One metaphor for carrying the worries and strife of the pandemic, according to artist Summer Ventis, is a held breath. With her recent exhibition “Heavier Than Air,” Ventis encouraged viewers to externalize their held breaths by inflating a balloon. As they contributed their own breath, they were invited to reflect on grief, loss, the weight of the pandemic era and the preciousness of being able to breathe freely.

An intimate and personal show, “Heavier Than Air” ran from Feb. 16 to March 22, 2022 at the Faith J. McKinnie Gallery. The show, curated by artist and placemaker Genesis “The Mayor” Torres, was installed in a room across from the front entrance to FJMG. This space, named “The Shadowbox,” sat in the shadow of FJMG’s cavernous main gallery and served as a space for invited artists to experiment and innovate in an illuminating public forum.

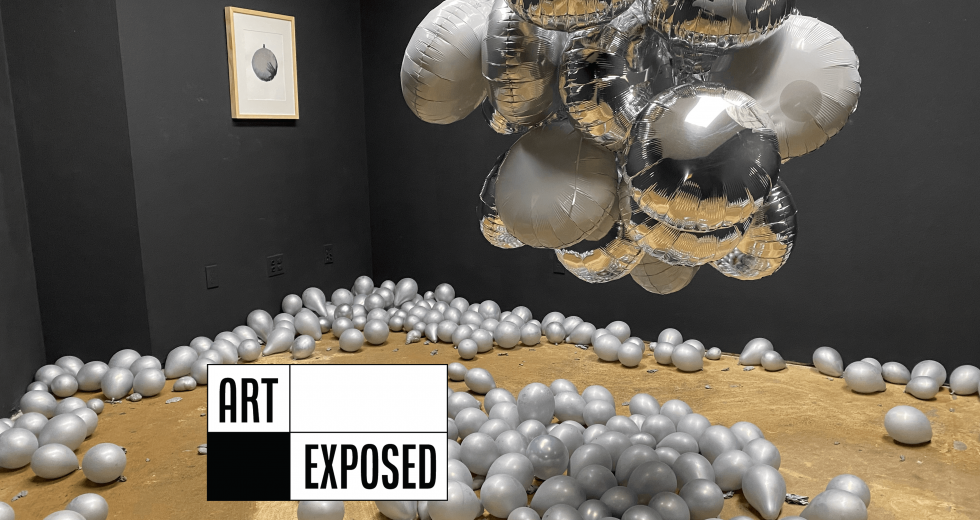

Inside the arresting, all-black setting of “The Shadowbox” hung a bundle of 29 silver, mylar balloons — all gently ebbing as visitors moved through the installation. The lung-like cluster titled “29 Held Breaths” was accompanied by numerous small crepe paper packets, cradling uninflated balloons, that lined the soot-black walls. These were punctuated by prints of balloons in various states of inflation. Introductory wall text greeted viewers at the door and encouraged them to take a packet and contribute a “breath.”

Having settled in Sacramento in 2017, after spending time in Ashland, Oregon and Iowa City, Iowa, Ventis serves as an Assistant Professor in the Art Department at California State University, Sacramento. In between preparing for a solo show at Axis Gallery in May and an upcoming contribution to the “Book It” exhibition opening at the Kondos Gallery at Sacramento City College, Ventis shares her thoughts below on “29 Breaths,” how the work relates to the rest of her practice, and how she interrogates the connections between people and their surroundings.

Let’s start with “29 Held Breaths.” It’s an incredibly powerful work that has a component of viewer participation. Where did this body of work stem from, how has it evolved over its various presentations and how do you envision the role of the viewer within it?

Between March 13th, 2020 and the first day “Heavier Than Air,” my show in “The Shadowbox,” was open to the public, 705 days had passed, almost two years. During that time, we all felt the weight of grief in some way, the heaviness of existence in these ever-changing times. I wanted to give others space to externalize their own held breaths.

The work started with my very personal and specific experience of the pandemic. Digging into that experience and trying to process it through the work made me feel the importance of each of us externalizing and processing our own specific experiences during this time, to share the weight of those experiences through seeing and feeling seen.

One of the components of the piece that struck me the most was how it explores the ways people and environments are changed by contact with each other. Was there a particular moment in your practice where this became a focal point for your work or is it something you’ve always been interested in?

As Lucy Lippard puts it in “On the Beaten Track,” “Nothing is more surrealist than tourism. Tourist and toured meet in unlikely combinations … to create a reality that is real to neither one.” As a result, I come to every encounter with a new place or a new person with the knowledge that no encounter can be “authentic” and the hope that, discarding the idea of authenticity, we can create new meaning together through our interactions.

Can you unpack the role of landscape a bit? Why is it so important for your work and how does it perform different functions in bodies of work like “Wilderness Reflections,” 2019-2020, and “a belly full of water against the future drought,” 2018?

