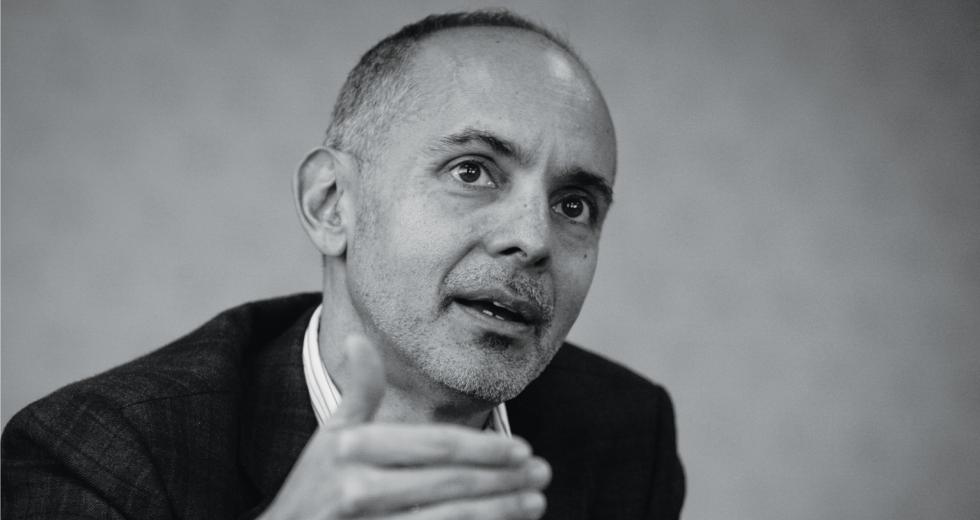

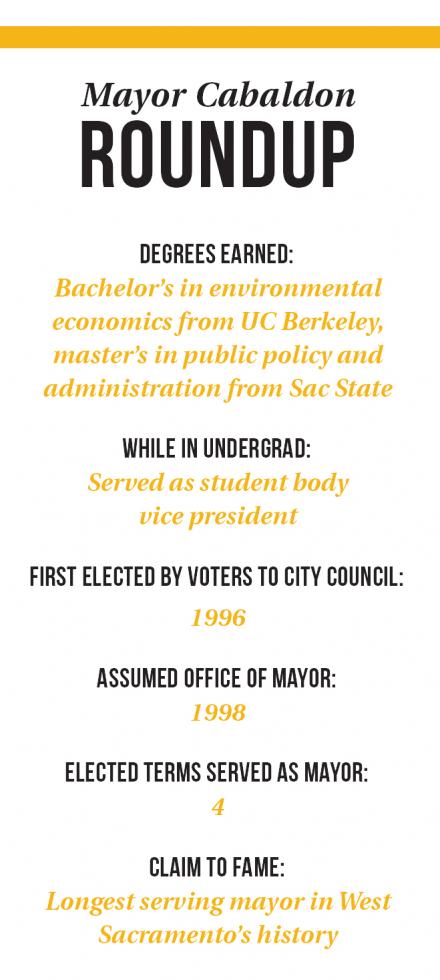

As West Sacramento’s mayor since 1998, Christopher Cabaldon has been an integral part of the city’s metamorphosis from a gritty industrial outpost to one of the region’s most up-and-coming locales. We recently sat down with him to talk about riverfront development, craft breweries and the impending “green rush” of legal marijuana.

West Sacramento is one of several cities in the Cities of Learning program. Tell me what that means for the city.

West Sacramento is widely seen as one of the more successful and dynamic cities in the region, but we still have high unemployment rates because of a gap between the needs of higher-skilled jobs coming here and the kind of skills that exist in our population. So it’s a real challenge for us. What we’ve embarked on with Cities of Learning is an entirely different approach. It’s not about school reform or even about the schools directly, but taking account of the fact that 80 percent of a young person’s waking hours are outside of school.

There is an abundance of learning opportunities in all that time: at the library, in a summer reading challenge, doing an internship, or just watching TV or playing ball. But it’s largely not connected in any sort of way or linked to the main education system. [Say you] do some volunteer work and when it’s done, it’s over. It doesn’t lead to anything necessarily … But the fact that you started to get passion and experience and skills doing that doesn’t stick with you in any formal way. And that is a problem.

