Shan Dan Horan is getting fed up with a glitch.

The Gold Rush-era building in Old Sacramento where Artery Recordings, a record label, is based has a weak internet connection. Horan has gathered his team in the conference room for another installment of a monthly web series for “A&R” — also known as artists and repertoire, or the scouting of new artists — with thousands of viewers tuning in. “When you stream live on Facebook, you have to use a mobile phone,” says Horan, Artery’s president. “This doesn’t make sense to me, because you’re reliant on your connection. So are we live or not?”

Horan has been rushing around on this August afternoon trying to make up for the 10 days he spent out of the office. This isn’t a good time for glitches. He returned from London the day before, where he met with his company’s European distributor and filmed three music videos for the blackened-deathcore band She Must Burn.

The company’s head of new media, Chris Gacayan, resolves the glitch and informs the group they can now officially start. Horan clicks play on a music video with 12,300 views for a song called “We All Die.”

Bands or their fans submit links to videos via email or as comments on Artery’s Facebook page. The Artery team watches the videos for about a minute and a half, along with their Facebook fans, giving both the record label and music lovers a chance to discover unsigned bands worthy of attention.

“I thought the vocals were on point,” Horan says. “This guy can actually sing.”

He solicits feedback from his peers.

“One thing I do love about this video, it’s a really good example of what you can get done on your own for relatively cheap … They don’t look like they’re an unsigned band from the video,” says Will Stevenson, Artery’s vice president.

Javin Romero, left, and Shan Dan Horan film inside the Gold

Standard Sounds recording studio in Sacramento. (photo

illustration by Jason Sinn)

“That’s the most important thing,” Horan says. “You want to be a big band, you got to look like one.”

Artery Recordings is a modern-day label and sits under the umbrella of the Artery Foundation, a full-service artist management company based in Sacramento. Horan says he pioneered this type of A&R web series, which uses crowdsourcing to identify artists with their own buzz and the potential to make a strong impact on listeners. The series has received a total of 60,000 video submissions and 400,000 views since launching nearly a year ago, and has played a part in Horan signing two new bands.

The label is also piloting a television show and is always looking for new ways to innovate — a must for anyone navigating the music industry’s ever-changing landscape. Their strategy seems to be working. The company, Horan says, is growing faster than its competition around the country. Artery has signed roughly 50 bands worldwide and surpassed 600,000 record sales in six years of existence. While three major labels still dominate the industry, smaller independent labels have begun encroaching on this space. They took 35 percent of the U.S. market last year.

The next video for a French metal band has the group cracking up. A playful bassist, clad head-to-toe in pink, shakes his hips and eyes the camera seductively. But the incongruity between the music’s tone and its delivery works. “I thought that was freaking rad,” Horan says. “You don’t see stuff like that very often.” Thumbs up and happy faces dance across Artery’s Facebook page as thousands of viewers give their feedback in real-time.

Filling a Niche

A couple months later on an October afternoon, the four members of the indie pop band The Color Wild, ages 17 to 22, arrive at Gold Standard Sounds — the Artery Foundation’s recording studio — in a nondescript building on an unremarkable street in Sacramento. (The interior is a different story.) They shake hands and make introductions, then stand around with their arms crossed. The musicians found out only a few weeks earlier their band would be chronicled in a pilot television show Artery Recordings is developing with an executive producer in L.A. The premise is similar to Chef Gordon Ramsay’s “Kitchen Nightmares,” but with a band to be fixed.

The cameraman, Javin Romero, adjusts his equipment. He’s come up from L.A. to help Horan — his friend for 16 years, since the two got into trouble together as teenagers in Flagstaff, Ariz., he says. “How does that audio sound? Do you need to boost it, or is it peaking?” Horan asks. He leads the band outside, taking off his black blazer and tossing it over his shoulder, where it will sit undisturbed for the next hour.

The Color Wild’s keyboardist Jesse Crosson steps forward to be interviewed. The bandmates are three brothers and one buddy who grew up in Vacaville and now live in Sacramento. “I know for us being brothers and being related has helped the band’s chemistry,” Jesse says.

“Don’t direct your attention toward me,” Horan says. That’s lesson No. 1 for the young band. Lesson No. 2: When interviewed, re-state the question as part of the answer for a better soundbite.

A helicopter flies above, interrupting the recording, and Horan looks overhead: “I swear to god,” he mutters. The distraction passes and the recording resumes.

Shan Dan Horan and Javin Romero film Jesse Crosson, keyboardist

in The Color Wild, for a television pilot Artery hopes to sell.

People get into music for deep reasons, Horan says, asking Jesse for his motivations. “I think everybody looks for ways to express themselves and get their message out there,” Jesse says. As a quiet person, it’s his way of speaking.

“That was a pretty sound answer.” Horan says. “What do you think we have in store for you?”

“I honestly have no idea,” Jesse says.

Horan, on the other hand, has a plan to make this band “larger than life.”

