The person who finds the cure for HIV will have their name etched in medical history.

The breakthrough would alter the very fate of millions of sick and dying people around the world. It would be the kind of discovery that could change the course of humanity, restore families, transform Africa. It would come with notoriety and fame. Perhaps an untold financial windfall.

It’s a hard pill to swallow for one man who has spent 40 years of his life chasing a cure. Watching his friends die of AIDS. Grinding away thousands of hours in laboratories from Vienna to Los Angeles. A cure for HIV, built upon decades of his work, could very well be proven this year. Yet Dr. Gerhard Bauer’s name may be little more than a footnote in the arcane medical journal that publishes the breakthrough.

This is the story of curing HIV.

The Meeting

The meeting that severed ties took place on a Monday last November. Three UC Davis scientists sat around a cluttered office inside the university’s Institute for Regenerative Cures. Between them, nearly 75 years of HIV research, their impending proof of a cure and a very palpable tension.

Clinical trials to test their treatment will start within months, and by the end of this year we could know whether these scientists have in fact developed a method for creating a wholly HIV-resistant immune system in human patients. Their goal will be to eradicate an infected immune system and rebuild it with one impervious to HIV. Six months from now, they hope, the world could see its first cure for the human immunodeficiency virus. But what happens after that may prove more complicated than the science itself.

The Cure for HIV — A Primer

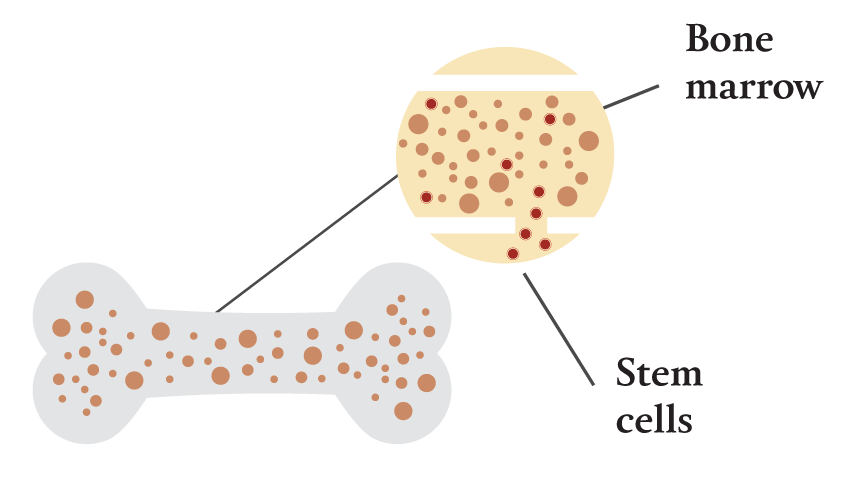

The human immunodeficiency virus infects cells of the immune system. All of those cells are created from blood-forming stem cells that originate in the body’s bone marrow. These stem cells are present at birth, and they produce all of a person’s blood and immune cells for life.

In the past 20 years, scientists have been able to prove, through stem cell gene therapy, that blood-forming stem cells can be genetically modified to block HIV infection or stop it from replicating in the body.

But to this point, scientists haven’t been able to cure anyone. They haven’t been able to provide enough of the modified cells. That’s about to change.

The UC Davis Institute for Regenerative Cures is located in a building that once housed livestock for the California State Fair. It’s now the $62 million center where physicians, research scientists and biomedical engineers develop cellular and gene therapies for diseases ranging from Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s to sickle cell anemia and osteoporosis. It’s also where an Austrian-born scientist in his late-50s and a virologist in his mid-30s have been waging their war over who should receive credit for the scientific breakthrough.

If their hypothesis is correct — and they’re certain it will be — their federally approved clinical trial could be the perfect catalyst for two intensely talented colleagues to form a company, commercialize their innovation and take the enterprise public.

But they’re not speaking anymore.

The Beginning

Sex between people of the same gender has been legal in Austria since 1971, but in a country deeply seeded in Catholic tradition, homosexuality remained strictly taboo well into the 21st century. Such was the environment Gerhard Bauer entered when he was born in the countryside outside Vienna to a mechanical engineer and an elementary school teacher in the 1950s.

