It was Arnold Schwarzenegger at his most persuasive: The then-California governor laid out an audacious vision, borrowed from legislators, of the Golden State leading the world in fighting the damaging effects of climate change.

The proposal’s sweep was as expansive as the Governator’s sculpted chest. The Global Warming Solutions Act passed on the last day of the legislative session in 2006, with a promise that its suite of carbon-cutting goals would not only do no harm to California’s economy but would expand it, ushering in green jobs and attracting investment.

The law also required state agencies to consult with experts to provide periodic analysis of any effect on California’s economic health. But those infrequent and complex reports have merely proved why economics is the dismal science: There’s fuzzy math on all sides.

California, the world’s fifth-largest economy, spends billions of dollars every year to support its dozens of climate-change programs but has trouble demonstrating whether the promise of the law that spawned them has been kept.

Though a separate state law requires economic analysis of major regulations, there is no requirement for a retrospective review. Environmental authorities calculate projections rather than audit the past, a problem identified by the Legislative Analyst’s Office, which is preparing its own analysis for release later this year.

So it has been virtually impossible to tell whether the state’s regulations to reduce industrial emissions, its demand that utilities use renewable energy and its push for residential solar panels have saved consumers money or added costs, driven businesses out or created new ones.

Schwarzenegger has been steadfast in saying the environmental laws he helped put in motion have outperformed expectations.

“We were told so many times by business leaders when we passed these environmental laws that businesses were going to leave the state, that the unemployment rate is going to rise, and it would be the end of our economy,” the former governor said in a speech in Vienna in June. “Quite the opposite has happened.”

Among the promised benefits were that gross state product would increase on the order of $7 billion in 2020, and 100,000 new jobs would be added.

But with 2020 only 16 months away, it’s unclear whether those numbers will pan out. The state has produced no reliable evidence linking growth so far to climate policies. And economists say it’s nearly impossible to parse whether California’s good fortunes are the result of the environmental laws or despite them.

Even Mary Nichols, head of the California Air Resources Board, which developed the blueprint for implementation of the original law and those that have built on it, has expressed frustration. In a meeting last year, she appeared dissatisfied that the agency’s broad claims of economic benefit weren’t reflected more clearly in its projections, particularly concerning the state-run cap-and-trade system that limits how much companies are permitted to pollute.

Considering the stakes, hers was a breathtakingly candid admission: “We still don’t have the ability to capture, in any kind of models that seem to be available to us, at least some of the elements that we are intuitively claiming,” Nichols said.

“And I’m wondering,” she went on, “if we have failed, in some way, to…do the kind of research that needs to be done, whether there’s a way to get that kind of research done, so that we’d have a better basis to use economics in decision making.”

The board’s most recent projections are for the year 2030, outlined in a 132-page report. With most factors weighed, the document says, California’s climate policies could reduce the economy by .03 percent—a negligible effect, according to economists.

And California appears well on the way to meeting its nearest goals for cutting greenhouse gases: reducing them over the next two years to what they were in 1990.

Still, said James Bushnell, an environmental economist at the University of California, Davis, “I think we oversold the argument this was going to cause growth.”

“All we can really say is that the California economy is growing and doing well” right now, said Bushnell, who has twice participated in state review panels on the economic impact of environmental policy. “Everything else I would take with a huge boulder of salt.”

State Sen. Kevin de León says jobs growth can be traced directly to California’s continuing climate policies.

“Coming off the worst economic recession we had, we created upwards of 500,000 jobs in the clean-energy space. That’s 500,000 jobs that didn’t exist were it not for the policies of the Senate, Assembly and the governor,” said de León, a Democrat from Los Angeles who is running to unseat U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein in November.

His claim is an oft-cited statistic. But many researchers say that measurement doesn’t distinguish between new jobs that add to the workforce and jobs that merely supplant old ones.

Researchers at UC Berkeley estimate the state’s mandate that utilities get half of their power from renewable sources by 2030 will have created as many as 429,000 construction jobs from 2015 to 2030.

