Stan Van Vleck achieved a lifelong dream when he acquired the family ranch in 2008 — only to be hit with the realization that the business might not survive. The Great Recession, a downturn in the global economy that year, made business tough. Even more troubling to Van Vleck was his sense that ranching alone would never be a successful venture.

According to Van Vleck and other Capital Region ranchers, the industry is characterized by tough economics. Ranching requires huge capital investments for land, cattle and other assets, while income from beef is inconsistent and barely enough to cover business costs and support a family.

Van Vleck thought he might have to sell the ranch in Rancho Murieta, which had been in the family since 1856. “I knew I’d be letting down my ancestors by quitting,” he says, adding that the ranch would have likely been converted into a residential subdivision.

Many ranchers are choosing to sell their land to developers and get out of the business. From 1984 to 2018, California lost about 425,000 acres of grazing land, the state Department of Conservation found in a review of the most recent statewide data. Most of the land was converted to “urban and built-up land.” Some Capital Region counties have seen major losses of ranchland. From 1998 to 2020, Sacramento County lost about 29,000 acres of grazing land, a 16 percent loss of all its ranchland, according to the state.

In that time, San Joaquin County lost about 32,000 acres, a 20 percent loss overall. San Joaquin and Sacramento counties saw increases in residential housing during that time, driven in part by an influx of coastal residents seeking cheaper housing, a trend that is expected to continue.

Ranching supporters worry about the loss of a California tradition. Ranching has been a central part of California’s economy and its cultural traditions since pre-statehood. Under Spanish and Mexican authority, ranchos were a common form of land grant. Ranching became more popular when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, and the Gold Rush created greater demand for beef.

The industry rose most prominently in the Central Valley, where vast stretches of open and relatively flat land provided good grazing. The industry was led by pioneers like Henry Miller, who owned more than a million acres in California and other western states, and Jack Harris, who founded Harris Ranch in 1937, the company that was once the state’s leading beef producer.

Established in 1856, the Van Vleck Ranch had to diversify

operations to continue operating, including opening up sales to

premium businesses such as the restaurant company that owns the

French Laundry in Yountville.

Ranching plays a major role in California’s nation-leading agricultural economy. More than a third of the state’s farmland is used for grazing, and cattle and calves were the state’s third-leading agricultural commodity in 2023. But ranchers are also susceptible to the same pressures felt by crop farmers. Drought means less water for grass, whether the grazing land is irrigated or not, and that means the land can support fewer cows. Regulations add costs for the care and transport of cattle.

Comstock’s spoke to Van Vleck and two other ranchers, Tim Lewis and Scott Stone, about what they have done to stay in ranching and why they continue to work in such a demanding industry.

Tim Lewis: Seven days a week, doing what he loves

Tim Lewis works all day, everyday, to keep his cattle ranching and transport business successful. He doesn’t mind because ranching is his passion. “If you’re doing what you love, you’ll never work a day in your life,” he says. His ranch, Tim Lewis Livestock, sits on 2,000 acres on Twin Cities Road in southeastern Sacramento County, in the shadow of the cooling towers of the decommissioned Rancho Seco nuclear power plant.

Many of Sacramento County’s remaining ranches are located in its southeastern corner, but suburban development is increasingly happening nearby, and would accelerate if a planned highway, the Capital Southeast Connector Project, is completed. The highway would be built along Grant Line Road, north of Lewis’ ranch.

Putting in long hours isn’t all Lewis has done to keep the business running. He also had to diversify. As CEO and president, Lewis is responsible for a company that raises and transports cows for beef production. He owns 1,400 head of cattle and five trucks for transporting his and other ranchers’ cows. He employs four cowboys and five truck drivers. He gets up before dawn every day when it is cooler and easier to work with the cows. “Everything we do is for the betterment of the animals,” he says.

Tim Lewis rides through his ranch in southern Sacramento County.

He says ranching keeps him working around the clock — and he

loves it.

Lewis grew up in a ranching family. His father owned and operated a ranch in Elk Grove near Lewis’ current ranch, and he grew up loving the work. He studied farming in college for a short time, but it only convinced him how much he loved ranching. He helped his father run his ranch and then took over when his father died, before eventually starting his own ranch.

Late each spring, Lewis has to move his cows to the northernmost part of California, near Alturas, where he leases grazing land. The higher elevation provides cooler weather and greener grass.

Regulations put strong demands on his work, he says. The federal government has strict requirements for raising beef. The state’s vehicle emissions requirements mean he has to replace trucks even though they still run.

Lewis says he sticks with it because he loves working with animals and being a part of the ranching tradition. He has had offers from developers to buy his land but never seriously considered them, he says.

“It is a very difficult business to raise a family on,” he says. “It’s a very harsh market.”

Stan Van Vleck: Expanding on a tradition

Like Lewis, Stan Van Vleck grew up in a ranching family and loved the work as a kid. He hoped to take over the family business when he finished getting a degree in agriculture from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. His father had other ideas.

Stan Van Vleck Sr. told his son that the ranch could not support two families. His older brother was already running the ranch. So the younger Van Vleck went to law school and worked as an attorney for many years at Downey Brand, one of Sacramento’s best-known law firms. But the desire to run the ranch never died, and when his father passed away in 2001 while piloting a helicopter that crashed over the ranch, he started managing the ranch and putting together a plan to buy out his siblings and become full owner of the ranch in Rancho Murieta next to the Jackson Highway.

“I knew I’d be letting down my ancestors by quitting.”

Stan Van Vleck, rancher

Once he bought the ranch in 2008, he expanded the business to include premium sales and not just selling cows at auction. The ranch’s clients include Michael Mina, a celebrity chef with restaurants worldwide, and Thomas Keller, another famous chef and owner of restaurants, including the French Laundry in Yountville. But diversifying sales didn’t help the business enough, and Van Vleck realized his father was right: The ranch could not support more than one family. He created two other companies — one for commercial real estate and another for financial investments — that, along with the ranch, are subsidiaries of a holding company that he owns.