1.) Treatment will start with an HIV-positive lymphoma patient

“They had the same kind of anti-gay laws that they have now in Russia. Public assembly by gay people was forbidden, and publication of anything gay-related was forbidden,” he recalls in a smooth, moderate accent. “I was part of an illegal gay organization at that time — with a different name, Robert Wagner — because you would have been arrested. They arrested a 19-year-old because he put a flier out for our community Christmas party. That was 1986.”

It was only a few years earlier, shortly after Bauer graduated from medical school at the University of Vienna and acting school at Max Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna, that he took a day job managing HIV test kits for the Austrian Ministry of Health. It was a good way for an aspiring actor and radio personality to pay the bills, and it was there that Bauer learned the business of managing laboratories.

“I found that HIV was much more widespread than people had anticipated. Suddenly, people that I knew started to get sick and to die,” he says, withdrawing his spectacles and rubbing his eyes. He straightens his tie. “It felt horrible for me. I saw these people dying, and you couldn’t do a thing about it. It accumulated to 15 of my friends dying, so I said, ‘I have to do something about it. I want to find a cure for HIV.’”

2.) The patient will have a blood draw, which will extract bone

marrow stem cells.

He was 28, bright, self-assured and armed with a 1988 article about intercellular immunization, which supposed that adding modified genes to stem cells could make a person HIV-resistant.

“I talked to a lot of people at that time who called themselves scientists, and they scoffed at me. Laughed at me,” he says, with a tone almost mocking. “They said there is never going to be a cure for HIV, for AIDS. They said it’s what gay people get; its a punishment from God.”

So he packed his vintage cameras and his record collection of 1920s dance music and moved to America, the one nation in the world he believed could make his dream possible. He was offered a position as a research scientist in a laboratory at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, where he studied the transmission of HIV from mother to child, the behavior of antiretroviral drugs and the early detection of HIV in infants. His influence and work there were important enough to attract the attention of Johns Hopkins University, which called in 1992 to offer him a research post.

3.) The patient will undergo chemotherapy to wipe out all

remaining bone marrow cells, including HIV-susceptible cells,

providing a nearly clean slate from which to regenerate the

immune system.

“Something serendipitous happened. By chance, somebody there was trying to develop stem cell gene therapy for HIV. I said, ‘Cool, I want to do that.’ I have always wanted to do that. And nobody else knew how to do it anyway,” he says with a broad, knowing smile. So he packed his bags and moved across town.

The hypothesis scientists were applying at the time was new, and it worked like this: Blood-forming stem cells are responsible for creating all of the blood cells in the body. If you can collect those cells, manipulate the genes within those cells so they reject the human immunodeficiency virus and then put those cells back into the body, they should replicate to create an HIV-resistant immune system.

Bauer is what the scientific community calls a basic researcher. He’s a fact finder and a creator of concepts. Translational scientists, on the other hand, take that basic research and develop the products and experiments that make it safe and usable. And then you need somebody who is crazy enough to put that product into a patient. That’s the clinical researcher.

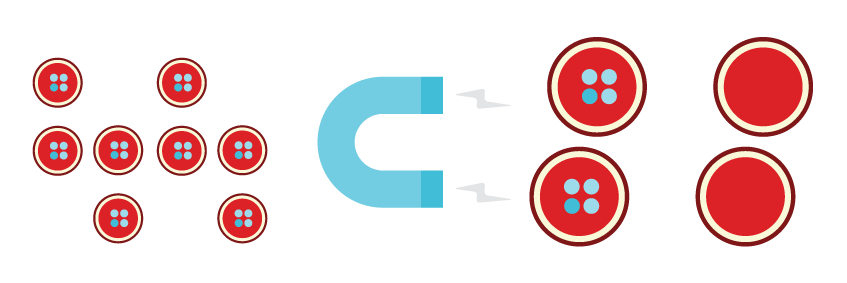

4.) To separate the modified stem cells from the blood,

scientists use a magnetic bead to attract any cells that contain

the marker gene. Now, they have a purified pool of HIV-resistant

bone marrow stem cells.

