The delicate watercolors lining the wall feel so peaceful and tender that the subtle horror they suggest is almost invisible. Almost. The works appear as sanguine double exposures. A dour little girl inside the frozen smile of a Raggedy Ann doll. A sleeping man sitting upright, barely contained in the outline of a car seat. A staring boy emerging from a Tweety Bird piñata.

It is late July as San Francisco-based artist Julio César Morales leads me through the nearly completed installation of his career survey “OJO” at the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis. The paintings are from his 2010 series “Undocumented Interventions,” detailing how potential immigrants reach this country. “If you can’t afford to pay someone to walk you through the desert, you get sewn into a car seat, a dashboard, piñatas and so on,” Morales tells me.

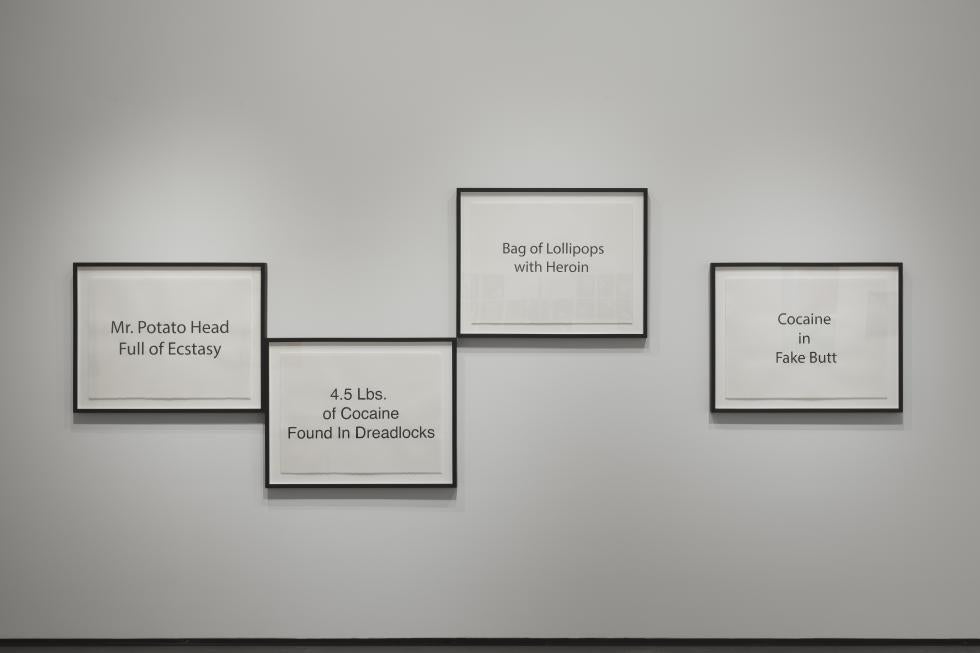

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ Narco Headline Series,

2015, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San

Francisco. Photo courtesy of the Manetti Shrem Museum © Muzi Li

Rowe.

These images are culled from the artist’s memories, what he witnessed growing up in Tijuana and just across the border in San Ysidro. “We lived as close as you can to the border in Tijuana. All the houses were pushed to the actual border wall,” Morales says. “When I was younger, we would cross almost on a daily basis. Of course, it was much easier back then.”

He points to a nearby piece showing a small boy’s legs poking out of a SpongeBob toy. “These are basically how people are reuniting families, or they attempt to do that.” Morales usually has a slight smile on his oval face, and it widens as he considers the macabre absurdities he is depicting. “They’re funny. A lot of this work is humorous because the truth really is stranger than fiction.”

