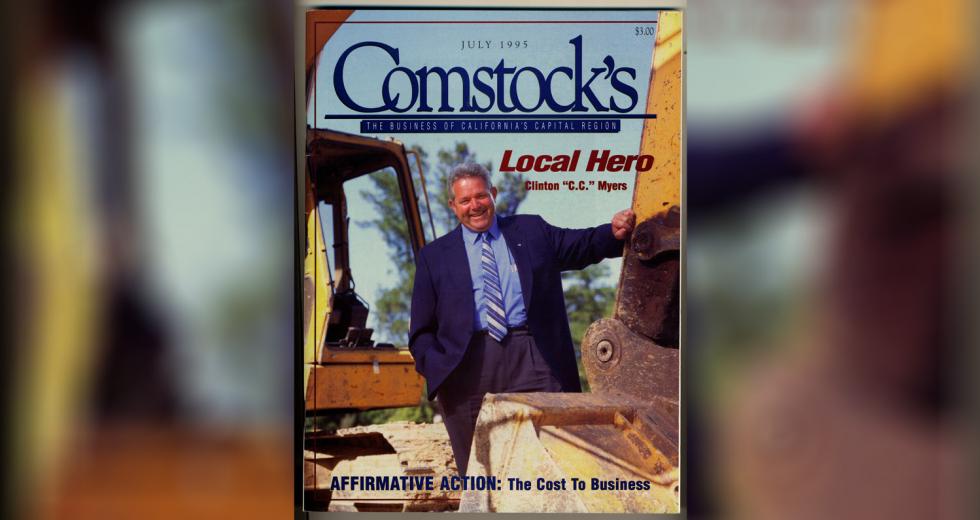

Clinton “C.C.” Myers has been a hero at least three times during his life. The Rancho Cordova builder says he has built or rebuilt 1,000 bridges, but his company’s speed and efficiency in rebuilding three bridges devastated by natural disasters in the past five years has won him national acclaim. In 55 days — less than the time it ordinarily takes to build one bridge in California — Myers rebuilt two bridges in Watsonville after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. He reconstructed the Santa Monica Freeway after the 1994 Northridge earthquake in just 66 days; and rebuilt the 1995 flood-stricken Interstate 5 span near Coalinga in 21 days. (A project such as the Coalinga bridge usually takes about six months to complete.)

Such efficiency has its rewards: C.C. Myers, Inc. earned a $14.8 million bonus from the State of California for the quick-fix of the Santa Monica Freeway. Given the importance of that vital artery, it was money well spent. The January 1994 earthquake that shattered Los Angeles crumbled the freeway which is regarded as the busiest in the world. Ordinarily, the Santa Monica Freeway handles more than 350,000 vehicles per day between downtown Los Angeles and Santa Monica. Its closure was crippling the city.

Analysis by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) showed that the damage cost the California economy more than $1 million each day the freeway remained closed. The rush to restore the freeway was spurred by a 180 day window within which the federal government would pick up the entire tab, standard for natural disasters.

Eighteen days after the January 17th ‘quake, Caltrans selected Myers’s company for the job of rebuilding the freeway. The company was the second-lowest of five invited bidders; bids were submitted based on a formula that considered both time and money needed to complete the project. A bid from Fontana-based Brutoco Engineering & Construction came in first with a promise to do the job in 100 days for $20 million, but the company withdrew when an error was discovered on its application.

Myers agreed to do the job in 140 days for $14.9 million. Caltrans offered a bonus of $200,000 per day for each day the freeway was open before 140 days, and a matching penalty for every day the job ran over the 140 days. Since Myers completed the job 74 days early, the $14.8 million bonus almost equalled the $14.9 million basic fee for the job.

No time was wasted in meeting the tight schedule. Within 24 hours of being awarded the contract, Myers was dispatching crews from his office in Gardena, about 25 miles from the freeway site. He and 22 supervisors from his Northern California operation went to Southern California, where he hired the rest of the carpenters, ironworkers and other contractors from the Los Angeles area. Myers was a constant presence at the job site night and day, coordinating the operation, resolving on-site problems immediately and directing the work crews like a general overseeing a military offensive.

“It was like building a new company,” says Myers. “We spent the money right there in the local area, hiring people who basically were suffering from the disaster. We ran crews 24 hours a day, seven days a week, paying an average of $50 per hour. Our labor ran over $1 million per week.”