Successful gene delivery requires an efficient way to insert DNA into cells. Scientists refer to these DNA delivery vehicles as vectors. During Bauer’s time at Johns Hopkins, he developed the procedures necessary to insert vectors into bone marrow stem cells. And then on paper, he could show the result: HIV-resistant stem cells. From Baltimore he moved to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, and it was there that Bauer met Jan Nolta, a then-Ph.D. student who is now the director of the Stem Cell Program at the UC Davis School of Medicine. She had developed similar methods for inserting genes into bone marrow stem cells for the treatment of genetic diseases. At that time, Nolta and Dr. Donald Kohn, the attending physician in the pediatric bone marrow transplant program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, had just treated the first child in the world — the immunodeficient “Bubble Boy” — with stem cell gene therapy.

Using the same principles, Bauer tried developing a similar method for treating HIV. “So I sat in the basement where my lab was for many, many, many, many weeks and improved the methods of gene therapy and developed all the data necessary to go to the FDA and tell them we want to do clinical trials,” he says.

That trial was approved, but no cure was established. Something was missing, but Bauer and his work were at the forefront of the science.

5.) UC Davis scientists, using stem cell gene therapy, will add

four genes to the patient’s bone marrow stem cells. Three of

those genes will combine to make the cell HIV resistant. The

fourth is a benign marker that makes it possible to sort the

modified cells from those that did not receive the extra genes.

For more than a decade, a cure eluded scientists and patients alike. Bauer and Nolta both relocated from UCLA to Washington University in St. Louis. Bauer had become one of the nation’s premier experts on the management and development of Good Manufacturing Practices facilities — the laboratories in which highly sensitive medical products, such as modified stem cells, are created. At Wash U, he designed what would become one of America’s top GMP facilities, but support for Bauer’s true mission waned.

“They would not allow me to work on stem cell gene therapy for HIV,” he says. “They didn’t like it. And suddenly our program was renamed from Stem Cell Program to Hematologic Development and Malignancy Program. Then we were told that we had to stay in the closet because otherwise maybe the football team would not be funded.”

At that time, the mid-2000s, the topic of stem cells — specifically, embryonic stem cells — began to receive increased media scrutiny, and in the heart of the Bible Belt, the science was aggressively scorned.

6.) The patient then receives a blood infusion of the genetically

modified cells through an IV. Once the stem cells enter the body,

they will return to the bone marrow and begin to regenerate an

HIV-free immune system. HIV can sometimes remain hidden in areas

of the body, such as the lymph nodes, but facing a resistant

immune system, the virus should not be able to replicate.

By six months after treatment, scientists should know whether the treatment worked, but to be able to proclaim that someone is cured will take years due to the virus’s ability to remain latent.

“I was invited to talk (on the radio) about the benefits of stem cell research,” Bauer recalls. “There was a caller that said, ‘I am in a wheelchair, but I don’t want to have babies killed in order for me to get out of the wheelchair.’ I tried to say, ‘You don’t need to have babies killed! That’s not what we’re doing.’”

After the talk show, Bauer received threatening letters from churches and rotten vegetables at his front door. His yard was vandalized. At that particular time, California’s Proposition 71, the California Stem Cell Research and Cures Act, passed voter approval, making stem cell research a state constitutional right and allocating $3 billion to research and facilities. UC Davis received a chunk of that money, and Bauer received a call from the university asking if he would like to come build a GMP facility.

“I was seriously contemplating that, but I had just built this other facility and Dr. Nolta had just established herself,” Bauer says. “But when the anti-gay billboards went up on the freeway, I signed the contract. That was the last straw.”

Bauer arrived at UC Davis in 2006, and Nolta was just months behind him. Quietly, in the decade since, a team of scientists inside that lab has continued to research and test methods for treating HIV with stem cell gene therapy. They’ve published papers and books, given lectures to doctors and researchers across the country and, finally, they think, have identified the missing link.

Bauer, over french fries and iced teas at The Firehouse Restaurant, poised and smartly dressed with tightly-trimmed hair and pencil mustache, launches into the find. He’s exuberant and emphatic, expertly explaining the newest treatment method and the culmination of his life’s work. Occasionally the conversation shifts to his rare-film collection, which includes a mint 35mm print of the first feature length 3-strip Technicolor movie ever made.