He took other steps to reduce the substantial debt he assumed when he bought out his siblings. Van Vleck says he has sold 90 percent of the 5,000-acre ranch as conservation easements. The easements allow developers to get credits to offset habitat loss that results from development of property elsewhere. Some of the land is part of the South Sacramento Habitat Conservation Plan, which aims to protect 317,000 acres. The easements allow Van Vleck to continue ranching and require that the property remain undeveloped forever.

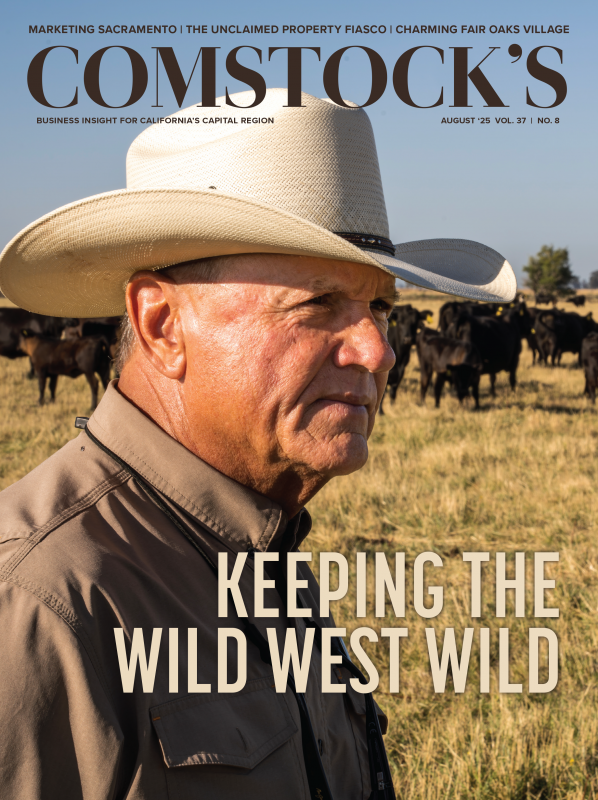

Stan Van Vleck owns a ranch that has been in his family since

1856. Originally located in what is now Apple Hill, the Van Vleck

Ranch now sits on 5,000 acres in Rancho Murieta.

A similar arrangement allowed for the preservation of the 279-acre Vista Ranch north of Lincoln. The Placer Land Trust, Placer County and the Placer County Conservation Authority formed a partnership to protect the land, while allowing ranching to continue. The land became part of the Placer County Conservation Program, which is similar to the South Sacramento Habitat Conservation Plan.

Van Vleck found another environmental option to help his ranching business — green waste. Municipalities deliver green waste — lawn trimmings and other items put in green recycling bins — to the ranch. The municipalities save landfill space while Van Vleck’s ranch benefits by having healthier grass, because the green waste becomes compost that is good for grass. And that means healthier cows and higher-quality beef. He says he is working with Verra, a nonprofit organization, to see if the practice can be used as a greenhouse gas credit sold to businesses. Green waste, once composted, stores carbon.

Van Vleck says he considers himself an environmentalist and thinks many other ranchers should too, considering their stewardship of the land. By diversifying his ranching business, Van Vleck says he has created options for his two children, should they decide to take it over. He says both of them have expressed interest.

Scott Stone: Three jobs, one love

To hear Scott Stone tell it, he works three jobs just to support his hobby of ranching. Stone works as an agricultural real estate broker, a real estate portfolio manager and a rancher. He is a partner of Yolo Land & Cattle Co., which has a 7,500-acre ranch outside Winters. The ranching company sells 100-percent grass-fed beef and beef jerky. Like Van Vleck and Lewis, Stone had to take on additional businesses to keep the ranch. Like Van Vleck, he has also adopted the same practice of accepting green waste from municipalities and hopes to sell carbon credits from compost.

The ranch is located in the rolling hills of the westernmost part of Yolo County. “Our ranch is a very special place,” he says, noting that developers once offered to pay him a substantial sum so they could turn it into a golf course.

Stone ensured the protection of the ranch in 2005 when he sold most of it as conservation easements to the California Rangeland Trust, a Sacramento-based nonprofit organization that has secured easements on 420,000 acres statewide. The easements allow ranchers to keep working but keep the land from being developed.

Stone says the easements helped him reduce the substantial debt he took on when he assumed some control of the ranching company once co-owned by his father. He would like his two sons to take over the ranching business eventually. But so far, they don’t seem interested, he says — not enough money in it.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

The Way We Work: Stan Van Vleck

A glimpse into the daily life of Stan Van Vleck, attorney and owner of Van Vleck Ranch

Stan Van Vleck is head of the 12,000 acre Van Vleck ranch, a family business that dates back to 1856.

In Land We Trust

The Yolo Land Trust has protected Yolo County farmers and farmland from encroaching development for more than 25 years

As modern-day farmers find it increasingly difficult to deny the financial gains of selling their land for development, the Yolo Land Trust gives them a viable business option to conserve their property.

Protecting Open Land

California Rangeland Trust project places fiscal value on the environmental benefits of ranches

Ranchers and those in the conservation industry know there’s an inherent value to working lands, such as cattle ranches. But how do they monetize that value?

A Tarnished Past

How stakeholders in the Sierra Nevada are confronting the lasting legacy of the gold rush

Over the past two decades, a coordinated effort focused on science and policy, education and awareness, and an entrepreneurial approach to workforce development has been underway to come to grips with the lasting legacy of the mining age.