Pete Oxenham, president of Roseville-based Fully Torqued Racing, has time to talk — but only on Sundays.

The rest of the week he’s busy keeping up with demand for the company’s custom parts for race cars and emerging transportation startups. He has five employees and desperately needs another programmer-operator for his high-tech Computer Numeric Control machines that turn out components. Because he’s had no luck finding someone, he says he’s working more than 100 hours a week to keep up.

He’s not alone; industries around the Capital Region are feeling the same pinch. In the last few years, industry and educators have stepped up efforts to attract more people to skilled trades and match them with training and apprenticeship programs. But it’s unclear if it will be enough to win over a culture that often looks down on blue-collar work and whether wage levels will be sufficient to draw big numbers to these jobs.

Inability to fill blue-collar, middle-skill jobs crimps the region’s economy. Recent reports by the California community college system’s local research arm put numbers to the shortage of specialists in manufacturing, construction, and maintenance and repair. In the Sacramento region, 80-90 percent of manufacturers report moderate to extreme difficulty hiring CNC operators and machinists. For auto service technicians, 900 jobs will open annually through at least 2022 in the 22-county region that includes Sacramento County. And the region faces a shortage of more than 7,000 construction workers a year through 2021.

Garner Products, a local manufacturer of data security equipment, makes its own parts to control quality. The shortage of CNC programmer-machinists means periodically outsourcing parts procurement, driving up product costs, says company Vice President Michelle Stofan.

Precision manufacturer Stewart Tool Company in Rancho Cordova is advertising out of state for pipe welders and CNC machinists. “It really makes me nervous,” says Quality Manager Amber Stewart. “A lot of the guys that we rely on every day are approaching retirement age within the next five years. They’re the leads of the department.” (Nationally, welders average 39 years old and machinists 47.)

For construction contractors, the lack of skilled tradespeople is obvious. Any position requiring three to five years of experience is tough to fill, says Kearston Vargas of Blue Mountain Enterprises in Vacaville, citing carpenters, painters, stucco specialists, HVAC techs, drywallers, plumbers and solar installers. “Really, it’s all of the skilled labor that we hire for that we struggle with,” she says.

REVIVING INDUSTRIAL ARTS

The erosion of high-school vocational-tech programs starting in the 1990s contributed to reducing the skills pipeline. Nationally, the percentage of students who earned course credits in construction and architecture, manufacturing, or repair and transportation fell from about 40 percent in 1990 to 28 percent in 2009, the latest year for which the government has data.

Some school districts are reviving the industrial arts. One example is the $14.5-million career technical education center under construction at Folsom High School, where students will learn manufacturing, engineering and architecture skills. Scheduled for completion in 2020, the 20,000-square-foot facility will feature six CNC machines, four lathes, four welding stations, a grinder, a floor mill and more. “We’re not aware of another high school that’s going to have a stand-alone facility dedicated to manufacturing,” says Angela Griffin Ankhelyi, community engagement specialist for Folsom Cordova Unified School District.

The center will support the district’s investments in new technical classes. In the 2018-19 school year, Folsom High launched the first of a two-course sequence in product innovation and design. And the district is planning a four-week summer internship program this month, says district Career Technical Education Coordinator Alicia Caddell.

Access to equipment can launch careers. When Oxenham was attending Rocklin High School, there was no formal CNC curriculum, but he had an instructor who knew his stuff and gave him seat time on a CNC machine. That kind of practice on a tool that costs into the five and six figures is rare. “On day one, kids can pop in a block of aluminum, hit a green button, and the machine revs up, starts moving it around, creating it, and making chips and all this noise, and then a part pops out,” Oxenham says. “And the kids are like, ‘Oh my God, I just made this. I can do this.’”

“It’s our responsibility as an industry to get our own workers and to compete with everybody else to make a case that we’re the best industry with the best kind of jobs.” Rick Larkey, executive director, North State Building Industry Foundation

Folsom Cordova and other districts also are coordinating with community colleges to create seamless career paths. Those who pass the second of Folsom High’s two product innovation courses will earn credit toward a degree in Sierra College’s advanced manufacturing program or in welding programs at two of the four Los Rios Community College District schools, says Caddell.

One Los Rios school, American River College, also is making dual enrollment efforts possible in a few other districts, offering high school students access to college-level career tech classes and credit toward certificates or degrees in automotive repair, diesel technology and the like. Students get a blueprint for turning the coursework into a career. “We constantly bring in people from industry who let them know if they continue on this path, there are amazing careers ahead of them,” says Frank Kobayashi, associate vice president of workforce development at ARC.

