When winemaker Eric Hays met his wife, Emily Hays, more than 13 years ago in Sacramento, she owned a small shop, Wildflower Boutique, where she sold organic, fair trade and sustainable products. At the time, he worked for a winery in Placerville and wasn’t focused on the environmental impacts of conventional winemaking, but his wife immediately began teaching him about sustainability and the importance of treating the environment with respect.

In 2010, when Hays and his wife opened Chateau Davell in Camino, they built their winery on sustainable practices from day one. “We do it mostly because we live on the vineyard … and not wanting to be exposed to harsh chemicals. … Secondly, it’s to try (to) just respect the land and Mother Earth and not poison her,” Hays says.

In the heart of California’s wine country — Mendocino, Napa and Sonoma counties — it’s easy to find biodynamically farmed vineyards and organic-certified and vegan wines. But here in the Capital Region, there’s an emerging market among boutique vineyards and wineries focused on low-intervention farming and production methods that are cultivating a way of life rather than bolstering industry trends.

At Chateau Davell, six Southdown sheep — a small heritage breed — graze on unwanted vegetation and fertilize the 4-acre vineyard in Shingle Springs (there also is a half-acre vineyard in Camino), and cover crops (grasses and legumes) planted in the vineyard compete with weeds; control soil erosion; retain moisture; allow for nitrogen fixation; improve soil fertility; and attract biodiversity, like beneficial insects that control pests and disease.

For Hays, it’s important to extend a light footprint throughout the business. During production, he chooses not to filter or fine the wine, keeping it in its most natural state. Filtering and fining remove sediment and clarify the wine, but fining agents are commonly made from animal proteins, such as isinglass made from the air bladder of fish, albumin from egg whites or gelatin from bones, making them unsuitable for vegans.

Although vegan firming agents exist, Hays says, “It’s OK if a wine is a little bit cloudy. Filtering and fining can strip away the bouquet,” referring to the wine’s aroma. “Oftentimes, when folks come to our winery and they’re smelling our wines, they’re just blown away by how much bouquet our wines have.”

While Chateau Davell wines are vegan, they aren’t labeled or heavily marketed as such. In fact, vegan, organic and biodynamic wines are such a small segment of the U.S. market (experts estimate 1-2 percent), they don’t yet command mainstream analytics or occupy space on retail shelves.

At Clavey Vineyards & Winery in Nevada City, Josh Orman was making vegan wines before the family-run business became vegan-certified and began labeling them. “It came down to the style of winemaking I was doing,” Orman says. “I wasn’t trying to change everything in the winery or lab. … I’m doing it out in the field.”

But with several vegan family and friends, it made sense to Orman to market his organically farmed vegan wine, especially being located in a progressive region of Nevada County that caters to vegans.

“People are really starting to realize what they’re consuming and how their food products are being processed and made,” says Orman, who expanded his market to include local co-ops and health-conscious grocery stores. “They’re having a better understanding of what these larger wineries are really doing to their wine to make it taste the same year in and year out.”

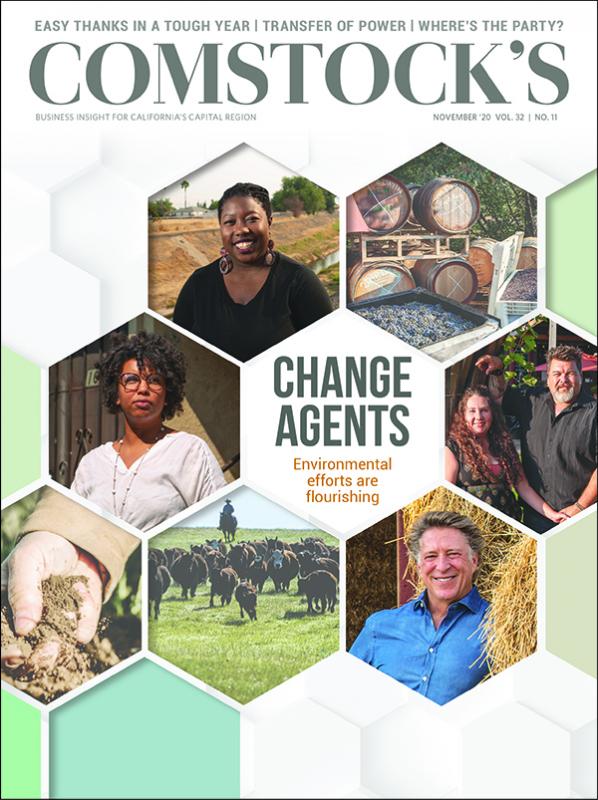

Emily (left) and Eric Hays opened Chateau Davell winery in 2010.

The couple has a 4-acre vineyard in Shingle Springs and a

half-acre vineyard in Camino, where the winery is located.

While Orman tries to harvest his grapes at similar sugar and acid levels each year, the nature of low-intervention production (minimal chemical or physical manipulation of the wine) always yields slight variations, “but that’s kind of what makes winemaking and wine so exciting and more enjoyable,” he says. “You can go wine tasting and try four wines from the same place, different years, and they’ll all taste just a bit different.”

