Imagine a father who is the CEO of a company, and he employs his son. But the son is lazy. He misses deadlines, he loses clients, he flubs task after task. Finally the father has had enough. One night at home he turns to his son and says, “Well, son, I’ve got to tell you. You’re fired.” Brief pause. “Now let me put on my family hat. I heard you’ve had a really bad day. Let’s talk about it.”

Ken Monroe, chairman of Family Business Association of California, shares this anecdote with a chuckle. He says it’s an example often shared by family business consultants, as it illustrates the complex dynamics that can cause added stress, anxiety and conflict at both home and work. Families can be stressful. So can businesses. And working in a family business? The stress compounds and multiplies.

In the larger cultural context, this is perhaps more relevant than ever. Amanda Blackwood, president and CEO of the Sacramento Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, says we are in a “perfect storm” of both experiencing and acknowledging mental health issues, as stressor after stressor continues to pile on — the original burdens of the pandemic, the seesaw of thinking COVID-19 is over and then reeling from the delta variant, the awful ambiguity of schooling and child care, and on and on. Then gymnast Simone Biles gave it global awareness.

“It’s a moment in time when someone so prolific normalizes something, and makes it a little bit easier for ‘normal people’ to be able to say, ‘You know what, I’m not OK either.’” Blackwood notes that in one study (a 2018 study from the health insurer Bupa Global), more than six out of 10 senior business leaders suffered from mental health conditions, and she suspects it’s almost certainly higher for family businesses.

The root cause? The experts all agree on essentially one thing: It’s complicated. “All of the relationships are just so much more complex,” says Blackwood, and it’s “layered with familial expectations and history.”

The Complications

The tension often starts with generational fissures, which can take many forms. “When you’re the generation coming up, you’re always compared to the previous generation,” says Monroe. “That can be tough, particularly if the founder has a very strong personality.” Most children feel a certain pressure to make mom and dad proud, but that can be overwhelming when the parent happens to be a legend. (Consider the classic family business story, “The Godfather,” where Michael Corleone could have used a therapist.)

Then there’s the opposite side. Stella Premo, executive director at the Capital Region Family Business Center in Roseville, says the older generation might bristle at the younger generation’s push to take a riskier approach. “The founding generation is saying, ‘Hey, kid, I built this business, and it’s also my retirement plan. You can’t play with my future,’” says Premo.

“When you’re the generation coming up, you’re always compared to the previous generation. That can be tough, particularly if the founder has a very strong personality.”

Ken Monroe, Chairman, Family Business Association of California

Then there are the blurry lines between family and work, parent and boss, sibling and vice president, wife and CEO. Anxiety and depression often stem from “the lack of boundaries between work and home,” says Sean Davis, a family therapist and founder of The Davis Group, based in Roseville. Davis says conflict sparks when one spouse says, for example, “You can’t boss me around,” and the other responds, “Well, yes I can, I’m the boss,” and then “No you’re not, you’re my wife.”

Money issues add more complications. Lois Lang, a family business consultant with a background in psychology who specializes in succession planning with Evolve Partner Group in Stockton, says some next-generation workers can be on “the family plan,” receiving cushy salaries that are not deserved. This can cause resentment and guilt. Or it can flip the other way: The son or daughter works his or her tail off for less than market value, because mom and dad are dangling the carrot of future ownership. Either scenario is “not really fair,” says Lang, as “it should be totally separate.”

Another source of “not really fair” is succession planning. There’s a reason one of the most drama-packed shows on television is called, well, “Succession.” Lang says the show rings truer than you might expect. Succession planning is “a stressor on all generations,” says Monroe, thanks to the brutal questions it raises: Who will inherit the brass ring? When is the matriarch forced out? And then the lurking questions beneath the questions: Which sibling does mom love best? Am I good enough? Do I deserve this?

To complicate things even further, the family members who are not in the family business can be a frequent source of anxiety. Maybe it’s a sibling, or a spouse or the other parent. “Maybe the husband doesn’t work there, but the son and daughter do,” says Lang. “At the kitchen table he will feel excluded, and he’s sick of hearing about it.”

This is not to say all family businesses, or even most, are rife with conflict and mental health issues. And clearly there are benefits, such as the pleasure of working with the people you love. “I am not aware that family businesses cause any more mental strain than other kinds of businesses,” says Robert Rivinius, executive director of the Family Business Association of California. But he also adds this: “Except for the possible stress of dealing with some family members.” And there’s the rub. So here are 10 strategies the experts recommend:

1. Set Crisp Expectations

Since much of the tension stems from ambiguity, Monroe says that a leader should set crystal clear expectations. True in any business, but crucial in a family business. “The kid might not work for the parent (CEO), but the parent should be clear to the supervisor and say, ‘I want this kid to be treated like every other employee,’” says Monroe. Stick to objective criteria for how to evaluate performance, says Premo. “People want to win,” she says. “They want to be able to look at their annual review, or mid-year review, and say ‘I am winning at my job, and I’ve met my expectations.’”