Oxenham, who is solicited for advice on regional school middle-skills initiatives, says it’s too soon to tell how successful efforts will be to market manufacturing careers to youth and their parents. “Right now, there’s not a pipeline of these people coming out because that shift hasn’t happened on the front end,” he says.

There’s one positive sign in the community college system. Starting in 2016, the state began putting $200 million to $250 million annually toward upgrading career technical education, and one goal is to boost by 20 percent by 2022 the number of students who receive training for high-demand jobs. For the Los Rios district, that’s meant new welding bays and better instructional labs, says Kobayashi. In blue-collar tech education, Los Rios almost has hit the enrollment goal; the number of students in their industrial technology programs is more than 5,000, a 19-percent increase in the last three years, according to the district.

INDUSTRY IN A HURRY

For all of that promise, area companies aren’t waiting around to see if educational investments make a dent.

In April 2018, Siemens Mobility, Tri Tool, Garner Products and other companies formed a leadership team to kick off the Sacramento Valley Manufacturing Initiative. By October, an SVMI workforce committee offered a six-week pre-apprenticeship boot camp on CNC machining that attracted 14 participants, most in their mid-30s. Instructors were provided by several companies, including Garner Products, the data security equipment manufacturer. The payoff was immediate: The company hired one of the course graduates in its machine shop who’s done an “awesome job,” says Stofan.

SVMI, which now has 35 member companies, also is on an outreach blitz that includes company visits to high schools, student tours of facilities, booths at community events and skills training for high-school industrial arts teachers. SVMI members are on high school and community college career tech-ed advisory committees, and SVMI Vice President Joe Wernette has advised the Folsom Cordova district on CNC machine purchases, says Caddell.

Residential construction’s skills crisis is a few years older, as are the industry’s efforts. The recession cut the workforce in the Sacramento metro region by 30,000 people from 2007 to 2011, and many left for good. The region’s dire shortage of housing makes it urgent to ramp back up. Because contractors were continually hiring away from one another, the Northstate Building Industry Foundation launched a campaign in 2016 to get 5,000 new residential construction workers on the job by 2021.

That led to a flurry of training and marketing activities. In the effort’s first year, participating companies provided 82 home-building internships to high school juniors and seniors, and four companies led 24 after-school workshops for students on the basics of building. That led to 1,200 new hires in the first year, the foundation calculates.

Part of that outreach has been geared toward rebranding construction as a career path. “These are really good jobs for somebody who doesn’t want to spend four years and go into massive debt,” says Vargas. The other part is convincing more companies to get on board with the effort. “It’s our responsibility as an industry to get our own workers and to compete with everybody else to make a case that we’re the best industry with the best kind of jobs,” says Rick Larkey, executive director of the Roseville-based North State Building Industry Foundation.

SKILLS GAP OR PAY GAP?

For all of that, there’s a knotty economic problem: how to boost wages enough to attract people to these fields while competing on price with companies in lower-cost areas and, sometimes, countries.

