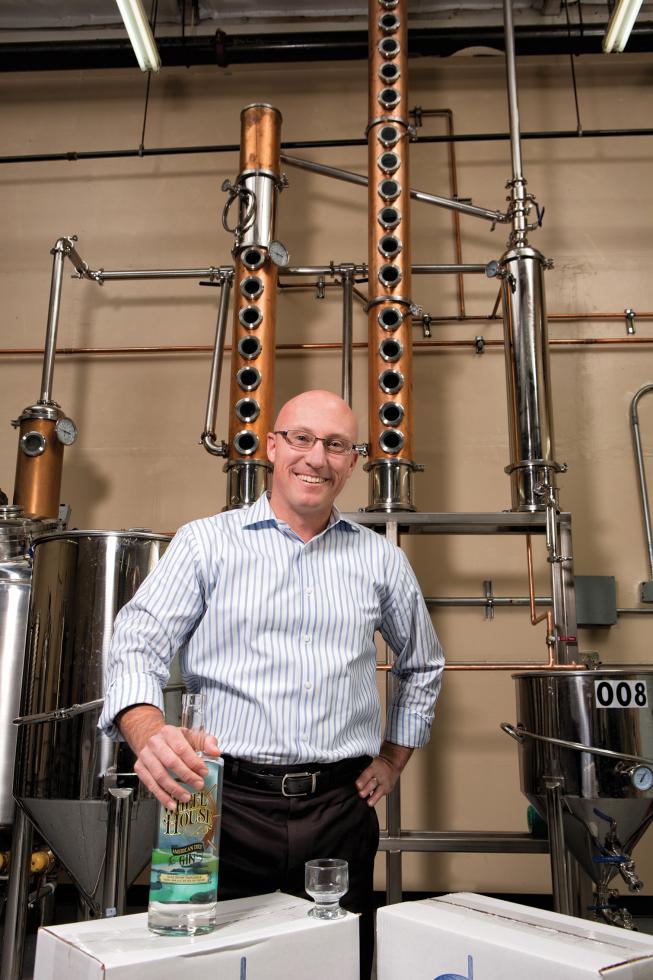

In a makeshift distillery tucked into a Rancho Cordova business park, Greg Baughman mashes and ferments batches of his Wheel House American Dry Gin using a still he designed and built himself, a gleaming vision of stainless steel and copper.

But actually sell you a bottle? For that he needs to hire a middleman due to regulatory hurdles dating back to Prohibition. Navigating liquor regulations is just one of the challenges facing California’s craft distillers. But pioneers like Baughman and other microdistillers in the region are betting that smart marketing — and consumers’ thirst for local, well-made products — will give them a shot at sustainable revenue.

The microdistilling movement, which is experiencing a boom nationwide, in California dates back to 1982 when St. George Spirit opened in the Bay Area. There are now more than two dozen distilleries in the state, including three in the Capital Region: Baughman’s Gold River Distillery, Amador Distillery and Dry Diggings in El Dorado Hills. A fourth, Hawj Bros. in Yuba City, which primarily made Asian spirits distilled from rice, opened in 2008 but has since closed.

California distillers got a boost this year with a new law permitting them to offer paid tastings (as opposed to the old system that allowed distillers to give only free samples), something their comrades in the wine and beer business have been doing for decades.

But California still does not allow distillers to sell bottled alcohol directly to consumers, which means that if consumers like a product, they have to purchase it from a third-party retailer.

That’s one reason Baughman doesn’t offer tours or tastings at his distillery. Instead, he’s come up with other ways of catching the public’s attention, including keeping an active presence on social media, visiting stores and restaurants to personally promote Wheel House and playing up his news value as the first (legal) distillery to open in Sacramento County since Prohibition.

Greg Baughman produces Wheel House American Dry Gin, a craft

spirit, at his microdistillery in Rancho Cordova.

The California Artisanal Distillers Guild is going to introduce a bill next year that would allow direct sales, according to Cris Steller, the guild’s executive director. A previous legislative effort by Bay Area Democrat Nancy Skinner proved a rallying point for distillers. The guild has grown from about 14 members two years ago to 42 today, says Steller, a partner in Dry Diggings Distillery.

Like the other distillers, Steller says he’s not interested in cutting out distributors; anyone with any kind of volume needs the connections and help of professionals. “If we sell a bottle to someone from Wisconsin, they’re not going to fly out here to buy another bottle because I’m that wonderful of a guy,” he says. “What we want is the ability to create brand recognition.”

Dry Diggings, set to open a tasting room in El Dorado Hills by year’s end, is the culmination of a 10-year dream. Spirits include vodka, brandies and whiskey and, in an interesting twist, the distillery is partnering with local wineries to make spirits from surplus juice. Ultimately, Steller would like to see such partnerships expand so that El Dorado Hills can develop a combined wine, beer and liquor tasting trail. The El Dorado Winery Association already includes 42 wineries, and the foothills off Highway 50 also house a half dozen microbreweries.

