The wood batons spin so fast they look like plane propellers. The rattan sticks have a snapping, cracking cadence as they collide in the air and against the combattants’ padded armor.

There is a graceful fierceness to everything about eskrima, a Filipino martial art also known as arnis and kali. And that is exactly what’s on display on a warm fall night in an unassuming structure off Folsom Boulevard.

The vigorous duels are erupting inside a dojo called the Rancho Cordova Martial Arts Center. As the slamming sounds get louder, the dojo’s founder, Mike McKenzie Sr., looks on from a back corner of the room. McKenzie is a fourth degree black belt in Multi-Style Doce Pares, a fluid, rapid-fire iteration of eskrima. His center also specializes in teaching Yaw-Yan, alternatively referred to as Filipino kickboxing.

Better known as “Master Mike,” McKenzie is a proud Filipino American who can remember a time when elements of the culture passed down through his family were barely seen or talked about in the greater Capital Region. Today, Sacramento County has a large Filipino population concentrated in enclaves like Elk Grove, where more than 27 percent of the population identifies as Filipino. When McKenzie was young, the most exciting things he heard about his grandparents’ original home involved a powerful martial art that was born, in part, out of a struggle for freedom from Spanish colonial forces in the West Pacific.

“When I was a teenager, there weren’t very many Filipino people in Sacramento, but when my grandmother’s brothers would come from the Philippines, they would always tell me about this arnis — or eskrima — martial art, and how a master of it can kill you, and you can’t touch him, and all these stories,” McKenzie recalls. “It was intriguing. I started looking for Filipino martial arts, but I wasn’t able to find that in Sacramento.”

But all that changed for McKenzie in the wake of a master eskrima practitioner from the Philippines making an appearance in West Sacramento. His visit started McKenzie down a path that he’s still on today, which includes training regional, state, national and world champions in Doce Pares and Yaw-Yan. But McKenzie and his instructors are all quick to point out that the gold-plated champion belts on their wall are not the most important aspect of the welcoming community they’ve created.

“What I enjoy most is making people familiar with this part of the Filipino culture,” McKenzie stresses. “I still go to the Philippines every single year to train with the masters of Doce Pares. In this gym, as much as any place in the United States, you can learn as close to the root of the tree as possible.”

Related: Dedication, Dance and Violence: Meet the Sacramento State student who moved from India to study mixed martial arts with Urijah Faber

History of resistance

McKenzie’s grandfather, Lucio Rabe, immigrated to the U.S. in the late 1920s. He had worked his way through college at the University of Southern California when Japanese imperial forces invaded the Philippines in 1942. The U.S. had already declared war on Japan, and Rabe started trying to enlist in the American army. At first, he was getting turned down because he wasn’t a U.S. citizen. (At the time, the Philippines was a U.S. territory, and Filipinos were considered non-citizen U.S. nationals.)

“He was persistent and kept going back to the recruiter, and he was finally told, ‘Come back next week when we start the draft,’” McKenzie explains. “Once my grandfather went through basic training, they found out he had a college degree, so they sent him to officer candidate school.”

Rabe was eventually shipped out to fight Japanese soldiers in New Guinea. Later, after Japan’s leadership surrendered, Rabe’s unit was sent to the Philippines. There, in 1945, he met his future wife, Josefina.

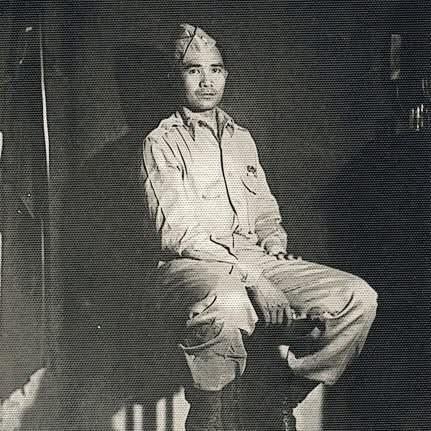

Lucio Rabe was a Filipino immigrant to Sacramento who fought for

the U.S. Army during World War II, and whose grandson, Mike

McKenzie is the founder of one of the main schools teaching

Eskrima in the Capital Region today. (Courtesy photograph)