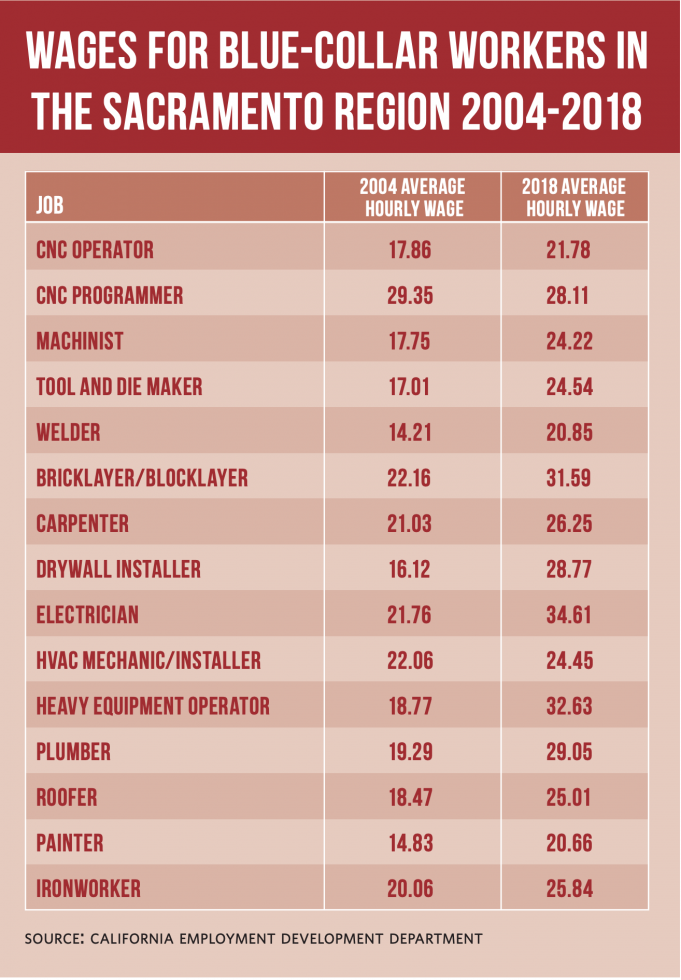

A few labor economists contend the blue-collar skills problem is in part a wage problem given that rates for many of the key occupations aren’t increasing significantly. According to California Employment Development Department data, from 2004 to 2018 average real wages in the four-county Sacramento metro area actually fell for CNC tool operators and CNC programmers. (An EDD spokesperson says figures for the CNC programmer category aren’t as reliable as others, given the small number of programmers available to survey. Also, the 2004 EDD data exclude Yolo County because of a 2006 change in the metro area’s definition.) Wages for welders, machinists and tool and die makers outpaced inflation. Earnings for all of these jobs were well above the living wage for a single adult but in most cases not enough for an adult with a child at home.

The numbers are similar for high-demand construction jobs. The data since 2004 show big gains in real earnings for drywall installers, electricians and heavy equipment operators — but losses for carpenters, HVAC mechanics and installers, and ironworkers. “Basic economics would imply that … when you say there’s a labor shortage, there’s actually a shortage at the wages you want to pay,” says Kevin Duncan, a labor economist at Colorado State University-Pueblo who’s been a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley’s Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

Some industry representatives agree there’s a wage problem. David Goodreau, chairman of the Small Manufacturers Association of California, calls himself a critic of what manufacturers pay. “I think given the technical and proficiency levels that people in manufacturing have to maintain, it doesn’t reflect the level of pay that they’re getting,” he says. “And that’s a problem we have as far as getting new kids into the industry.”

On the construction side, Michele Daugherty, president and CEO of the Northern California chapter of Associated Builders and Contractors, takes issue with the EDD numbers. Her members report “double-digit wage growth” in recent years, she says. Lower-end contractors could be dragging down the averages: The EDD data show the mean relative standard error — a measure of deviation from the average — is high for Sacramento-area construction occupations compared to other jobs.

And both Goodreau and Daugherty say paying workers more also means charging higher prices. Goodreau says that’s impossible for manufacturers, who are up against lower-wage competition out of state and internationally. In construction, Daugherty says higher wages also mean higher house prices in a state that’s in the middle of a supply crunch.

Labor researcher and management professor Peter Cappelli of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School has no words of comfort for manufacturers. “Those who study international trade would advise us not to produce goods that other countries can turn out more cheaply,” he writes by email, adding companies need to either raise productivity so that they can cut prices or come up with products tailored to a local market that outside companies can’t compete with.

Goodreau thinks companies can raise productivity by building a talent pipeline, much like pro baseball teams do when they invest in their minor-league systems. Manufacturers need to visit high schools to talk about manufacturing and take on apprentices and interns, exactly what SVMI is doing. Those recruits tend to stay at their companies long-term and become productive enough that firms can compete on price and quality even at higher wages, says Goodreau. Over the years, SMA and a partner organization have helped place about 450 young manufacturing interns. Between one quarter and one third ended up staying at their companies long term, beating the one of eight recruited through traditional advertising, he says.

That strategy shows the most promise for Sacramento industry leaders in navigating the squeeze between wages and sales price. Dean Peckam, executive director at SVMI, says setting aside time and money to recruit the next generation of skilled workers is tough for individual companies, given day-to-day business pressures. So the solution is to tackle the problem as an industry. “We need everybody to realize that — I know it sounds corny — but it’s a team effort. We just can’t complain about [the worker shortage] — we have to be proactive and engaged in our community.”

Comments

I teach Welding at Yuba College. We have also installed a new CNC HAAS Lab and upgraded our manual machine shop lab. We also have introduced a new certificate called "Fabrication and Manufacturing Methods," this is a one year certificate that builds on students welding skills or other skills that they may have. Like the title states, it focuses on fabrication methods. this means using fabrication equipment like the press brake, layout for sheet and structural applications, etc. It also incorporates Solidworks and Fusion 360 for CAD/CAM. It provides students with hands on experience in the Manual and CNC Machine shop. We are focusing on a student that has experience in many aspects of the metal working industry which provides them with opportunities in the industry. We like to use the terms Welder-machinist or Machinist-welder.