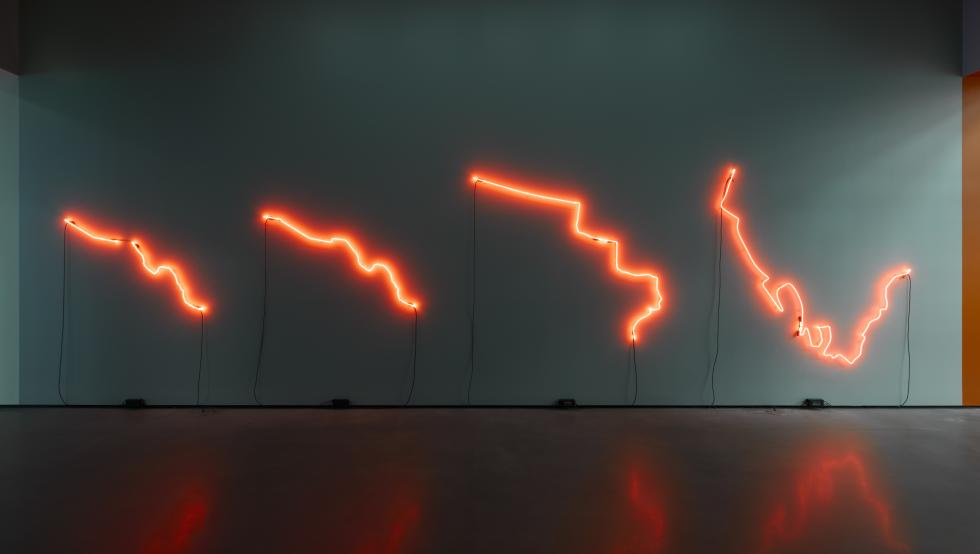

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ Line Cutters, #1-9, 2019.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

Photo courtesy of the Manetti Shrem Museum © Muzi Li Rowe.

Morales works in a variety of formats using photography, video, prints, painting and found objects, telling complex layered stories of human experience traversing the Mexico and United States border. The Manetti Shrem Museum exhibition opened in August and will be on view until Nov. 29. There are more than 50 works shown in four spaces spanning the last 15 years, including 10 new, never-before-exhibited pieces.

Morales began studying graphic design — including calligraphy, which he loves — at a community college in Chula Vista. Then he was seduced by photography. “I saw a Roy DeCarava exhibition — his street photography blew me away in his collaboration with Langston Hughes, ‘The Sweet Flypaper of Life.’ Hughes wrote texts and poetry, and Roy took photographs. It was a beautiful book.” The melding of text and image made a lasting influence.

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ OJO: Los Extranjeros,

2025 (left) and OJO: Los Extranjeros (El Paso 1938), 2025.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

Photo courtesy of the Manetti Shrem Museum © Muzi Li Rowe.

After graduating from the San Francisco Art Institute, Morales worked as an educator, artist and curator. His work has been exhibited and collected around the world. For the last decade, he was a senior museum curator in Arizona, but he has returned to San Francisco to concentrate on his studio practice.

Flanking the Manetti Shrem entrance, Morales’ neon sculpture “tomorrow is for those who can hear it coming,” commissioned by the museum, beams promisingly. The typography, a variation on the classic Old English font favored by OG cholos, also appears on gallery walls as song lyric excerpts. “Y nada, nos separaría, seremos nosotros, un día nada más. And nothing will tear us apart, we will be us, just for one day.”

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ Undocumented

Interventions series, 2010-2011. Courtesy of the artist and

Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco. Photo courtesy of the

Manetti Shrem Museum © Muzi Li Rowe.

“I feel like I’m a musician, but my instrument is visual art,” Morales says. “There’s a lot of elements of rhythm and melody, breakdowns, bridge — these terms that you hear or you see in music. I apply them to visual art.” Morales worked with Manetti Shrem Museum designer Hector Valdivia creating the exhibition spaces based around rhythm. “OJO” has an accompanying playlist Morales curated, which can be accessed by a QR code. The eclectic mix of musicians includes Ana Tijoux, Bad Bunny, Grace Jones, Nortec Collective, Juan Cirerol, Manu Chao, David Bowie, Nicola Cruz and King Tubby.

“Being at the border and being between two cultures, it’s not odd to listen to norteño music and at the same time listen to punk rock music or electronic music,” Morales says. For his companion show “My America” at Gallery Wendi Norris in San Francisco, he created an immersive sound experience with frequent collaborator Mexican Institute of Sound. They remixed the MIS song “My America Is Not Your America” into a meditative ambient soundtrack, which is listened to in a small booth fitting two people. There are also eight new watercolors from the “Gemelos” series, an extension of “Undocumented Interventions” depicting the subjects (twins) confined in unseen containers. The work is up until Nov. 1.

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ Las Líneas, 2028, 2022,

1845, and 1640, 2022, graphite on watercolor paper. Courtesy of

the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco. Photo

courtesy of the Manetti Shrem Museum © Muzi Li Rowe.

Morales points to the background of a 1938 Dorothea Lange photograph of a Mexican woman crossing into El Paso from Juárez, Mexico. “I was struck by the sign here, ‘Ojo Los Extranjeros,’” Morales says. “Los extranjeros are the strangers, the foreigners. In Spanish, ‘ojo’ is like ‘be vigilant,’ and at the same time ‘pay attention,’ so it has multiple meanings.” He collaborated with a vintage sign painter to recreate the cautionary instruction on a 16 1/2 x 30-inch wood panel that greets visitors. “This is your introduction to the exhibition,” Morales says.