The Cities of Learning initiative is about this thing called digital badges and playlists — creating a system that exists in the digital space that marks these kinds of activities and competencies and achievements, and allows them to link together and create playlists or paths of how those things can build on one another. And then, importantly, as you get older and ready to go on to college or the military or a career, that body of work and evidence of your passion and demonstration of your achievements — your career readiness, the fact that you show up on time, all that stuff — it exists in a place that you have the ability to direct a college or employer to see. So it’s an ambitious initiative, but it’s also one of the most significant and promising youth-development and workforce-development initiatives in the country.

West Sacramento has become a significant part of the so-called ‘Beer-muda Triangle.’ What does this influx of microbreweries mean to the city?

It’s been fantastic for the city, in that it has created more places for people to hang out together across generations, whether people have lived here for 50 years or five minutes. Places where people love to take their friends or family visiting from out of town, the kind of places that make a community. So they’ve been a win on every single dimension. They’ve almost all been started by West Sac residents, too.

They’re highly valued in the city, but the interesting thing is they were not part of our plan. If you look at our economic development strategy documents from six years ago, there were no craft breweries. There were no urban farms … But it is good that things here mainly don’t happen because of the city. We don’t drive amazing things. We make sure the toilets flush and the fires get put out. Amazing things are done by crazy people who put their life savings on the line and try something different and break all the rules. Our job is to figure out how to be the most effective platform for those creative, risk-taking people to do amazing things.

Related: West Sac Embraces Technology, Innovating Thinking

Development on your side of the riverfront is doing well, which seems to have spurred renewed efforts for similar development on Sacramento’s side. Do you see these as collaborative or competitive ventures?

It’s both. It started off as pure collaboration. We had a joint waterfront master plan that we developed when Heather Fargo was mayor in Sacramento, and it gave us the right template to look at the possibilities and to raise the right questions. But that sort of collaborative approach turned out to be a little slow because trying to do everything together meant everything took twice as long. So collaboration alone was not a good strategy.

Cutthroat competition is also a bad strategy, and pointless. So our approach now is that we are competing for very specific things … for who can do what and faster, but not in a cutthroat way. If we hadn’t done Raley Field, then Embassy Suites wouldn’t have made sense. If there was no Embassy Suites, the CalSTRs building might not have made sense. It’s a volleying back and forth in terms of what’s enabling the progress to happen.

“Amazing things are done by crazy people who put their life savings on the line and try something different and break all the rules. Our job is to figure out how to be the most effective platform for those creative, risk-taking people to do amazing things.”

Mayor Christopher Cabaldon, City of West Sacramento

Developing the railyards and re-centering Sacramento’s downtown, with the arena towards the west and moving the center of gravity of the urban core towards the river, will be the two most important things they do on the riverfront … So the timing has been slow but I think it’s definitely now ripe for both sides of the river.

California has finally adopted rules for regulating medical marijuana, with the details left to the cities to figure out. There’s also a lot of speculation that voters this fall might legalize recreational use. Is West Sacramento prepared?

I don’t think anybody is fully prepared, but we are trying in a couple of dimensions. One, if you split the consumption side from the rest of everything pre-consumption — growing, packaging, sorting, distribution, logistics, all that — they have different implications and issues. We were one of the first ones to try to authorize dispensaries, but we ended up as one of the first to ban them because we couldn’t reach an agreement with the dispensary advocates around a legal framework so that they wouldn’t sue. So the only legally defensible position was to have an outright ban. It’s definitely not where I wanted to be or end up.

When it comes to consumption on the non-medical side, it’s not clear to me what that market is ultimately going to look like. Probably not exactly what the advocates think it’s going to be. It never is. Once there’s that level of money on the table, if you’re not accounting for how Costco is going to approach this, or if you think your dispensary is going to double in size without accounting for the incentives for the rest of the mass markets to start entering, you’re making a mistake. So we’re trying to mostly watch that part of the market. On the industrial side, the pre-consumption side, we’ve had a lot of interest from folks wanting permits and that sort of thing already.

Some of my colleagues on the city council probably won’t be voting for any of these initiatives. They have concerns, even on the industrial side. My own point of view is there’s a lot of stuff that we’re currently warehousing and trucking and processing in the city that you would not want in a shop next to a daycare center, but that’s what an industrial city does. We always have been an industrial city … We have the right protocols for safety and security already in place for all of the biotech products. So we are already putting in place the protocols and procedures for the logistics, distribution, manufacturing side of the [recreational marijuana] business to be located here, on the expectation that those initiatives will happen, in addition to some of the changes that have happened on the medical side as a result of legislation.