The Instagram grid of lifestyle and travel photographer Alina Tyulyu has taken on a new look since late February, when Russia first attacked Ukraine. Her page, once soaked in California sun with glimpses of chic resorts and alfresco meals of oysters and wine, now tells the sobering story of life in war-torn Ukraine.

A family is reunited at the Poland-Ukraine border in Medyka.

Tyulyu’s photos, especially her Instagram Stories, which function as daily photo diaries, are exceptionally visceral. Each picture brings with it a distinct perspective and feels both expertly composed and impulsively captured. The first story from one recent day in Ukraine shows two women frolicking in a flower field where honey-hued blooms dissolve into a sky streaked with sunshine. The second frame, set in the middle of the day, depicts a farm picnic in the sprawling countryside, a bucolic paradise with silken baby lambs. In the cool hues of evening, we see her elderly host wave goodbye from his farmhouse, framed by the back window of Tyulyu’s car as she drives to her next destination.

Not all the images are so idyllic. Depending on the circumstances, they run the gamut from somber (gray, crumbling neighborhoods ravaged by explosions, often with foreboding messages spray painted on doorways) to anxious (weary crowds with worried expressions lined up for humanitarian aid or en route to what they hope will be a safe haven). Lately, reprieve has come in the form of bright bursts of tulips as spring blooms in Kyiv. Aside from scenes like these, many of Tyulyu’s images are portraits of Ukrainians in rare moments of calm; some smile warmly, others appear to be putting on a brave face.

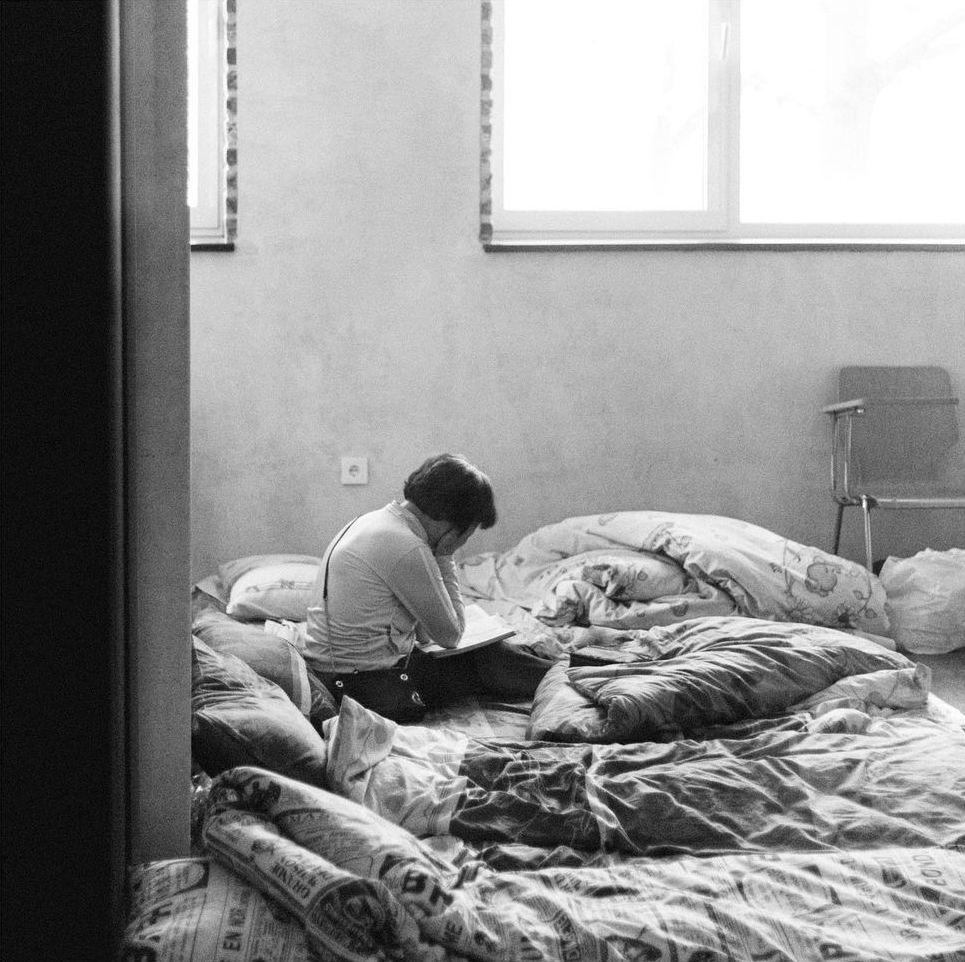

“People here are 100 percent willing to talk, and I feel like they just need to talk,” Tyulyu says on a FaceTime call from the floor of a bare room in Ukraine’s Zakarpattia Oblast region where she’s sharing a bunk with another volunteer. “That’s one of the biggest things here, too, is we’re trying to offer actual emotional support. A lot of these people are going through major emotional stuff.”