Morales’ deconstructs cultural dynamics and tensions, often playfully, sometimes with clinical precision. His perspective can be intimate or global. The new graphite drawing “My America is Not Your America” shows a pale, upright human hand with the American continents bleeding out over the palm and wrist. “Las Líneas, 2028, 2022, 1846, and 1640,” a neon sculpture from 2022, consists of four panels, each holding bright magenta neon representations of the U.S.–Mexico border line at different historical moments.

Installation view, Julio César Morales’ My America is Not Your

America, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris,

San Francisco. Photo courtesy of the Manetti Shrem Museum © Hung

Q. Pham.

He leads me into the next gallery, which holds his 2009 series “Narquitecos.” The title is a combination of “narco” and “architect,” based on the idea of drug smugglers hiring architects to design tunnels. “It was a myth for such a long time until they discovered the first one,” Morales says.

Essentially a multimedia story about the tunnels between Mexico and the United States, “Narquitecos” includes a silk screen on canvas of a newspaper front page, drawings of the tunnels and a scale model of the physical product. Morales spent several summers in Tijuana with his cousins digging a tunnel for his godfather behind their grandparents’ house. “We weren’t sure why we were digging a tunnel. In exchange he would take us to see lucha libre wrestling matches,” Morales says. “I remember it. I still smell the dirt.”

When I returned to see the fully installed show, the museum’s founding director and show curator, Rachel Teagle, joined me. Teagle first encountered Morales’ work 25 years ago in San Diego. She eventually gave him his first museum show. “Julio, I believe, really wants his work to come across as hopeful — that we have the ability and authority to change the future, but we have to understand our past to be able to do that,” Teagle says. She asks me to watch Morales’ new video works, which weren’t running when I visited earlier.

Julio César Morales, Undocumented Interventions #17,

2010.Watercolor and ink on paper, 14 x 11 in. Courtesy of the

artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco. © Julio César

Morales.

On the opposite wall, three videos representing alternative views of border crossings called “We Don’t See” tell poetic stories of ill-fated immigrants and disaffected border guards. “The complexity of this dialogue across these two installations is a huge driveable force of the show,” Teagle says.

Morales hopes people have a visceral response to his work — to “feel” it, but also think about it and enjoy it.

“It’s like having a rhythm, having the work speak to you, having the work perform for you,” Morales says. “A specific type of tone or a specific type of rhythm, and then all of a sudden you realize what the content is. It really brings in a more internal reflection of the work.”

Editor’s note: This article was originally assigned by but not published in Alta Journal, which gave writer Marcus Crowder permission to submit it to Comstock’s.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Sacramento’s Latino Organizations Celebrate Día de los Muertos Against a Season of Cancellations

Latino Center of Arts & Culture expands El Panteón to more than 90 altars

Some organizations are canceling or scaling back events in response to community safety concerns, but others are going bigger than ever.

Art Exposed: Muzi Li Rowe

This mixed media artist and photographer explores culture through defunct technology

Whether it’s layers of tiny microchips or rows of dead batteries, each work in Muzi Li Rowe’s Magical Thinking series is like peering into a tiny museum where the most microscopic parts of now-defunct personal technology devices, from old Nokia flip phones to disposable cameras, become individual hallmarks of consumer culture.

Art Exposed: Manuel Fernando Rios

A West Sacramento Chicano artist confronts ethnic identity in his work

Mentored by Ricardo Favela of the Royal Chicano Air Force artist collective, Manuel Fernando Rios describes his artwork as “neo-Expressionist, neo-Chicano, mixed in with pop culture.” His solo show scheduled for May has been postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic, but he is continuing to make new work.

Art Exposed: Estella Sanchez

It’s been 12 years since Estella Sanchez signed rent papers on the first Sol Collective Arts and Cultural Center in Del Paso Heights. More than a decade, hundreds of art exhibitions and thousands of community events later, Sol Collective recently purchased the building on 21st Street in Sacramento. We sat down with Sanchez to talk art, activism, the importance of building ownership and snacks.

Art Exposed: Vincent Pacheco

A graphic artist blurs art and design and plays with the cultural language of piñatas

The artist builds piñatas in various forms of cultural artifacts. Each is a temporary monument to family, identity and cultural heritage.