Indeed, labor unions and trade groups cite employment bumps whenever renewable-energy projects or other green mandates are rolled out. But much of that work is temporary.

The tricky task of projecting employment was noted by the legislative analyst in 2010, when it found that the air board “was not able to provide reliable estimates of the jobs impacts.”

One mandate of the 2006 law was that the state consider the “maximum technologically feasible and cost-effective reduction” of greenhouse gases. That caution was meant to protect California companies from suddenly absorbing undue burdens to comply.

Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable, which represents major employers in the state, said he supports the climate goals and agrees that so far the implementation of related policies hasn’t harmed the economy.

But he added that companies have spent billions undertaking expensive changes to processing plants and manufacturing facilities in order to lower their emissions. And business leaders are concerned about what happens as greenhouse-gas restrictions become even tougher.

“They understand that the next round of implementation could have Draconian impacts to cost,” Lapsley said, adding that some companies are reluctant to relocate to the state because of that uncertainty.

He declined to name any of those firms. And some experts say there’s often a host of reasons, including high taxes and soaring housing costs, that companies shy from establishing themselves in California.

State officials insist that California has wisely positioned itself to capitalize on the economy of the future, and they note that technology firms are busy developing next-generation batteries and innovating other carbon-free responses to climate change.

Many benefits derived from California’s climate policies come at a price. The Air Resources Board says the state has spent more than $8 billion in the last four years to keep the programs running.

In fiscal year 2017-18, the Legislature and Gov. Jerry Brown appropriated more than $2.7 billion to support greenhouse-gas reduction. The current budget allocates $1.5 billion. Nearly $53 million goes to the air board.

State support takes many forms. Since 2009, for example, California has offered rebates on the purchase of electric or hydrogen-fuel vehicles, which may cost more than others.

That’s part of an effort to meet the governor’s target of putting 5 million electric cars on California roads in the next 12 years. The state plans to put $1.4 billion into electric-vehicle infrastructure and more rebates over the next seven years.

Officials say these are all monies well spent, that every dollar used to fight climate change attracts $6 of investment. That figure reflects, in part, investment generated by state-funded grants to help companies retrofit or buy new emissions-reducing equipment.

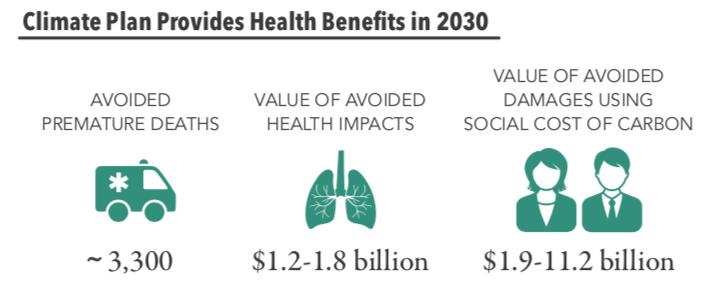

Officials also say climate laws will save the state as much as $11 billion in “avoided social costs”—lost productivity and even public health outlays—by 2030.

And the state says businesses and consumers alike will save money over time, through lower costs for power. For example, the mandate that beginning in 2020 new homes must have solar panels could add as much as $10,000 to house prices, but officials say those sums can be recouped over years of ownership.

In 2014, the board convened a symposium of esteemed economists, put them in a room for two days and asked them to devise the most effective formula to measure the economic effect of California’s environmental policies. They failed, disagreeing about which model to use, which assumptions to include and even about the advisability of making projections so far into the future about something as volatile as California’s nation-state economy.

The absence of any consensus then or since suggests how difficult real analysis is. “It’s an issue that we’ve been wrestling with,” said Emily Wimberger, the air board’s chief economist.

“There are a million things influencing these numbers,” said Chris Thornberg, founding partner at the Beacon Economics consulting firm. The idea that it’s possible to measure the influence of climate policies “is ridiculous.”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.