Landscape is the intersection of our surroundings with the interpretation of those surroundings. Even the most faithfully representational landscape painting or photograph is this; the artist chooses the window through which they look at the space, the specific rectangle that they choose to frame. This framing necessarily highlights some things and excludes others. The space dictates the possible things that can be framed, but the artist chooses the framing.

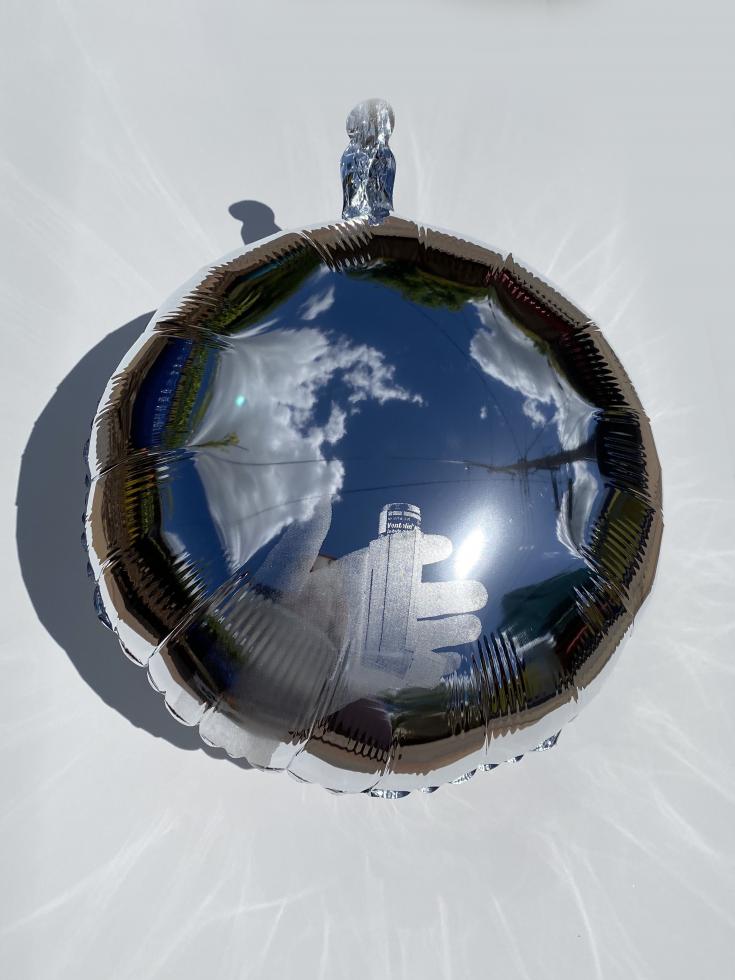

In my work, I try to bring awareness to that act of framing; I think about the ways in which my own subjectivity shapes what I choose to present, and I try to invite viewers to consider these questions for themselves. In “Wilderness Reflections,” for example, a reflective mylar tent form inhabits different spaces. If a viewer imagines or inserts themself inside the tent form, they realize that, while they can see their surroundings, most of what they can see is their own reflection. “a belly full of water against the future drought” considers ideas around boundaries and self-containment in the landscape in a different way. A cactus can remain self-sufficient or a balloon can hold air for a certain amount of time, but eventually they are both permeable to and dependent upon their surroundings.

Looking at both “Wilderness Reflections” and “a belly full in relation to 29 Held Breaths,” mylar and balloons are a throughline materially. How did you come to work with these materials and why do they make sense as a vehicle for the content of your work?

