Sutter’s Fort, the 6-acre state park in Midtown Sacramento, is an underappreciated jewel in the crown of the region’s historic attractions. That doesn’t mean it’s unpopular — it hosts approximately 85,000 visitors each year, “with 35,000 to 40,000 of those being students from 51 area-and-beyond schools on field trips,” according to Jared Jones, the site supervisor of both Sutter’s Fort and the State Indian Museum. He adds, “This year, 2,500 of those kids did overnight stays, accompanied by 1,400 chaperones.”

But the venue simply isn’t flashy, and most tours last 45 minutes to an hour, Jones says. Unlike similarly focused Western history attractions like Knott’s Berry Farm or even Disney’s Frontierland in Southern California, there are no living history characters involved in mock gunfights, no theater staging Gold Rush melodramas, no rides on burros or trains.

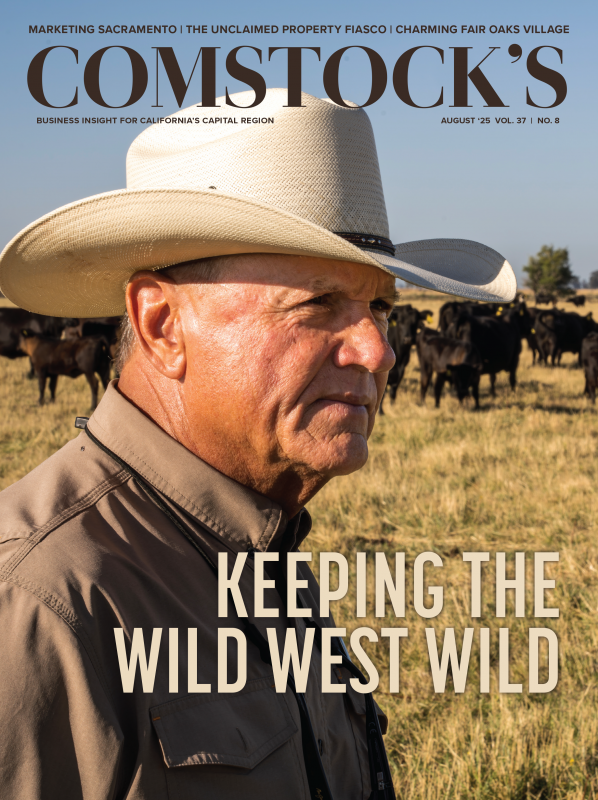

Jared Jones, the site supervisor of Sutter’s Fort and the State

Indian Museum, is 32 and has been working at the fort for 12

years.

Dreamed up in 1839 but not built until two years later by John Sutter — a Swiss developer, explorer and apparently bad credit risk who didn’t so much emigrate as flee to California just ahead of bill collectors — it was intended to be a reboot of the Garden of Eden, an ideal agriculture and trade community of growth and prosperity. He named it New Helvetia, which means New Switzerland (and is still the name of a historic district in Land Park).

It was the Central Valley’s first immigrant community. Sutter — “who came from Europe, a land of kings and feudal lords,” according to Jones — managed to grab a 50,000-acre land grant from the then-Mexican governor of what was called Alta California. He put the area’s Native people to work as though the fort was a plantation, and he was the slavemaster. That part of the story wasn’t clearly enunciated at the venue for decades. Things have changed, as we’ll shortly learn.

Authentic history

Tagging along with a couple of visiting school groups on two separate recent afternoons, this writer found it curiously refreshing to soak up their sense of excitement at the no-tech kiosks — just converted barracks from when Sutter’s Fort really was a place that housed soldiers. The central theme was two-fold: education and authenticity, goals that shouldn’t be mutually exclusive but often are for the sake of keeping antsy school kids entertained.

