California politics in the first years after Congress approved statehood on September 9, 1850, were ever-changing and confusing — and occasionally violent to a degree that’s hard to imagine. In fact, the single word which best describes those days would be implausible. The driving forces behind this unlikely story were the massive influx of young arrivals from the East seeking gold and glory in the foothills. There was a sudden need for laws and civil government as military authorities turned over the administration of California almost before the state government was ready.

In the first weeks of the war between the United States and Mexico, California was captured by U.S. forces, with only small skirmishes in the south continuing for another six months. The next three years saw the occupation of California by the U.S. military, with the governing of the territory led by a rapidly changing series of generals. During this time, news of the discovery of gold had reached the eastern states and young men started heading west by every route possible.

By the end of summer 1849, the continued federal occupation of California had become untenable. General Bennet C. Riley, California’s seventh military governor in less than three years, knew that the few soldiers under his control were simply not sufficient to maintain law and order. Having seen enough, Riley issued a proclamation calling for Californians to elect representatives, who would travel to Monterey to write a constitution defining the boundaries of California and creating a minimal framework for the formation of a permanent government.

(Illustration courtesy of California State Library)

The legislature that first convened at San Jose was unlike the modern institution we know today. In 1850, the average age of California’s lawmakers was 32 – 20 years younger than the legislators of today. Like the population of the state, most had come to California within the previous few months in pursuit of riches from the soil. Only two had been born in California while it was still part of the Spanish empire, and most of the rest were recent arrivals from the East Coast. Not counting the two native Californians, the farthest west birthplaces for the first lawmakers were Assemblymen John S. Bradford and William M. Shepherd from Illinois.

Stephen J. Field in 1890, when he was a Supreme Court Justice.

During his earlier career on the California Supreme Court, he had

a coat made with pockets large enough to carry a pistol in each.

(Public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons)

“Of the thirty-six members of which the Assembly then consisted, over two-thirds never made their appearance without having knives or pistols upon their persons, and frequently both. It was a thing of everyday occurrence for a member, when he entered the House, before taking his seat, to take off his pistols and lay them in the drawer of his desk. He did it with as little concern and as much a matter of course, as he took off his hat and hung it up.”

One notable figure was state Sen. Thomas J. Green of Sacramento, a traveler who never stayed put for long. California was his fourth legislature. Green donated some of his own books to be part of the new collection at what would grow into the California State Library and introduced a bill to establish and endow a state university. However, with California’s government facing significant financial challenges, Green’s bill was seen as a bit premature and didn’t pass. In fact, it would be another decade before the state would approve funding for a humble “normal school” for training teachers that would eventually become the California State University.

Not all the early bills were so forward thinking. Assemblyman Isaac S. K. Ogier of San Joaquin, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, introduced a bill to “prevent the immigration of free Negroes and persons of color into this state.” Ogier’s bill passed the Assembly with a strong majority but was killed the next day in the state Senate on a motion by Sen. David C. Broderick of San Francisco.

A photograph of David C. Broderick taken between 1855-1859.

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Broderick’s star continued to rise, and he was elected to the United States Senate in 1857. Given this national platform, Broderick continued along the lines of his earlier state Senate service, becoming a vocal member of the “Free Soilers” and strongly calling for an end to slavery. Broderick’s opposition to slavery brought him into conflict with David Terry, chief justice of the California Supreme Court, and after an exchange of harsh words, the two agreed to settle their differences in a pistol duel. Broderick was fatally injured in the exchange and died three days later.

Alexander P. Crittenden, right, with his daughters Laura

Crittenden Sanchez (left) and Ann Churchill Crittenden (second

from right) and Laura’s husband Ramon Sanchez. (Public domain

photo via Wikimedia Commons)

After the alleged suicide of state Sen. William D. Fair, who had served with Crittenden in the first legislature, Crittenden began an affair with his widow Laura. After nearly a decade-long entanglement between the two, Crittenden broke off his relationship with Laura Fair in favor of a renewed relationship with his wife. It was clearly not an amicable split, because Laura would soon after murder Crittenden in front of his wife and children.

The pace didn’t slow for more than a decade, and because there were far better opportunities to earn a living elsewhere, almost no legislators served more than a single term. By the end of the State of California’s first decade, more than 700 people had served in the legislature, approximately the same number that we’ve seen in the past 50.

It would be entirely reasonable to imagine that this sounds like an overly imaginative plot for a daytime drama. Indeed, to use a modern phrase, it would be entirely accurate to say that California politics “jumped the shark” during its first season and never looked back. We still do only rarely.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Sutter’s Fort Returns to Its Roots: Authenticity Wins Out Over Mythology

Schoolkids still find it a delight, even without living history characters

The Back Story: Sutter’s Fort, the 6-acre state park in Midtown Sacramento, is an underappreciated jewel in the crown of the region’s historic attractions.

Anna Judah: Far More Than Theodore Judah’s Victorian Housewife

Through her artistry, she brought the transcontinental railroad to life — before it was built

You wouldn’t know that a tragic love story led to the railroad that connected the East and West coasts for the first time.

The Violent, Bloody Folsom Prison Escape of 1903

New book details a dark time in the prison’s history

The prisoners made makeshift knives, or shivs, and used stolen razors during their siege. One prison guard died, and two were injured.

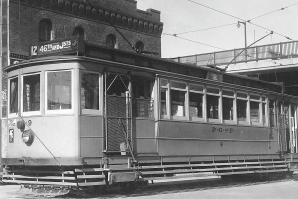

When Streetcars Roamed the Capital Region

The classic car system predated light rail by almost a century

While many of us believe that Sacramento’s light rail trains were innovative when they began tooting their way throughout the Capital Region in the 1980s, the current system is actually the reboot of a suburban trolley that slid, wended and awoke its way through the area many decades before.