In Sutter Creek, Shake Ridge Ranch, a 46-acre family-run vineyard on a steep hillside with rocky soil, uses “minimal and judicious intervention,” says owner Ann Kraemer, who continues to evolve her farming practices to work with the natural ecology of the land.

Kraemer used to control the vineyard’s weeds with a single application of Roundup, a better alternative, she thought, to mechanical weeding with tractors that use diesel and compact the soil, or hours of manual labor in the heat. But nearly four years ago, she began planting cover crops instead to do the work for her.

And for the last 10 years, she’s attracted more than 20 barn owl families to her vineyard by hanging owl boxes to replace chemical baiting and mechanical trapping of gophers that damage the vines.

“One owl family is supposed to be able to eat 1,000 gophers over the season,” Kraemer says. “It seems like anything we can do to work with nature and let nature be the driving force instead of deciding it’s got to do what we need it to do is a really good thing.”

“It seems like anything we can do to work with nature and let nature be the driving force instead of deciding it’s got to do what we need it to do is a really good thing.”

Ann Kraemer, owner, Shake Ridge Ranch

For more than three years, Shake Ridge Ranch has farmed entirely organic (though it is not certified due to the time restraints to undergo the process, Kraemer says), and its efforts are attracting buyers. Kraemer sells organically grown grapes to 34 winemakers, many of them emerging entrepreneurs in the Napa and Sonoma region. “They really want to be able to tell their consumers … what our farming practices are,” she says. “And they feel they need to now that their consumers are much more demanding.”

When Frank Hildebrand and his wife, Teena Hildebrand, moved to the foothills in 2000, they dreamed of planting a vineyard and opening a winery on raw land. But with two small children playing outdoors, he quickly realized he couldn’t use the chemicals and conventional farming methods he’d learned at UC Davis.

Chateau Davell wines are vegan, but aren’t marketed in that way.

“We started this back in 2001, when we first planted our vineyard, so there was no trend at all when we started,” says Hildebrand, owner of Narrow Gate Vineyards in Placerville. “So for us, it was a matter of stewarding our land and protecting our family.”

Hildebrand began farming organically and transitioned to biodynamic farming, which meets organic standards but requires more rigorous farming practices for environmental health and farm fertility. In 2010, Narrow Gate Vineyards became the only biodynamic farm in the Capital Region to be certified by the Demeter Association, the biodynamic certifying body in the U.S.

Biodynamic farming strives to create an ecosystem within a farm that ultimately will take care of itself, explains Evrett Lunquist, director of certification at the Demeter Association. That includes practices such as integrating livestock on the farm when possible to produce manure to create compost for soil fertility and designating a minimum of 10 percent of a farm’s land to attract biological diversity to attract beneficial insects and wildlife that promote a healthy food web and naturally control pest populations, explains Lunquist.

Demeter also evaluates irrigation and water-conservation practices, the level of microbial life in the soil, the use of cover crops, and animal welfare, some of modern agriculture’s greatest challenges. But some farmers struggle with what is perceived as the offbeat practices of biodynamics, such as ripening compost in a bovine’s horn buried in the earth before it’s applied to the soil as a spray.

When a Demeter-certified farmer sent his ripened horn manure to a microbiological testing laboratory, “the material came back off the charts,” says Lunquist. “There were so many microbes in that material … the lab had never seen anything so potent before.” Soil microbes are fundamental to soil health.

Hildebrand says it’s up to each farmer to figure out their own value in what they’re doing. His own passion inspires his team in the tasting room, and that translates into the sales the winery makes.

Before the pandemic, Hildebrand led tours of his farm for groups of 50-60 of his wine club members, introducing them to the fundamental principles of biodynamic farming.

“We have a tolerance to understand that nature’s nature. Whether the birds are stealing our grapes or whether there’s a deer on the property or whether (the vines) have mites or something,” says Hildebrand, “we have to allow (for) the community of nature to be involved, and we want that involvement. That’s what makes our soils unique, our land unique, our wine unique in the end.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Getting to Know: Julianna Boggs

Tabeaux Cellars co-owner on building a family-run winery in Amador County

The family behind Tabeaux Cellars is not of your standard wine-country lineage. Rather, they are “just a family producing a decidedly small allocation of foothill glou glou,” as the winery’s charming Instagram bio states.

Startup of the Month: Drinjk Wines

Wine business delivers single-serve bottles

There’s nothing worse than pouring wine down the drain, says Brett Bayda, so he created Drinjk Wines for consumers who want more portion control.

Revolution’s Evolution

Urban winery has become a hotspot for creative vegan cooking

The success of Revolution Winery & Kitchen is a testament to retooling where necessary and sticking with what works in order to grow and thrive in Sacramento’s food and drink landscape.

Fields of Gold

The Sacramento Valley’s climate is ripe for producing quality olive oil

Olive farmers in California are determined to become known as producers of high-quality olive oil, and much of that olive oil is being produced in the Mediterranean climate of the Sacramento Valley.