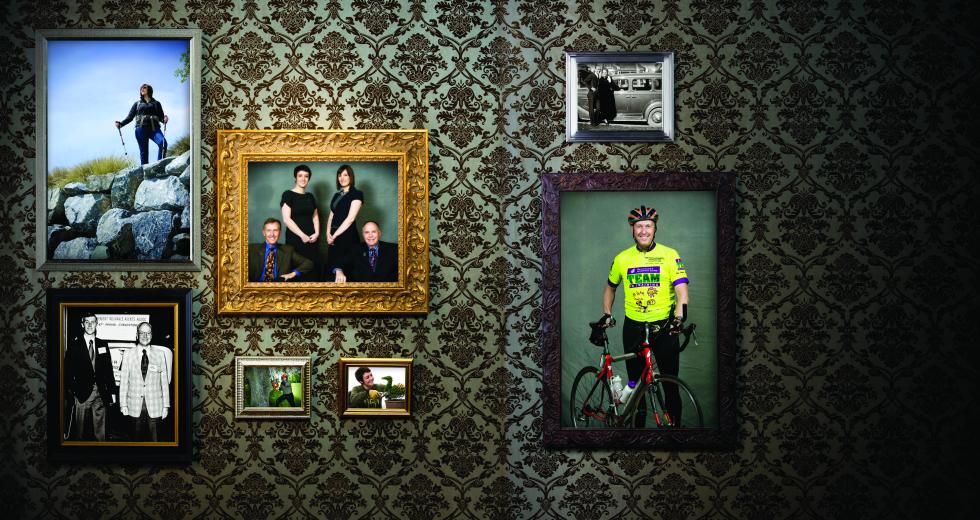

Steve Moore, of Rex Moore Electrical Contracting, spent a decade handing over the reins of the family business to a fourth generation.

Steve Bender plans to spend the next 10 or 12 years putting his family’s insurance brokerage, Warren G. Bender Co., in the hands of a third generation.

Both men know that fumbling the hand-off can kill the company. According to a study by Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co. in the late 1990s, only about one-third of family businesses survive to the second generation, and only about 4 percent make it to a fourth generation.

“Most people don’t understand that you need that time to groom the people who are stepping into that company,” Moore says. It’s not just about learning the mechanics of day-to-day operations. The new generation also has a corporate culture to maintain, one that includes nonfamily employees.

“The biggest mistake that a lot of people make is that they take their kids and put them at the top, and nobody else has any respect for them,” Moore says.

He didn’t get a free ride to his current job as chairman. His father started him out as a shop delivery boy, followed by a four-year apprenticeship program, before letting him work in the office writing job estimates.

A smooth transition takes baby steps.

“And not all those steps are the right steps,” Bender adds. “You make mistakes along the way.”

And that makes sense, he says, because it means blending the constants of the business itself with a changing mix of individuals.

Families have much better odds of success if they communicate more, says Peter Johnson, director of the Institute for Family Business at University of the Pacific in Stockton. Without good communication, it doesn’t matter who had the best intentions or who is best equipped to take over.

“The reason family businesses don’t make it to the next generation, many times, is not the success of the business. It is because of the family relationships,” Johnson says.

He tells of a client family that owns a big resort in New Mexico. The daughter had grown up in the family business but ended up working for the Ritz-Carlton chain instead. The father hadn’t wanted to pressure her, so he had never brought up the subject. She interpreted it as him not wanting her in the business. In other families, parents are so anxious to get the kids on board that the kids feel like they have no choice.

Bender says he somehow understood the need for communication.

“My father, who was Warren Bender, did not spend much time at all talking about family going into the business,” he says. “I think it was his belief that if it seemed right, then nature would take its course and things would work out. So he never really asked us to join.”

Bender did join, as did his brother, Jim. But once he was on board, Bender made a point of talking about the transition, a conversation that lasted 13 years until his father retired.

Eventually, Bender caught himself repeating the pattern when his middle daughter, Maggie, was in college.

“I always felt she had an aptitude for business, and I had this sense that she might be a good candidate,” he says. “But I never had that conversation until her junior year.”

He sat her down to discuss not only the benefits of the family’s insurance brokerage but the sacrifices it would involve.

“About a year and a half later, after she graduated, she said she’d like to give it a try,” he says. She has been with the company for five years now.

“It’s all about getting those multiple generations of shareholders to share values and a common vision.”

Kurt Glassman, CEO and president, Glassman Family Trust

Bender’s youngest daughter, Jillian, recently started to work for the brokerage, and his nephew, Chris, has been aboard for about 10 years. Some of their siblings have chosen other career paths.

Even if everyone is clear about who wants to join, the Institute for Family Business encourages families to send the kids off to work elsewhere for a few years.

“You want to let them see what is beyond the walls, so that they don’t feel trapped,” Johnson says. “It will create a great sense of what their self-value is. The other thing is, they hopefully will gain a great deal of knowledge that at some point they can bring back into the family business.”

Moore took a modified approach to that rule when his son, David, came to work for the family’s contracting company.

“I put him down in our Fresno office, and he learned from our business manager down there,” Moore says. “I wanted him to work for somebody else and get the respect of the people in another branch.”

A new generation is also working its way up the ladder at Pacific Coast Building Products, but none work directly under chief executive Dave Lucchetti.