2. Knock Out the Succession Plan Before It’s Urgent

Lang recommends that a CEO should start succession planning at least 10 years before she plans to retire. This lets it happen in a time of relative calm, as opposed to the urgent panic that can lead to stress or anxiety. As Lang is often hired by family businesses that are embroiled in messy, complicated succession nightmares — families that waited too long to create a plan — she now jokes, “I’d make a whole lot less money if they called me in the beginning and said, ‘10 years from now I want to retire.’”

3. Set Boundaries

“They have to have really clear boundaries between home and work,” says Davis. No talking about the third quarter financials at the family barbecue. This goes deeper than just when you talk about work, says Premo — it requires viewing your family members in a different light. “When you’re the CEO,” she says, it means looking at your daughter “not as your child, but as the senior vice president.” Or as Kurt Glassman, a Sacramento-based family business consultant puts it, “You have to separate the family from the business.” And because that is not always possible, sometimes you need to do the following …

4. Bring in a Third Party

This could take many forms: a family advisory board, a family business consultant, or just “someone who specializes in the family business background,” says Monroe, adding that ideally a third party should have some kind of psychology or soft skills experience, and can be an “objective outlet for all parties to dump their buckets, both positive and negative.”

5. Listen

Davis calls active listening “a necessary ingredient of an effective family business,” explaining that the real trick is to listen on “multiple layers.” Often with family businesses, says Davis, the literal comment could be about work, but the subtext might concern the family relationships. He gives a theoretical example: Maybe a wife wants to buy a new printer and asks her husband, the CEO, who snaps, “I don’t want to buy another printer right now!” Perhaps there’s something deeper at play. Davis says if we truly listen, we might be sensitive to that “he’s really stressed about money because grandma just got diagnosed with cancer, and it’s going to fall to us to take care of her.”

6. Consider Exiting

There is no law that says you must stay in the family business until you retire or die. We forget we have options. Lang says a clean exit is something that family business members rarely contemplate, but perhaps should. “People don’t want to even think about that,” she says. To save the family, you might need to quit the business.

7. Check In With Yourself

How to tell if you’re feeling garden-level anxiety or something more serious that’s a mental health issue? Lang says the most common signs are panic attacks, acute anxiety, insomnia and a drop in performance. Blackwood says maybe you’re unable to focus on a task (like doing the accounting books) that you can normally do in your sleep, or perhaps you can’t remember the directions to a place you’ve driven to a million times. “You may really be having an anxiety issue or depression issue that, if untreated, is bound to get worse,” says Blackwood. “And in a family environment, compound it 10-times.”

8. Normalize Empathy

This starts with leadership. Make empathy a common practice. Blackwood recommends before you plunge into a staff meeting, for example, start by asking, How are we feeling? What’s on your plate? After her team had missed a few deadlines, she tried this in her own staff meeting. She was surprised to learn that one colleague had an elderly mother who had just come down with COVID-19 and was worried her mother would die. “Had I not taken a moment to have that conversation, I would have approached it in absolutely the wrong way,” says Blackwood. “They wouldn’t have heard me, it would have been insensitive, and I wouldn’t have gotten the outcome I needed.” Once they connected as humans, then they could “talk about this business problem that we all wanted to solve.”

9. Communicate, Communicate, Communicate

Obvious? Perhaps. But somehow it’s often overlooked. Lang recommends regular family meetings, even if it’s just once every other month. Glassman says steady communication and check-ins are critical for spotting incapacity issues, as “incapacity issues don’t happen overnight. They’re ongoing. You’ll be able to see signs, but if you’re not engaged, you won’t see the warning signs.” He says this logic holds true not just for elders, but for detecting mental health issues with anyone in the business.

10. Remember the Upside

And finally, on a more hopeful note, Davis says that “When a family business works it’s really, really cool. It can set up that lineage, so to speak, for generations. But it does require a high degree of communication. And a lot of humility.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Passing the Torch

Running a family business for multiple generations can be tricky, but several local companies have found a way.

Can Artificial Intelligence Improve Mental Health?

After the disruption of 2020, the push for more collaborative affiliations has become even more urgent. At the core of this evolving model is technology.

Family-Owned Businesses Are an Important Part of Our Community

Comstock’s president and publisher considers the many shapes and sizes of family businesses in the Capital Region.

Cruising Through Change

Family business close-up

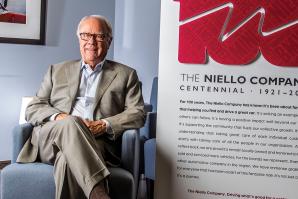

Started by Louis Niello in San Francisco as a shop specializing

in repairs and maintenance of Packard automobiles in 1921, The

Niello Company is celebrating four generations of family

ownership.