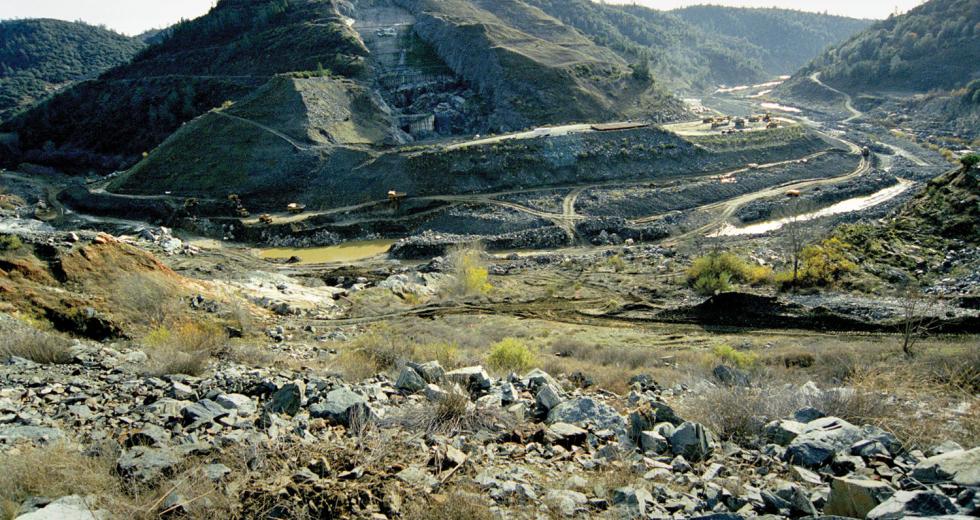

More than four decades after it was proposed, the Auburn dam still draws conflicting opinions about why it was doomed. The proposal called for a dam on the north fork of the American River to be part of the Central Valley Project, the federal government’s water system in California. The project, designed in the 1960s, would have provided water storage, flood protection and hydro-electric power for the Sacramento region. In 1975, construction ended after eight years when an earthquake of magnitude 5.7 near the Oroville dam, 50 miles to the northwest, raised fears the same could happen in Auburn. The project has been mired in controversy since.

The project had hope until December, when the state Water Resources Control Board voted unanimously to revoke the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s water rights permits, citing California’s “use-it-or-lose-it” water law.

Why did the dam fail? Some say government ineptitude killed the dam. Others say federal reforms changed funding, making the dam too expensive. Still, others point to the earthquake fault that lies beneath the dam site or say the project was proposed at a time when the environmental movement was beginning to change people’s attitudes about altering nature.

In 1965, Congress authorized building the Auburn dam 40 miles northeast of Sacramento. Construction started two years later. The proposed 685-foot-tall, thin arch structure would have created a 2.3 million acre-foot reservoir to store water for agriculture, municipal and industrial uses. It would have recharged groundwater, provided regional flood protection, generated hydropower and offered recreation.

Ronald Stork, senior policy advocate with Friends of the River, fought against the dam for many years. He attributes its demise to former President Ronald Reagan’s fiscal reforms. Before Reagan, the U.S. government heavily subsidized budgets for federal water projects. Reagan’s reforms required water and power utilities to pay for the resources they received. A 2006 Bureau of Reclamation study showed the reservoir could yield an average 208,000 acre-feet of water per year, about half the amount originally planned. The dam’s cost-to-benefit ratio made little economic sense, Stork says. The Auburn dam wasn’t supported by the utilities and agencies that would have benefited from it. “It only made sense if the taxpayers … provided it as a gift to California,” he says.

Rep. Dan Lungren, whose district includes the Auburn area, says cost killed the project. The 2006 bureau study, commissioned by then-Rep. John Doolittle, found the project would cost an estimated $6 billion to $10 billion. That’s “more than twice the cost of earlier estimates,” according to the bureau.

Lungren still defends the dam as insurance for a flood-prone region and says opponents focused on the cost rather than potential flood-incurred losses. The Sacramento area needs 500-year flood protection, and the only way it can achieve it is with an Auburn dam, Lungren says. It now has 100-year flood protection, meaning a catastrophic flood has the probability of recurring once in 100 years. “Every estimate I have seen is that the consequence of a catastrophic event here would give us at least twice the losses in our area that they suffered in New Orleans,” Lungren says. “I find that unacceptable.”

Mel Lytle, water resource coordinator for San Joaquin County, says the county has been waiting to receive American River water since the 1950s, mostly for agriculture. The county has been reducing its groundwater basin 1 to 1.5 feet each year despite conservation measures.

The state and federal water projects never developed all the water supply they planned, he says, while the Central Valley Project diverted water that once flowed through San Joaquin County to other locations. An Auburn dam would have provided sufficient water storage, Lytle says. “It’s a shell game because they made contracts to provide water south (of Auburn), but there isn’t the water to fulfill those contracts,” he says.

Auburn’s dam was proposed at the end of the country’s dam-building era when most prime spots in California for water storage were taken. It was conceived as a 1950s approach to water, when the country’s natural resources policies fueled an economy based on principles of extraction. Dam supporters found themselves caught in a changing culture, says Gary Estes, a board member of Protect American River Canyons, an Auburn-based group that formed in the 1970s to stop the dam. Damming the river would have flooded 48 miles of river canyon, killing fish and denuding the banks, Estes says, and the American public was beginning to realize the detrimental effects of dams on the environment.

The region’s water leaders have found less expensive alternatives to flood protection and supply replenishment over the years, he says, which has made the Auburn dam irrelevant.

Recommended For You

Spending Water Like Money

When conservation alone can't solve the state's water problems

For many environmentalists and residents of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the solution to California’s water supply sounds brilliant in its simplicity: Use less than we do now, particularly in areas of the state that have precious little of their own to begin with, thereby eliminating the need for spending billions of dollars on new water storage. But don’t try selling that idea to the bulk of California’s most powerful water stakeholders, many of whom contend that all the low-flow toilets and drip irrigation systems in the world won’t mean much without more dams and reservoirs to capture water during wet years and reap the benefits in dry times.

Change of Plans

Regional conservation efforts battle dwindling budgets and staff

The future of community growth in the Capital Region hinges on the fate of several habitat conservation plans slogging through the development pipeline.