The relationship between a general contractor and its subcontractors can be thorny, but Myers took steps to ensure a cooperative effort even before he won the bid. “Prior to the invitation to bid, we called the subs we’d like to quote on the work and told them we expected to work seven days a week, around the clock if necessary to meet the schedule,” Myers says. Once the bid was awarded, Myers met with the subs and presented the schedule. He attributes their willingness to cooperate in part to the urgency of the situation and in part to “our reputation in how we treat subcontractors. Our theory is to treat them fairly, pay timely and do what you tell them you’re going to do.”

As an example of the extraordinary cooperation that took place in the project, he points to the re-enforced steel workers. The subcontractor selected for the job had only 15 qualified steel workers, which Myers knew going into “I needed 128 people, so I went to their competitors and asked for help. They said, ‘I don’t want to help that guy.’ I told them, ‘You’re helping me.’ They said, ‘How many do you need?’ I asked, “How many have you got? I need them all.’ They supported me in this because they knew I’ve treated them right over the years.”

Since most of the labor was union, Myers met immediately with all the locals, arranging for two 12 hour shifts, plus overtime. “We asked the unions for support and they all gave 100 percent support,” he says. ‘They did things for us that they normally don’t do. We didn’t have any grievances on that job — the unions were part of the team; so were the suppliers.”

History had convinced Myers that he could complete the Santa Monica Freeway project in 100 days. Following the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, his company rebuilt two damaged bridges on Highway 1 near Watsonville 45 days ahead of schedule, despite winter rains and the Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year holidays. Caltrans had allotted 100 days for the project, with a $30,000 per day, first-of-its-kind cash incentive to complete the project sooner.

About a year after completing the Santa Monica Freeway, Myers won the contract to reconstruct the twin 1-5 bridges washed out over the Arroyo Pasajero in Fresno County near Coalinga. The lowest of four bidders, Myers was to be paid $3,645,772 if the job was completed in 50 days. The contract included a bonus of $30,000 a day for early completion and matching penalties if the job took longer. In just 21 days, the new bridge was finished and strong enough to permit peak river flows of 40,000 cubic feet per second — 10,000 more than the estimated peak flow during the March 10th washout. Myers collected his $3.6 million, with an additional $870,000 bonus.

The emergency conditions under which Myers delivered these projects meant that Caltrans was willing to relax and overlook some of its normal procedures. This flexibility contributed to the projects’ prompt delivery. Under normal circumstances, a set of bridge plans is sent to Caltrans headquarters where they are evaluated for a period of weeks or even months, depending upon the magnitude of the job. The plans are then submitted for peer review and finally handed over to the builder.

The Loma Prieta earthquake spawned special legislation that cuts through all of the red tape involved in rebuilding disaster-stricken roadways and bridges. Under these “emergency contracts,” the state immediately goes to work designing and writing specifications for the project, then selects qualified contractors to bid on projects. The bids are then evaluated and the contract is awarded to the lowest bidder.

“Sometimes the state spends more money on red tape than it costs to complete the entire job,” said Myers. “For example, the Cypress Freeway [in Oakland] has taken all this time to get all the environmental stuff cleared. It has cost the state over $100 million, and we pay for that.”

Goal-driven Myers loses his jovial manners when the topic of conversation turns to government red tape. He’s livid over the bureaucratic entanglements brought upon the building industry by narrowly focused and ill-coordinated government agencies at municipal, regional, state and federal levels, imposing often arcane and punitive regulations. “Our government is more worried about the people who don’t work than those who do,” says an annoyed Myers. ‘Take for example this Fairy Shrimp thing. That’s going to hurt California worse than 10 L.A. earthquakes.”

Myers sees at least two steps the state could take to improve the quality of its public works projects while also reducing their cost. One is to make incentives a part of normal, non-emergency contracts — especially for projects in high traffic areas to diminish the amount of time work crews are exposed to potential accidents.

“’The state charges a penalty for every day we’re short. Why shouldn’t I get an incentive for every day I’m early? It should go both ways,” says Myers. He adds that bringing a project in early is simply “a matter of scheduling and math. If I get the job done one week early, that’s one week of payroll that the state doesn’t have to cover.” With incentives in every contract, “everybody’d be more concerned about meeting their schedule,” Myers says. “Sure, it hurts the weak ones who can’t schedule. But it can be done right.”

The other way the state could achieve a better, less expensive public works project is summed up in two words, “design/build.” Myers strongly asserts that the “Department of Transportation does an excellent job — its only problem is the politicians making decisions. One downfall is there’s not enough people [at Caltrans] to design the projects, so they go to outside firms when they’re overloaded.”