“I think it gives them an opportunity to experience working for someone other than a relative,” he says. Lucchetti had a brief career as a high school teacher and football coach before marrying into the family of company founder Fred Anderson and joining the business.

Pacific Coast Building Products’ third generation is a larger group, ranging from their late teens to late 30s. The next transition won’t be simple.

“As the family grows, it becomes a more complicated process. I think people are recognizing that,” Lucchetti says. That’s one reason he and several other Sacramento-area families have joined the nonprofit Capital Region Family Business Center. In addition to the families helping one another through panel discussions, presentations and other gatherings, the center staff helps them sidestep “tripping points.”

A large family’s diverging interests is one such issue. Kurt Glassman, president of the center, says a family must be able to show unity to board members and nonfamily employees.

“It’s all about getting those multiple generations of shareholders to share values and a common vision,” he says. “If the family can set up this family council to speak in one voice, then the business has a chance. The family council represents the shareholder, in essence.”

Within the privacy of those group meetings, families need to hammer out the specifics of transitions, says Dianne Miller, president of executive search firm Wilcox, Miller and Nelson in Sacramento. For instance, what kind of dividends will the kids receive if one is working in the business and another isn’t? Can they be shareholders at all if they don’t participate?

“What you want is an upfront process that says, all things being equal, we are in this for the long term. We are going to make the decision that is best for the business,” Miller says.

Family-owned companies need to have formal buy-sell agreements, she says. They should spell out what happens if somebody dies or leaves the company. In their simplest form, they codify who has a controlling interest, and when.

For example, Moore set up a 10-year buyout, selling his interests to son David, who is now president; his son-in-law, Brock Littlejohn, who is the company’s chief financial officer; and Bill Hubbard, a nonfamily owner who serves as executive vice president.

“You really need to have these things in place before you get into succession,” Miller says. “It’s personal when you are in the succession; it’s process when you do it before.”

Drawing up such documents usually isn’t hard. Most corporations have them. But in family businesses, it can be tough getting all the players to sign off.

“The soft issues are really the hardest issues,” says Jim Sabraw, executive director of the Capital Region Family Business Center.

Few people could have a more attractive introduction to a family business than Jason Minow. At about 9 years old, he got to run the Icee machine at his parents’ business, The Sacramento Sweets Co. Inc.

He was a kid with the run of a candy store. But he didn’t care for the business end of things at first.

“The reason family businesses don’t make it to the next generation, many times, is not the success of the business. It is because of the family relationships.”

Peter Johnson, director, Institute for Family Business, University of the Pacific

“I was working on the weekends, and my friends were out of school and having fun. It took me a while,” he says. As he got into high school, he studied drafting and seemed headed in that direction. But in 1978, when his parents moved the store to Old Sacramento, Minow got involved in modifying the space.

“I was the one who went down to the building department at 17, 18 years old. That was an eye-opening experience,” he says. He stayed on, running the inventory. Gradually, he realized that being around his family every day — and getting to experiment with making candy — was what he wanted to do after all.

“What happened is that my dad finally let go of trying to control every little piece of it,” he says.

Today his mother, Carole, is retired. His father, Buz, comes by the candy store to take care of the company banking, but otherwise stays out of the picture. One sister, Cindy, comes in a few days a week to help. Jason doesn’t expect the store to pass to another generation.

“My son is a pretty good candy maker, but I don’t think he wants to do this. He has other ideas. He wants to go into sports medicine,” Minow says. “You really have to want to do this business. That gets back to me falling in love with it. It’s never going to be something that makes anyone a ton of money.”

With the family dynamic piled on top of ordinary business stress, it might seem logical for most families to sell after a while. But the same tenacity that causes family members to butt heads for years can also hold an operation together.

“One of the [peculiarities] of family-owned businesses is this compelling desire to create harmony and legacy and so on within the family,” Sabraw says.

Business success and family ties sometimes go hand in hand. And it isn’t always about the money.

“It’s a value system,” Moore says. “We had an opportunity to sell the business for a lot more money than I wound up selling to the three boys.” But Moore talked to other companies that had been bought out by the same suitor. The Rex Moore employees wouldn’t have been as well off, and the new generation of the family wouldn’t be owners.

Johnson at the Institute for Family Business quoted a client, a landowner whose family has been farming in the San Joaquin Valley for more than a century: “I could sell the land and put the money in the bank and make money off the interest and not have to work six days a week. But I’m not going to let this 100-year-old family business die on my watch.”

Johnson finds another quote cropping up often when he brings a family in for a program at UOP where they hear the squabbles other family-owned companies are going through: “We didn’t realize other family businesses are just as screwed up as we are.”

That ability to tap into one another’s experience within a formal framework is relatively new. The Capital Region Family Business Center, for example, has only been around for three years.

“Every time I or the kids walk away from one of these family business center events, we usually have a refinement in our business discussions,” Bender says. “It’s not just going to the programs and learning. It’s creating relationships and being able to pick up the phone and talk to someone in farming or manufacturing and say, ‘How are you handling this?’ That is something we never had before.”

Recommended For You

It Runs in the Family

How nepotism turns good business into bad blood

Left unchecked, underachievers can drag down an entire team’s performance, and that goes double when the problem staffer is family.

Family Planning

Strategies for a prosperous succession

When Albert and Frances Lundberg fled the Dust Bowl-ravaged cornfields of Nebraska in 1937 to settle in the greener pastures of the northern Sacramento Valley, they did so with hope for the future.