At 32, Horan looks the part of a metal-music guy. He’s usually wearing some variation of black pants, black top and black shoes, accessorized with 1-inch gauges in his ears and tattoos that cover his arms and throat. His favorite tattoo is a heart with the word honor on his left hand. “Just reminds me every day to try and do the right thing.” His look has gotten him stares during trips to Japan, England, Russia and Australia. “Tattoos tend to reflect criminals or social misfits,” he says. “People with that stigma tend to scowl at me or even — this has happened — get up from the subway seat next to me and move. They have no idea what I’ve accomplished in my life or who I am. To them I am not a member of society. The other reaction is when you bump into someone wearing a metal band shirt with tattoos that gets it.”

A few years ago, Horan was working for a major heavy-metal record label in Chicago. But when the Artery Foundation came calling in 2014, he left the Windy City for a position as head of the New Media Division for the company. Artery founder Eric Rushing says Horan was responsible for growing revenue over 200 percent through new media revenue in his first year alone — he developed a digital marketing strategy to increase sales from digital downloads, streaming and a monetized YouTube channel. Within about a year, Horan had been promoted to president of Artery Recordings.

Rushing launched The Artery Foundation in 2004. The management company handles every aspect of a band’s activities — touring, recording, merchandising, media relations, marketing and social media. At some point or other, Rushing has owned stakes in Sacramento music venues Ace of Spades and The Boardwalk, and restaurants Goldfield Trading Post, Tank House and Low Brau. He also owns Gold Standard Sounds, a talent agency called Artery Global and a public relations firm called High Road Publicity.

But Rushing started to notice that he might be missing out on a major opportunity. “[The Artery Foundation was] finding most of the bands for our colleagues’ labels but not benefiting from the signings as the bands decided to leave the management company and bounce around to other companies,” Rushing says. “This is pretty much the norm as bands decide to move around after three to five years at a company. Having the record label is much more beneficial as you cannot leave a record company until your deal is up.” He launched the Artery record label in 2010, partnering with Sony Music as the distributor.

“A local artist would be foolish not to have their music on as many platforms and streaming services as possible, because the name of the game is get more listeners.” Keith Hatschek, director, Music Management and Music Industry Studies, University of the Pacific

Selling over 600,000 records as a start-up label “is very tough to do in the decline of record sales,” Rushing says of Artery Recordings’ early success. “I cannot name another label in the industry that started up as an independent in the last six years and has sold that many records.” Smaller record labels like Artery may be the future of music. Large bands have started launching their own labels and releasing music with major distributors. “They can carve out a bigger piece of royalties for themselves by doing this,” Rushing says.

Is Streaming the Future?

To survive, Artery — like all other labels — will need to keep innovating. Although their record sales may be impressive, it’s not the best indicator for how a label will fare into the future. Horan knows this. So Artery has diversified its revenue streams and embraces streaming platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music, which allow users to cherry pick songs and create their own version of albums as playlists. These platforms are either free or fee-based for subscriptions; the sites also make money through advertising.

A download on iTunes costs on average between $.99 and $1.29. Of that amount, Apple keeps a percentage (about $.30 for a $.99 download), explains Keith Hatschek, director of the Music Management and Music Industry Studies at the University of the Pacific in Stockton. The remainder goes to the rights holder, which is usually the record label. The label has agreed-upon terms with the artist and songwriter (who might be someone else) for how much money they get — minus the sum due to the label by the artist for making the record and other expenses.

An artist gets only a fraction of a cent per play on streaming services like Spotify. But that might not be as bad as it sounds. “Streaming is much less per stream, but potentially a fan can stream a favorite song many, many times, versus a larger one-time payout to buy the song as a download,” Hatschek says.

Horan declined to share how much Artery’s bands are compensated for streaming, digital and physical, due to varying rates depending on the artist, though he claims the label treats its musicians better than most other labels.

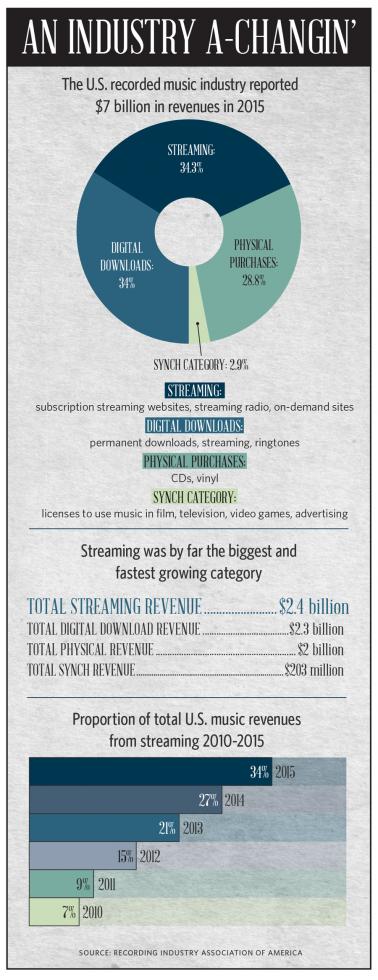

According to the Recording Industry Association of America, the U.S. recorded music industry continued to transition to more digital and more diverse revenue streams in 2015, and last year marked a milestone year for streaming music. For the first time, streaming represented the largest component of industry revenues, comprising over 34 percent of the market — exceeding $2 billion. The streaming category incorporates subscription sites like Spotify, streaming radio services such as Pandora and on-demand services like YouTube. Streaming just barely surpassed digital downloads by less than a percentage point, also at 34 percent. The physical category (CDs, vinyl) accounted for 29 percent and the synch category (licenses to use music in film, television, video games, advertising) took 3 percent. All told, the industry reported $7 billion in revenues.