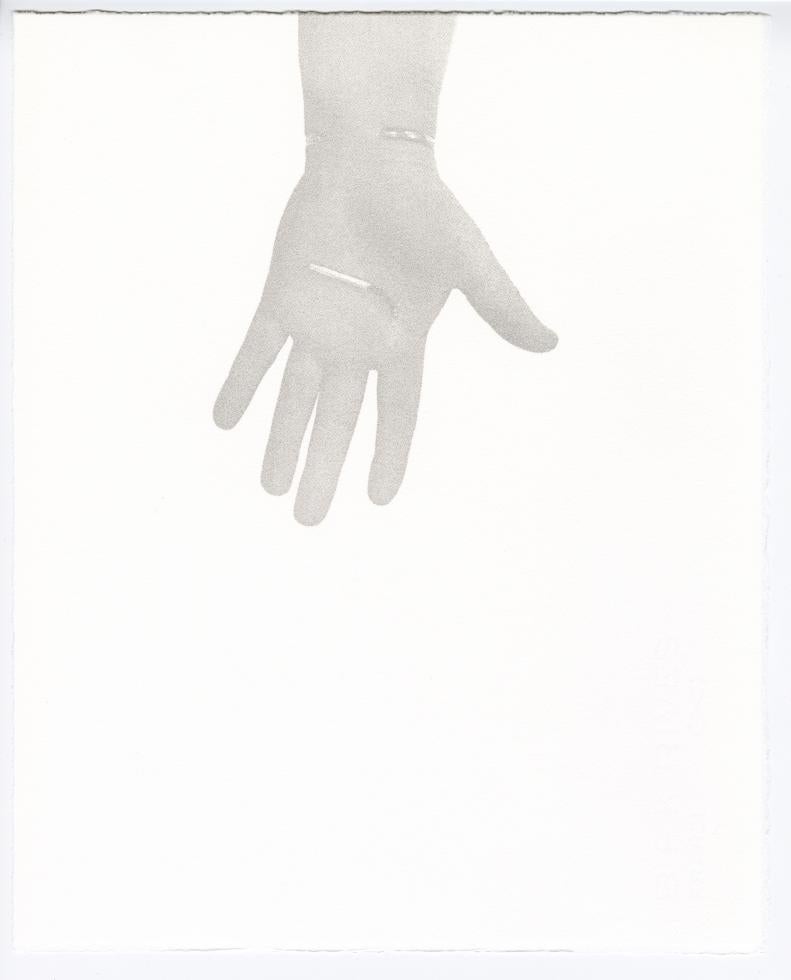

Reflective mylar and balloons are both permeable membranes, materials that can bring us outside of ourselves by making us aware of those selves. In a reflective surface, you see yourself, but also everything that surrounds you, and in that mirror-surface, everything is reversed. Blowing up a balloon puts something that was inside your body outside of your body in a tangible form that you can hold. Both materials allow us to see something about ourselves and our surroundings through reversal, making those things simultaneously familiar and strange.

In works like “Wilderness Reflections” and “Fringe Landscapes: Searching for a Better Grassland,” you have created these tent-like structures that are both sculptures themselves and vessels onto which you project or print images or forms. Conceptually, are these objects referencing the idea of shelter and the logical connection to the environment, or are they primarily support structures to emphasize how we as humans project ourselves onto the environment?

Yes! A tent is the thing we use to get out into the landscape, and also the thing that we use to separate and protect ourselves from the landscape.

Talking to a printmaker, I would be remiss not to bring up your relationship to paper. In your artist statement, you write that “paper becomes the “border-line surface,” the membrane that divides and connects what is inside us and what is outside.” How do you see paper operating as a membrane?

That “border-line surface” comes from a line in Gaston Bachelard’s “The Poetics of Space:” “Outside and inside are both intimate — they are always ready to be reversed. … If there exists a border-line surface between such an inside and outside, this surface is painful on both sides.”

There are a lot of different ways to define printmaking, but for me, a print is first and foremost the act of something touching something else and leaving a mark. The paper or other substrate is the site of this contact. The printed surface is the documentation of that act of touch.

In that traditional rectangular landscape image I mentioned earlier, the paper becomes the window between what is inside and what is outside, the site where the act of framing happens and is made visible.

Collaboration is also a key aspect of your practice. What about working with others and creating artwork together appeals to you?

Being that you are a professor in the art department at Sacramento State, do you think your work as an educator feeds into your collaborative nature?

Absolutely. The joy of seeing how everyone’s individual strengths and interests come together to create new meaning through conversation in the classroom has certainly been a part of what has motivated me to seek that out more in my own artistic practice.

Lastly, do you think you would be making work that was entirely different if you weren’t living and working in the City of Trees? Do you think this environment has had a measurable influence on your work?

In addition to making work about human-influenced environmental phenomena that are specific to this area, Sacramento is the most densely populated place where I have lived. Being in an urban environment has naturally caused my work to focus more on our interactions with each other and the ways they affect the spaces we inhabit.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Unity Lewis

A curator, artist and musician carries the legacy of his grandmother’s groundbreaking work documenting the Black experience

Unity Lewis recently curated a series at Crocker Art Museum that brought his grandmother’s book into the three-dimensional world by pairing works of artists from previous generations with their modern counterparts who will carry the torch.

Art Exposed: Vincent Pacheco

A graphic artist blurs art and design and plays with the cultural language of piñatas

The artist builds piñatas in various forms of cultural artifacts. Each is a temporary monument to family, identity and cultural heritage.

Art Exposed: Alina Tyulyu

A lifestyle photographer becomes a war documentarian when she returns to Ukraine as a volunteer

The Sacramento-based photographer is traveling around her

native country of Ukraine to aid refugees during the

Russia-Ukraine war, documenting their experiences along the

way.

Art Exposed: Nancy Sayavong

The Roseville-based sculptor uses woodworking techniques for both art and remodeling

As a woodworker and metal fabricator, Nancy Sayavong uses her

training both for art and remodeling jobs. Her work is

interested in the contrast between the romantic ideal of the

home and its lived reality.

Art Exposed: Tasha Reneé

The local potter on the hazards of ceramics and making peace with impermanence

Tasha Reneé sells ceramics independently and through plant shops

and home decor businesses and is currently pivoting to teach

others through private lessons, workshops and classes.

Art Exposed: Jonathan Joiner

How a filmmaker and creative director mines the past for inspiration to create fantastical objects, stop-motion video and playful GIFs

Jonathan Joiner finds inspiration in retro-futuristic gadgets,

movies and “practical things.”