Tyulyu learns people’s stories as she travels through war-torn

Ukraine, like this man who shared with her the damage to his home

in Bucha.

Tyulyu feels confident her shift toward ad hoc reporting is important, but admits it’s been a challenge to “write the story behind the actual shot.” With a camera, “You don’t filter things through your heart, you filter them through your lens,” she says. “Because you have a job, right. I think that keeps me going. … I’m like, OK, I have a job to give these people justice and share their story in the right way.”

Thanks to their new van purchased with donations, Tyulyu and her

fellow volunteers were able to donate food, water, survival

supplies, hygiene kits and medicine to refugees in her hometown,

Druzhkovka.

“This is always a sad sight,” Tyulyu writes in her Instagram

caption. “Civilians would write ‘people live here’ and ‘kids’ on

their gates in hopes of Russians having mercy and passing their

home. More times than not, these homes became targets instead.”

How are you going about your interviews with the people you photograph in Ukraine? Is it spur of the moment or is it more planned out? Or both?

There are some that are kind of intentional, but a lot of them … people just want to talk. I speak fluent Russian. I understand Ukrainian, but I don’t speak Ukrainian very well. It’s kind of weird — I’m from the eastern part of Ukraine, which is right by the borders, so I grew up speaking Russian. But the thing is, because of the war, everyone’s bringing out their native tongue, so everyone’s intentionally trying to speak Ukrainian just for the sake of everything that’s happening.

A Ukrainian woman named Luda stands in front of her home in Kyiv,

Ukraine, recently ravaged by bombs. Tyulyu says Luda and her

family sealed the neighbors’ windows and cleaned so when the

owners returned, “it wouldn’t be so bad.”

“Larisa // From Mariupol,” reads Tyulyu’s Instagram caption.

“Honestly we don’t even have to ask what their story is anymore

the moment we find out where they are from. Anytime anyone says

Mariupol, Kharkiv, Dnipro, Kyiv… there’s usually a pause. A

moment of silence.”

Can you describe the response from your Instagram community?

I think the majority of the community that follows me are actually the Slavic community. A lot of my friends are from Ukraine or from Russia. All my Russian friends that live here are completely supporting Ukraine. They’ve been donating towards the cause and are very helpful and very kind. So I think I already kind of had the advantage of having already a community that’s understanding and that’s kind and they’ve been huge on reposting and sharing.

This young girl recently fled a risky area with her mother and

baby sister after spending a month in an underground shelter.

When did you move from Ukraine to the United States? Do you have any memories that make you particularly able to relate to what you’re going through now? And to some of the people you come into contact with?

We came as refugees in ’99. We moved to California because there was a pretty big Ukrainian population. And so we came to Sacramento, and we have been here since. We also were very broke for a very long time, until all of us really started working on our own. So it wasn’t until 10 years ago that I started actually actively buying tickets and just kind of going out there for periods of time.

The photographer stands amid a bright burst of flowers in

Ukraine.

You cover so many styles and genres like lifestyle and travel, and now you’re basically a documentarian. But it all shares this very dreamy, light look. Although it’s airy, it still looks rich, and you never strip the color away. How did you develop your signature look or editing style?

I put in a lot of work into getting my settings right before I take the shot. And I don’t rely on filters anymore. I try to go for the natural tones. I mean, obviously, I pick and choose, there’s a lot of photos that I want to post, but I’m like, it doesn’t fit my style, so I’ll do Stories for it. But I think just kind of focusing on the true colors has been my focus in general.