In some ways, Rabe’s martial spirit reflects the same Filipino resolve that Eskrima partly evolved from: According to Grand Master Richardson C. Gialogo of the Philippine Eskrima Kali Arnis Federation, Indigenous Filipino warriors used an early version of eskrima to defeat Spanish colonial invaders in 1521 at the Battle of Mactan. They further refined their fighting art 43 years later when Spaniards returned for more conflict.

After the war, McKenzie’s grandparents moved to Stockton for a time before putting down roots in Sacramento in 1966. McKenzie was born in French Camp in 1968, and he and his mother joined her parents in Sacramento the following year.

In 1981, eskrima started to gain a reputation in Northern California when a Sacramento man named Al Conception, who was an eskrimador himself, sponsored several exciting practitioners from the Philippines to come over — Cacoy Cañete, Bonafacio “Loloy” Uy and Arnulfo “Dong” Cuesta — who then went on a tour across the U.S. as they showcased the martial art. Cacoy Cañete was already a grand master when he arrived. Uy and Cuesta would eventually earn the same distinction.

Related: Neighborhood Favorite: Kehaulani’s Cafe — French technique meets Hawaiian and Filipino comfort food

Nevertheless, McKenzie was still having trouble finding a place to train as a teen. While his grand-uncles had first sparked an interest in eskrima, he wasn’t able to immerse himself in it until the grandmaster Dionisio “Diony” Cañete held a seminar in West Sacramento in the late ‘90s. Dionisio Cañete had started coming out to California from Cebu City in the Philippines two decades earlier. After McKenzie went to the seminar, he was able to start learning from a couple of Dionisio Cañete’s well-trained students.

Years later, in 2006, McKenzie started teaching classes at the Magellan Hall in Rancho Cordova, an American Legion post known as Filipino Veterans Hall. That’s where he fostered his first class of competitors who started winning eskrima championships near and far.

Twelve years ago, McKenzie moved his operation into the Rancho Cordova Martial Arts Studio. He was eventually able to sponsor Remigio Berandoy, a seventh degree black belt in Doce Pares from Cebu City, to move to Rancho Cordova and become one of his instructors. He was also able to land Jordan Balcita as a teacher, a prime Yaw-Yan competitor from the Philippines.

As McKenzie was establishing Filipino martial arts in east Sacramento County, the sport was getting a shot in the arm in the southern part of the county, too. That was thanks to an eskrima champion from the Philippines named Master Jaunito “Nito” Noval starting to teach classes and train competitors there in the mid-2000s.

Lyle Pinlack is a Filipino martial artist who’s glad to see eskrima and Yaw-Yan flourishing around the City of Trees. He’s been training with McKenzie for 12 years, and for a good portion of that time so have his teenage sons, Ace and Mika. Pinlack enjoys having his boys connect with this part of their heritage alongside him.

“Master Mike” McKenzie holds pads as Yaw-Yan fighter Christina

Almeida practices a kick. (Photo by Scott Thomas Anderson)

“The reason I came here is that this is indigenous to the Philippines,” Pinlack points out. “It was created by Filipinos, for Filipinos, specifically. … With the Filipinos, it’s a very family friendly community. My boys have been training here for six years now, and they’ve competed. There’s no egos here. Everyone treats each other with respect. We all help each other out. And there’s always kindness. But you’ll never know that because of how deadly this martial art is, and how effective it is — you’d never know. It brings a sense of pride.”

Filipino martial artists from Sacramento explore and take on the world

Twelve days after a lively crowd showed up for the Bayanihan Festival in Elk Grove in October, a two-time Eskrima World Champion named Jeremy Mayberry-Antolin was inside the Rancho Cordova Martial Arts Center getting one of its fighters ready for a competition.