At a mini grist mill, the young visitors learned how to grind wheat flour to bake bread, weave textiles for clothing, make their own candles, create rope from natural fibers and — “by far our most popular attraction,” says Jones — learn blacksmithing skills at a real, somewhat recently restored workstation, whose tools and adobe decor came in 2017 courtesy of a $25,000 donation from the Sacramento Pioneer Association. That group was founded in 1854 by Sacramento residents who had the rare ability to glimpse the future and know they were living through times that would someday be historically significant, Jones says.

On a subsequent visit, which takes place on a hot Wednesday afternoon with nary a school group in sight — Jones says “mid-February through the beginning of June is when we get the majority of kids” — the fort is figuratively unplugged. It’s up to date on ADA requirements, but the sole remaining structure from its inception — a two-story adobe building Sutter used as his offices and home — lacks elevators or ramps, in keeping with historical veracity.

Meanwhile, a 40-ish dad wanders around with his tween-age children, serving as an unofficial tour guide. “I came to this place about six times when I was a kid,” he says. “I know it by heart. But I kind of miss the people dressed in historic clothing.”

Encountering “living history” characters — in this instance, people dressed up as pioneers, 1800s soldiers or the Indigenous people who worked the fort and surrounding lands — is no longer part of the Sutter’s Fort experience. The changeover occurred in the early 2020s after years of complaints from Native American tribes compelled the state to rethink the destination’s own character.

“The history we were dispensing to the public for decades was one-sided,” Jones says as he guides a visiting writer through the buildings but, more importantly, the transition of Sutter’s Fort. “It wasn’t very candid about how the Indigenous, Native tribes were treated, which sometimes was as employees but sometimes as slaves.”

Jones, who’s 32 and has been with the park for 12 years, started out as an intern here, wrote his master’s thesis on its history and produces the facilities’ social media videos, most of which can be viewed on its dedicated YouTube channel. A frequent tour guide, he has a commanding presence and deep affection for the fort — but also knows that its complicated history needed to be more honestly presented.

In 2021, a document called the Interpretation Master Plan was prepared with the consulting assistance of seven local Native American tribes to help the state find its way toward presenting a more balanced picture of its origins. The general feeling was that Sutter’s Fort’s heritage had been literally whitewashed — that, in fact, white settlers, prospectors, historians and teachers were promulgating a skewed view of Sutter, both the man and the fort.

The plan’s adoption and implementation has been largely successful, Jones says. It asserts that Sutter’s Fort “will become a place of academic discovery, discussion, perspective, reflection, and most of all accuracy in communicating the history of California. Previous interpretive principles will remain a part of this institution’s history, but we move forward into a new reality. Discovering and understanding complex cultural histories within California requires a new approach that relies less on living history concepts and more on critical analysis of history to deliver thematic experiences to visitors.”

Don’t let the bureaucratic language put you off. More than ever, Sutter’s Fort is a regional, interactive treasure, one that mixes timeless learning with newly admitted truths.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Fairytale Town Is Still Magical at 69 Years Old

No thrill-seeking rides, just imaginative fun

Once upon a time — 1959, to be precise — Fairytale Town opened at

3901 Land Park Drive in Sacramento, just four years after

Disneyland debuted in Southern California. Almost immediately it

was acknowledged, year after year, as one of the region’s top

five family amenities — and still is.

At 123 Years Old, McKinley Park Is the Still-Thriving Glory of East Sacramento

The park features the largest rose garden in the Capital Region

This isn’t just any park. The McKinley Park rose garden is the setting for countless al fresco weddings, confirmations, quinceañeras and private soirees. It also provided a stunning backdrop for the scene in Sacramento native and filmmaker Greta Gerwig’s “Lady Bird,” in which the two young lovers own up to their emotions.

Anna Judah: Far More Than Theodore Judah’s Victorian Housewife

Through her artistry, she brought the transcontinental railroad to life — before it was built

You wouldn’t know that a tragic love story led to the railroad that connected the East and West coasts for the first time.

The Violent, Bloody Folsom Prison Escape of 1903

New book details a dark time in the prison’s history

The prisoners made makeshift knives, or shivs, and used stolen razors during their siege. One prison guard died, and two were injured.