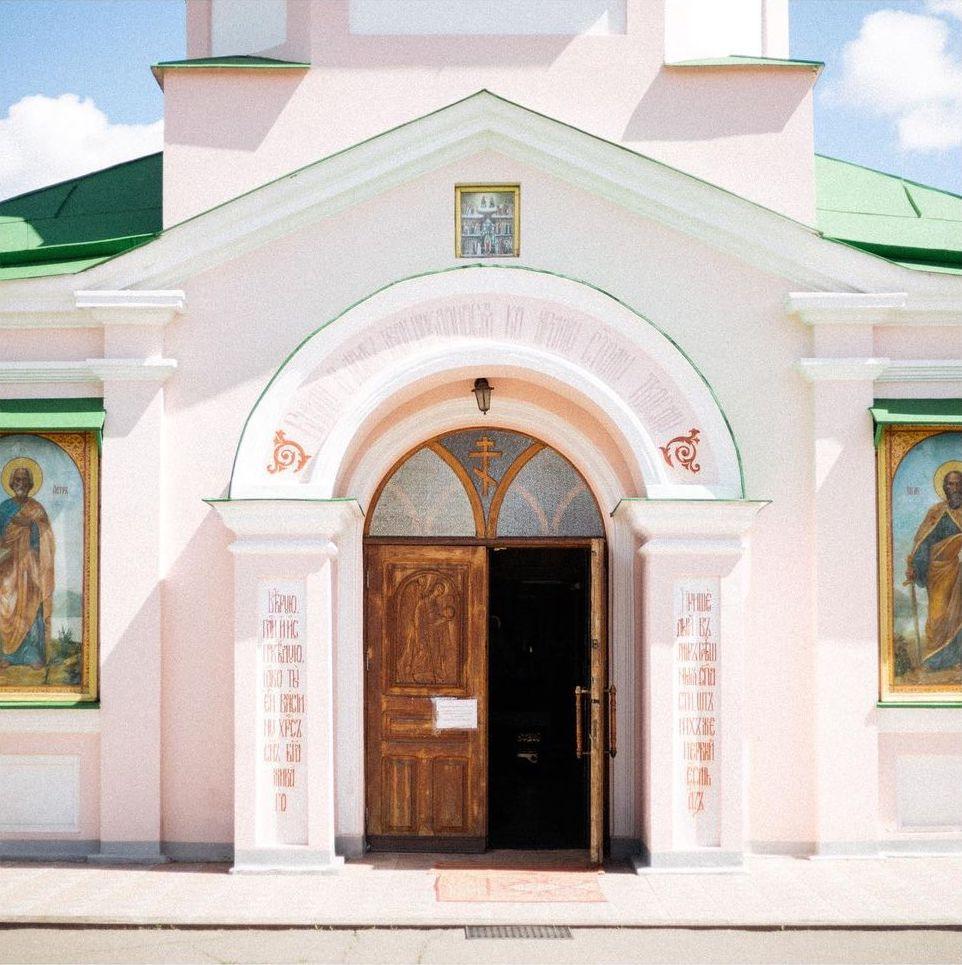

Tyulyu captures movement and contrast against a church in

Ukraine.

How did you make a space for yourself in lifestyle and travel photography? How did you build your portfolio to nab prestigious clients like Proper Hotel and publications like Condé Nast Traveler?

My work with Condé Nast, for example, came through Faust Wines, which is one of my favorite wineries in Napa. When Condé Nast reached out to them about writing about them and stuff, I was one of the first people whose names they sent. And then the photos that they picked, I was like, shoot, this photo is my favorite, but it’s not actually at the winery. So I’m over here freaking out that I’m not representing the winery properly. So I reached out to the winery, and I was like, “Hey, are you guys good with this?” And so we all take care of each other. And I think that’s kind of the valuable part. …

Tyulyu captures the vivid pastel hues of a church in Mykolayiv.

I feel like if you just take care of people, they’ll take care of you. And I don’t mean it in a way of like, do things with the intention that people are going to do something for you afterwards. … I tend to under promise, and then over deliver a little bit. I try to take care of my clients, and they’ve been so kind and so loyal to me as well.

Edited for length and clarity.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Nancy Sayavong

The Roseville-based sculptor uses woodworking techniques for both art and remodeling

As a woodworker and metal fabricator, Nancy Sayavong uses her

training both for art and remodeling jobs. Her work is

interested in the contrast between the romantic ideal of the

home and its lived reality.

Art Exposed: Tasha Reneé

The local potter on the hazards of ceramics and making peace with impermanence

Tasha Reneé sells ceramics independently and through plant shops

and home decor businesses and is currently pivoting to teach

others through private lessons, workshops and classes.

Art Exposed: Jonathan Joiner

How a filmmaker and creative director mines the past for inspiration to create fantastical objects, stop-motion video and playful GIFs

Jonathan Joiner finds inspiration in retro-futuristic gadgets,

movies and “practical things.”

Art Exposed: Sarah Marie Hawkins

Multimedia artist Sarah Marie Hawkins uses a variety of methods

to tell not just her story, but the stories of many women.

Art Exposed: Deborah Pittman

A professional clarinetist broadens her creative output with

ceramics, writing, filmmaking, multimedia performances — and

puppets.