Nielsen Music’s annual report for 2015 supports RIAA’s findings. According to Nielsen, streaming nearly doubled from 164.5 billion songs streamed in 2014 to 317.2 billion last year. That’s a 93 percent increase. And music consumption overall grew by 15 percent over the year prior.

Artists haven’t always responded agreeably to streaming because of the low royalty rate. Radiohead initially criticized Spotify for its unfriendly-to-artists economics, but has since made amends. Taylor Swift famously removed her songs from the service in 2014 and wrote an op-ed defending her decision in the Wall Street Journal. In 2015, Adele refused to release her “25” album on streaming services until it had been out for seven months; the album set first-week record sales. But Beyonce and Jay-Z saw an opportunity and started their own streaming service, Tidal, in March 2015, with several other popular musicians also owning shares in the business.

Two of the world’s three biggest record companies — Universal and Sony — originally pushed back against streaming; Warner, on the other hand, eagerly partnered with streaming services. Many labels are starting to come around and see the value. Some of the major ones now have an ownership stake in Spotify.

Some industry experts have suggested artists like Adele were inflating sales and ignoring the inevitable shift away from music consumption as something you can hold in your hand. “Adele and Taylor Swift have the luxury to pick and choose how, when and under what conditions to make their music available,” Hatschek says. It made sense from a business perspective, but they risked losing a younger audience that expects a different kind of access. “A local artist would be foolish not to have their music on as many platforms and streaming services as possible, because the name of the game is get more listeners,” he says.

The game has changed a lot since Hatschek was a young musician a couple decades ago — when the goal was to save enough money to pay for a few hours of studio time to record a couple songs. Today’s technology enables any band to produce their own music at a fraction of the cost. With fewer gatekeepers, this democratization has brought audiences Kendrick Lamar; Tyler, the Creator; and Ed Sheeran — voices we might not have heard otherwise, Hatschek says. But, like in other industries, some say the digital shift has also brought a glut of less-than-stellar product.

Ultimately, the fundamentals of being a successful commercial artist remain the same: A musician needs a song with a catchy melody to capture attention; the knowledge to license and protect the music; and the know-how to engage followers. “Building an audience is in some ways greatly more complicated and daunting than making the music,” Hatschek says.

Revenue comes in different forms nowadays, less from physical products sold to consumers and increasingly from streaming, licensing, endorsements, merchandise and tours. Producers and songwriters still earn the highest royalty rate from selling albums. But when it comes to music consumption, the younger generation simply isn’t into ownership as much as listeners once were, Hatschek says. They don’t care about stockpiling a personal album or CD collection. “It’s a different mix of revenue now, but the revenue is still there,” he says. Commercial superstars like Taylor Swift, Drake, Rihanna and Adele prove that point.

Artery has seen firsthand how as live-streaming revenue goes up, digital sales goes down. Their biggest revenue remains digital downloads “for sure,” Horan says, but it’s hard to know how long that will last. The amount of money an artist or label can make per interaction on streaming versus digital download is tremendously less.

“It’s a little scary because if you can’t make as much money on a release, you can’t spend as much money on a release,” Horan says. On the plus side, potentially many more people are exposed to a band’s music. What an exciting prospect, he says, because a band can blow up overnight.

Piloting a New Idea

The Artery team agrees that The Color Wild is talented. They might blow up overnight. And they’re easy to work with, which was a big factor in their selection as the band to feature in the television pilot. The L.A. producer has been pitching the show to networks, Horan says.

“We were juiced,” says lead singer Kyle Crosson, of finding out they’d been chosen among other local bands represented by Artery.

In addition to Kyle and Jesse, the band also includes drummer Jaden Crosson and lead guitarist Josh Hansen.

“Juiced is the right word,” Jesse says.

The Color Wild has played The Boardwalk and City of Trees in Sacramento and Whiskey a Go Go in West Hollywood, but getting to appear on a TV show would make these guys more than just a local band, exposing their indie pop songs to a new and wider audience. “At the end of the day, you make music because you want other people to hear it,” Hansen says.

They could use some refining, though, and over the course of the week they will record their songs with a professional producer, get makeovers, new promo photos, new album art and new marketing materials — all while being filmed. Their televised story will end with a big reveal.

“And hopefully,” Horan says, “a little tear jerker moment: ‘We made it.’

Comments

Very happy to see that you have chosen The Color Wild for this project!