“If this [clinical trial] works, I will found a company immediately; spin it off from UC Davis,” Bauer said in October. “You need to have a company behind it that brings it out to all of the people. This is America, goodness gracious; we have industry here. We can make it so that people can have access to it and that it’s reasonably priced with quality control. The manufacturing price will go down when we develop a machine that can do it. I’ve talked to certain manufacturers already who would manufacture a disposable (version).”

Days after that claim, a young scientist named Joseph Anderson sat down to type an exasperated email, demanding to know why Bauer was the subject of a story, purporting to have discovered a possible cure for HIV. Bauer has nothing to do with it, Anderson claimed. He’s exaggerating and robbing credit from the man who’s truly to thank — Anderson himself.

Dr. Joseph Anderson, HIV disease team, UC Davis Stem Cell Program

(Photo by Kyle Monk)

That initial communication was unexpected, and when asked about Anderson’s allegations, Bauer said, “It was a group effort to get all of the regulatory hurdles cleared to start the HIV gene clinical trials. But [Anderson] is obsessive, possessive. He will deny anyone else’s involvement. He’s an egotist, you know, so everything is his.”

The Breakthrough

In 2008, scientists at UC Davis began experimenting with immunodeficient mice. By transfusing the mice with human bone marrow stem cells, the researchers were able to develop a human immune system within the animal. From that point, they could infect the mice with HIV, test anti-HIV drugs or, in this case, the stem cell gene therapy that could cure the virus.

As before, the tests worked — sort of. After treating the mice with stem cell gene therapy, all of the mice resisted HIV infection. But there remained a problem, the same problem seen for decades in patients: The gene-modified cells could ward off the virus, but the animals weren’t cured. It was a problem of quantity.

“I saw 15 of my friends die. I worked all my life for this. I rather want this. But if somebody else wants to run with it, let them run.” Dr. Gerhard Bauer, Good Manufacturing Practice lab director, UC Davis Institute for Regenerative Cures

Not all of the stem cells being placed into subjects’ bodies over the years have been HIV-resistant. In fact, only a small, random portion of the cells — typically much less than half — can be successfully modified. So at the core of the treatment has been a lack of critical mass. If the proportion of HIV-resistant stem cells is not substantial, the body will still replicate the virus.

So a young translational scientist named Dr. Joseph Anderson decided to try something new. He masterminded a selective vector — a sort of indicator called CD25 — that allowed the scientists to identify the engineered cells from the normal cells.

“We can only get between 10 and 60 percent of the cells genetically modified; it just happens on a cell-to-cell basis,” Anderson says, casually propped in a swiveling chair in a back aisle of the Institute for Regenerative Cures. “So my lab developed this selective vector that allowed us to select the genetically modified cells out of that mixed population, so when we give the cells back to the patient, they get a nearly 100-percent pure population of protected cells. So all the new cells in their body will be resistant to HIV, instead of just a fraction.”

It worked. After receiving the pure population of genetically modified, HIV-resistant bone marrow stem cells, the mice were incapable of replicating the virus. Anderson, just three years after completing his Ph.D. at Colorado State University, had cracked the code. He explains the method with cautious, exacting language. He is a man of detail, clad Zuckerberg-style in a weathered hoodie and a pair of well-worn denim.

“A lot of things that work great in the lab and in the animal models don’t translate to humans,” Anderson says. “I want to see that it works before we start telling the whole world about it, but this is probably the best thing so far in HIV stem cell therapy and has the most potential to cure patients. But we haven’t cured anyone yet.”

That time may be coming. Anderson, Nolta, Bauer and clinical researcher Dr. Mehrdad Abedi have received approval from the FDA to begin the first phase of human clinical trials using Anderson’s patented CD25 vector. In partnership with the University of San Francisco and the University of San Diego, the team at UC Davis will begin seeking HIV-positive lymphoma patients who are in need of a bone marrow transplant and who want to test the safety and efficacy of this breakthrough.