Rather than simply hiring outside engineers to design projects that the state then bids to contractors, Myers suggests that Caltrans should contract with an outside firm to design and build the project. “We’d hire the same outside engineers the state would hire, but we’d control them and make sure the state gets the design that’s the cheapest and most cost effective to build,” Myers explains. ‘That would stretch the dollars 15 to 20 percent further overall. That’s 15 to 20 percent more work you could do for the same amount of money. I think I proved that in Santa Monica, which was design/build. There were no change orders, not one [liability] claim. When I gave a price, that was the price.”

Fame and fortune didn’t happen overnight for Myers, who was described by Rush Limbaugh as the New American Hero. The second oldest of 13 children, Myers was raised on a hard-scrabble farm in Highland, San Bernardino County. At 8 years of age, he was plowing, weeding and irrigating fields when he wasn’t busy harvesting, washing and packaging vegetables for market. Every morning his father would take the kids to school on his way to market; after school, he was there waiting to pick them up for another round of farm work.

Myers, who stands 6-foot-4, tugs at the paisley suspenders harnessing his striped shirt as he recalls those days. “We had to do that seven days a week,” he says. “It was always a big deal on Sunday to have a chicken dinner and spend about two to three hours having a water fight or just goofing around before going back to the fields.”

After completing the 10th grade, Myers bought his first car by picking up redeemable pop bottles and saving pennies. That same year, he drove to Long Beach and got his first construction job as a carpenter’s apprentice, eventually working for Los Angeles bridge builder Polich & Benedict Inc. At 27 years of age, he was named to manage the company’s age Northern California operation. “I ran the business all by myself — all of Fresno, Sacramento and the Bay Area. I’d see the bosses only once or twice a year,” says Myers. “We made money on every job we ever did. The only reason I quit is because they didn’t pay my people right.”

Myers is a strong believer in rewarding people for their efforts, both financially and by making them feel a part of the team. After Polich & Benedict fold- ed, Myers started his own company, taking with him one of the partners. When the older man retired, Myers threw him a party at the Rancho Cordova Sheraton and handed him the keys to a new Rolls Royce. More recently, the supervisors who worked on the Santa Monica Freeway received a $1,000 bonus each week, were put up in hotels and allowed to bring their wives with them if they wanted to.

The Santa Monica Freeway project brought Myers and his company worldwide recognition and many honors and awards. Myers proudly plays a videotape of a personal message delivered by Gov. Wilson that began, “You’re the miracle worker of the Santa Monica Freeway. ” The Associated General Contractors of California presented Myers with the prestigious 1995 Constructor Award for his company’s “contribution to the community” and for “meeting the challenge of the difficult job — heavy engineering.” The Los Angeles City Council delivered a Resolution of Appreciation from the Residents of Los Angeles for both the Santa Monica Freeway and 1-5 bridge projects.

Although he made his fortune in the construction industry, Myers owns 26 different businesses ranging from real estate developments to oil and gas wells in Oklahoma and a casino in Eastern Europe. One of his latest capital ventures is Snap Tite, a fiberglass composite jacket that, when adhered to bridge columns, increases their strength by up to 300 percent. Norman C. Fawley, the product’s inventor, formed a partnership with Myers shortly after repairs on the Santa Monica Freeway had been completed.

At about 60 pounds apiece, Snap Tite jackets are light enough to be carried by two workers and can be installed on a concrete column in hours rather than days as is the case with heavy and bulky steel reinforcements. This flexibility results in significant savings of time and money. The technology is being further tested at the University of Southern California by engineer Yan Xiao, who helped develop the steel jacket system more than a decade ago.

“I see the market for Snap Tite being on the East Coast and other areas where bridge deterioration due to saltwater or weather is a big factor,” says Myers. “We’re also looking at using the product to reinforce parking structures and buildings.” He expects to be manufacturing Snap Tite jackets in about six months, but he says the manufacturing facility most likely will be built in another state — “in a city that would love to have us and will give us tax benefits,” he adds.

As much as Myers loves making deals and building his empire, he enjoys family life. He, his wife Janelle and their two teenage sons spend a lot of time at their Lake Tahoe home, which is equipped with a heliport and a mooring for their speed boat. He also has two daughters in their 30s from his previous marriage.

“Building bridges came absolutely natural to me,” says Myers. “l found my niche at a very young age, whereas a lot of people find it later in life and some people never do find it.”

—

This story originally ran in the July 1995 issue of Comstock’s magazine. In recognition of the magazine’s 30th anniversary, the article was reproduced online exactly as it appeared in print.

Recommended For You

Still Going Strong: Catching Up with C.C. Myers

C.C. Myers was lauded for “working miracles in heavy construction.” A project in Santa Monica brought Myers and his company worldwide recognition and many honors and awards as well as a spot on the cover of the July 1995 issue of Comstock’s magazine.