California’s new law, which allows distillers to pour up to six samples at no more than a quarter-ounce per pour, had an immediate effect for Adam Stratton, owner of Amador Distillery in Jackson, which offers tours and tastings. (Dry Diggings and Gold River don’t do tours or tastings, although they do pour at special events.)

Stratton’s not making a killing on his tastings, which cost $10 and include five quarter-ounce pours. He gives paying customers shirts and/or tokens, redeemable at area restaurants. What changed is that his customers got more serious. “Once people have a financial investment in a pour,” he says, “they pay more attention.”

Amador Distillery, which opened in spring 2013, now hosts two or three tours a week with sizes ranging from two to 10 people. His spirits, which include two bourbons and two ryes, are available in 150 bars, restaurants and stores.

“If we sell a bottle to someone from Wisconsin, they’re not going to fly out here to buy another bottle because I’m that wonderful of a guy,” he says. “What we want is the ability to create brand recognition.”

Chris Steller, executive director, California Artisanal Distillers Guild

That’s still not enough to allow him to give up his day job selling auto body parts, but it’s promising. Stratton says he would love to be able to sell directly to consumers. Not because he wants to fire his distributor; he doesn’t. But it would be nice to be able to make a small batch of brandy and sell it in the tasting room.

Recently, he made 18 bottles of slivovitz, a distilled liquor made from plums, for a special event. In order to sell it to the event organizers, he had to first drive it down to a distributor in Stockton and then have it sent back to Jackson at a 15 percent markup. Baughman currently spends about $11 making a bottle of gin, sells it to a distributor for around $15 and then sees it retail for about $30.

The impact of a friendlier legal climate could make a big difference. Portland, Ore., has a thriving distilling scene that includes Distillery Row, a collection of six microdistilleries mostly in walking distance of one another. In Texas, distilleries have been preparing for visitors and adding gift shops after getting the legal go-ahead a year ago to sell to the public.

“There was no drastic, overnight change,” says Carlos Guillem, founder of DeLos vodka distillery outside Dallas and a consultant to the growing microdistillery industry. (He’s also Baughman’s cousin.) Direct sales went up, but the majority of distillers didn’t see a big surge, largely because they’re not located in urban centers.

When Guillem got into the business eight years ago, he was one of just four craft distillers in his community; the number has since grown to 20, and some are urban. “I feel it will continue to grow as the public becomes more aware and as distillers begin catering to the future public demand,” he says.

Strong support for local products is helping Capital Region distillers get their start. Gold River gin and Stratton’s bourbon were both featured at this year’s Tower Bridge dinner as part of Sacramento’s Farm-to-Fork Festival. And when Baughman’s gin first went into Total Wine stores, customers were so eager to buy the local liquor, they snatched it out of boxes before it could even hit the shelf.

Baughman is still working a 9-to-5 in the utility industry, but he hopes to create a solid business that could provide full-time work. There are easier ways to make a buck. But not too many that are as fun. “I am happy,” he says, “to do something that people enjoy.”

Spirits produced locally by Amador Distillery and Gold River Distillery are available at restaurants and retail outlets throughout the region, including Total Wine & More and Nugget Market.

Recommended For You

Shaken or Stirred?

Cocktails with local flair

Bartenders around the region have provided us with their best bets for holiday cocktails featuring gin, rye and bourbon — spirits that are now being produced locally by craft distillers.

A Mature Palate

m2 Vintners has a laid-back vibe and high-end digs, reflecting the new image of Lodi wines

At the crush pad of a custom-built winery, the 6-foot-4 winemaker in tie-dye socks shuts off the forklift, realizing he missed a call.

“I didn’t hear my phone ring,” says Layne Montgomery, 55, general manager and founding partner of m2 Vintners Inc. in Acampo.

“It’s harvest,” jests one of his volunteers. “Who has time for a phone?”

Tapped Out

Is Sac's craft beer bubble on the verge of bursting?

When downtown Sacramento’s Brew It Up poured its last beer in 2011, owner Michael Costello lost more than his business. “I lost everything,” he says. “Nobody really knows the whole breadth of it. It’s not an easy thing to go through.”

Wine Winner

How Dr. Grover Lee went from the pharmacy to the vineyard

Imagine you’re a successful businessman, but what you really want to be is a professional baseball player. You’re so sure of yourself that you begin spending nights and weekends studying and training as if Major League Baseball will soon be calling. And then they actually do, and at your first at-bat, you clear the bases.

That’s pretty much how things happened when Granite Bay pharmacist Dr. Grover Lee decided to become an award-winning winemaker.

Comments

So how does the Aunt in Iowa get a bottle?