“A lot of things that work great in the lab and in the animal models don’t translate to humans. I want to see that it works before we start telling the whole world about it, but this is probably the best thing so far in HIV stem cell therapy and has the most potential to cure patients. But we haven’t cured anyone yet.” Dr. Joseph Anderson, HIV disease team, UC Davis Stem Cell Program

Participating patients will receive a blood draw. They will then undergo chemotherapy, which will eradicate the infected immune system and the remaining bone marrow stem cells. During these weeks of treatment, Bauer and his employees will take the stem cells from the blood draw into the GMP facility and genetically modify them to be HIV-resistant. During that process, Anderson’s selective vector will mark the engineered cells, and once chemotherapy has been completed, the patient will receive an IV infusion of those cells, which will replicate in the body, creating a clean and healthy immune system free of HIV — for life.

“Its paradigm-shifting work, and everybody wants to be the hero,” Nolta says. “The drive is to make a difference, that’s why we do what we do. It’s high stakes, and there’s a lot of passion. For Gerhard, this has been his life’s mission, his legacy.”

The Meeting

The meeting in November put a human face on a scientific process. The meeting was about spinning off a company when and if the human trials produce a cured patient: how it would be structured, the appropriate timing for launching such an entity, funding, manufacturing and how Bauer, Anderson and Nolta would each be involved. The meeting was also about turf.

“Gerhard starts saying all this stuff about how he went to a lawyer and that he’s going to be CEO and call it Bauer Lab Group,” Anderson says, voice rising to a heated whisper inside the quiet lab. His hands are shoved into the pockets of a navy blue hoodie. “What are you thinking? This is not your work. Why are you making these decisions? He’s trying to do this stuff on his own, saying we’re going to run it out of his house.”

“If it works, I am going to withdraw. He wants to do it on his own, so he can do it. He’s becoming egotistical, and I want nothing to do with that. All I want is the publication. I want my name on it. That is good enough for me. I’ll walk away.”

Dr. Gerhard Bauer, Good Manufacturing Practice lab director, UC Davis Institute for Regenerative Cures

There are two product patents wrapped into this project. One is a joint patent naming all three scientists and held by the university. The second patent is for that critical CD25 selectable marker, and only Dr. Anderson is named on that one. In order for anyone to start a company using the method put forth by the UC Davis disease team, the selectable marker — or a brand new, similar product — would be needed.

“The company is based off of my work. He wants his name in the company name. Why?” Anderson says, head shaking. “Just because he worked on it 15 years ago in other people’s labs — not his own lab — and has had friends who have died from HIV, he has this self-entitlement like this is his work. Yes, its been a dream of his, he’s passionate about the disease. But you can’t just take it and promote it and say that it’s yours.”

Anderson said as much to Bauer. And with that, Bauer retreated.

“If it works, I am going to withdraw,” Bauer said later, his voice dropping almost to a mutter. “He wants to do it on his own, so he can do it. He’s becoming egotistical, and I want nothing to do with that. All I want is the publication. I want my name on it. That is good enough for me. I’ll walk away. I would never compete with him, for the sake of the people who need the cure. I have high ethics. I saw 15 of my friends die. I worked all my life for this. I rather want this. But if somebody else wants to run with it, let them run.”

He pauses, pensively.

“To have your name forever associated with what you did, that’s the bigger reward. I look back on my publication list, and I have so many publications that are really worthwhile. I think it’s what I am the most proud of,” he says as if he’s already gone.

“Actually, what I would really like to do is run out of my garage a little service for people to have their films digitized, even 35mm,” he says, regaining life. “I have the equipment, and I want to use it. I want to do something nice for other people. And I want to form a band. I’m a drummer, and I would like to play the dance music of the 1930s and 1920s. That is what I would like to do. My own band.”

As for the clinical trials, a cure and a company, only the future will tell. Patients could be accepted and begin treatment as early as this summer, though the disease team is still awaiting approvals from a number of university boards and committees. Nolta and Anderson have met with business advisors at UC Davis, they’ve applied for grants and Anderson is pursuing his masters in clinical research.

If all goes according to plan, preliminary trial results could arrive by year’s end. Patients will undergo years if not decades of monitoring to follow their progress and long-term health. If successful, non-lymphoma HIV patients might have a shot at a cure before the next presidential election.

Comments

As a nuclear Pharmacist I have read this article thoroughly and believe surely we are now closer to a cure than before Let the clinical trials start as soon as possible. CAUTION: Please dont spoil all this work by fighting over ownership before the fruit gets completely ripe

Seriously, this is bigger than an ego. Why cant both names be attached to this?