Antolin, who is half-Filipino, has been studying the culture’s martial arts for 26 years. He remembers a period when McKenzie’s Eskrimadors were traveling and competing in tournaments once a month. Eventually, when he was 16, Antolin was crowned a world champion while fighting in Cebu City in the Philippines in 2004. Later, he won that distinction again in 2018 while competing in Maui, Hawaii.

“The first time I won, I didn’t really know how to process it or register it,” Antolin remembers. “I think, strangely, it’s one of those things where the journey was more important than the destination. In hindsight, looking back, it’s always the road there where you have the most memories. The day of the competition — I don’t remember much from that day. But I remember a lot from all the training, and that’s what has stuck with me through the years.”

He adds, “I’m deeply passionate about sharing the art with others.”

One of the young Eskrimadors that Antolin is sharing his techniques with now is Charley Malagum. He’s been training in Doce Pares for three years and has just started to enter competitions. Malagum is currently prepping for an Eskrima tournament on Nov. 8 in San Luis Obispo.

Related: Fight On: MMA fighting is (another) full-time job

“I’m nervous and excited about the competition at the same time,” Malagum explains. “The thing I like about it is tracing back my roots as a Filipino American. I was born and raised here, so when I first learned about Filipino martial arts, I really wanted to dive deep into what my culture entails.”

Derlie Cabrera is another student at the center who’s considering getting into competitions. She focuses on Yaw-Yan. Cabrera trains three times a week and, in January, took a two-week trip to the Philippines to broaden her skill set.

“The trip to the Philippines was about getting more in-depth with Yaw-Yan,” she reflects. “I like the fact that we get to be more in touch with the culture, not only the fighting, but the food and the people. The hospitality is great. I felt like when we were there, it was more intense. We were trained by many teachers and coaches that came into Cebu from all around the Philippines.”

Christina Almeida has been training alongside Cabrera for the last two years. For her, the center is about bonding over a shared purpose.

“I like the environment because you see the same people all the time, and you kind of become like a family,” Almeida says. “It’s nice to have that environment and to be able to work with others that have that same interest as you. It’s more motivating.”

Cabrera and Almeida often train under Balcita, who first started learning Yaw-Yan when he was 13 in the Philippines. Balcita came to the U.S. in 2013 and has been a top-tier competitor ever since. He still fights in tournaments, though he says sustaining the culture that flows through the martial art is his main concern.

“I teach what I learned from my grandmaster back in the Philippines,” Balcita notes. “This is what I learned as a kid and I love sharing it. That’s what our grandmaster taught us. He said, ‘I’m teaching you this so someday you can share it.’”

–

Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Getting to Know: Dr. Robyn Magalit Rodriguez

A celebrated Asian American studies professor leaves the ivory tower for entrepreneurship

Encountering barriers in academia has prompted Dr. Robyn Magalit

Rodriguez to launch into entrepreneurship. She is leaving her

post as a full professor at UC Davis to create her own school,

farm and learning center.

Art Exposed: Julie Bernadeth Crumb

Weaving cultural memory and communal care into artistic practice

Whether creating elaborate jewelry inspired by pre-colonial harvest rituals, collaging woodcut prints into an altar homage to her Filipino homeland or sculpting clay into aquatic life forms for an underwater installation, award-winning multidisciplinary artist Julie Bernadeth Crumb uses her hands to forge materials into meditations on culture, identity and Indigeneity.

Neighborhood Favorite: Kehaulani’s Cafe

French technique meets Hawaiian and Filipino comfort food

At Kehaulani’s Cafe in Vallejo, the loco moco starts with short

ribs braised for 12 hours.

Emerging Leaders: Rosie Dauz

We honor 10 young professionals who have made a difference during the COVID-19 pandemic

Rosie Dauz was elected president of the Philippine National Day Association, an organization that works to empower and promote equity in the Filipino community, around the time COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.